Indexed In

- JournalTOCs

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Review Article - (2023) Volume , Issue

Voting with Oneâs Feet or for Oneâs Future? Electoral Migration, Voter Vulnerability and the 2019 General Elections in Nigeria

Mike Omilusi*Received: 29-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. GJISS-22-19051; Editor assigned: 02-Dec-2022, Pre QC No. GJISS-22-19051 (PQ); Reviewed: 16-Dec-2022, QC No. GJISS-22-19051; Revised: 25-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. GJISS-22-19051 (R); Published: 31-Jan-2023

Abstract

Electoral politics in Nigeria is traditionally characterized by tension-soaked atmosphere, outbreaks of violence both “incidental” and “strategic” coupled with zero-sum political systems which are high stakes and confrontational in nature. In view of the fact that elections are often heralded by palpable insecurity and held amidst open brigandage throughout the electoral cycle, institutions of democracy in the country become battle grounds and face enormous political pressure as a prelude to election day contest. The buildup to the 2019 general elections justifies this submission as many of the risk factors that affected past elections remain unchanged. Given such a picture as history has repeatedly painted with grim outlines, there is thus, a pattern of internal and cross border migratory movements during elections in Nigeria the elites relocating their families abroad and other Nigerians seeking refuge in their communities. The overriding questions are: How does this pattern of electoral migration impact on voter turnout and legitimacy of the process? How has this potential threat to the realisation of peaceful and credible election elicited synergy among government, political parties, media and the civil society on possible negative consequences of insecurity and fear of uncertainty? Using secondary sources of data collection, this article therefore, seeks to explore the interplay of voter migratory movement and election security in Nigeria. It avers that unhindered meaningful participation of citizens in public affairs, which is a distinguishing feature of democratic societies, is key to democratic sustenance in Nigeria. This is meant to entrench a credible electoral process as the foundation for building democratic institutions, two decades after the emergence of civil rule.

Keywords

Election; Voting; Security vulnerability; Electoral migration; Violence

Introduction

Elections are intended to provide a peaceful method for groups to compete for political power, sometimes directly replacing violent alternatives. The overarching objective of citizens changing the outcome of an election is anchored on participation in a political space devoid of tension and violence given the fact that periodic elections have become a tool for democratic stability, accountability and ultimately, human development [1]. When people exercise their power as voters, it affords them the opportunity to elect responsive grassroots and national leaders who are reflective of the communities they serve. However, underlying tensions in a society and high-stake competition can also result in violent and fraudulent elections. In some developing democracies, as evidenced in Nigeria, where the absence of a level playing field for major actors or threats to lives and property tend to obstruct peaceful electioneering, voting with one’s feet becomes a common but painful alternative [2].

There has been relatively little research on the issue of elite and voter migratory movements which I refer to as electoral migration in this essay. Though some studies in other climes have explored the use of voter registration information as an alternative source of migration data, the current study seeks to unravel the propelling forces of migratory movements within states, geopolitical zones and local councils of Nigeria and outside the country during election season. The overriding questions are: How does this pattern of electoral migration impact on voter turn-out and legitimacy of the process? How has the potential threat to the realisation of peaceful and credible election merited synergy among government, political parties, media and civil society organisations on possible negative consequences of insecurity and fear of uncertainty? Beyond the search for economic opportunity and jobs which are the most commonly cited reasons for many Nigerians migrating abroad, this essay undertakes a theoretical excursion to explore the nexus between election security and migratory movements [3-6]. Using secondary sources of data collection, it avers that unhindered citizen participation will enhance the country’s projection of entrenching a credible electoral process as the foundation for building democratic institutions and consolidating genuinely democratic political systems.

Literature Review

A contextual overview of voter vulnerability and election security

Electoral politics brings into focus the hopes, dreams and even fears of the people as they seek leaders to shape the future. The quality of the elections is essential for the implementation of democracy; which means elections should be credible, transparent and regular. While elections alone are insufficient for democracy, they are nevertheless a prerequisite [7]. This is because they promote political participation and competition needed for democracy. In some instances too, elections can provoke migration of voters from one location to another.

Voter vulnerability simply connotes all potential and real dangers or irregularities around election period that may hinder voters from exercising their franchise or subject them to manipulation by other political actors. There are severe vulnerabilities that could be leveraged to manipulate voters, violate their rights, and subvert their choice in an election cycle particularly in developing countries [8].

Among the few drivers of electoral migration are two major ones that propel people to move: When they are unable to vote where they reside and the fear of uncertainty. Factors that generate vulnerability may cause a prospective voter to leave a city of residence for another place considered to be less volatile particularly in a country where elections are conducted in a warlike manner [9]. Vulnerability in this context should therefore, be understood as both situational and personal because not all potential voters in a situation of insecurity relocate.

Generally, security is critical in the protection of electoral personnel, locations and processes. It is significant in creating the proper environment for electoral staff to carry out their duties; for voters to freely and safely go to their polling units to vote; for candidates and political parties to organize rallies and campaigns; and for other numerous stakeholders to discharge their responsibilities. Election security, in its purist sense, refers to anything that interferes with the ability of a citizen to vote and for their vote to be properly recorded and reported back [10]. Put differently, election security denotes protection for every individual involved in the electoral process and includes Electoral Management Body (EMB) and its officials, EMB ad-hoc staff, party representatives, the electorate (voters), election monitors and observers, media agents, security officials and other individuals/groups incidental to the smooth running of the elections. In extreme and desperate cases, the security breaches are meant to ensure elections do not hold. The stakes are high when it comes to election security, be it in terms of ballot box snatching and stuffing, destruction of ballot materials, scaring away voters, vote buying and bribery or as grave as hijacking of electoral personnel and materials to unknown location to temper with electoral outcomes [11].

Background to the 2019 elections

Nigeria has enjoyed its longest-ever stretch of uninterrupted civilian rule having conducted six elections since 1999 when the country broke with military rule. All the elections were tainted by controversy and violence with varying degrees. Interestingly, the 2015 general elections facilitated Nigeria’s first democratic transfer of presidential power between candidates of opposing political parties. Analysts described it as a closely fought contest among Nigeria’s ‘political gladiators’. This progress has been greatly enabled by the active participation of civil society groups assisting with voter registration and maintaining parallel vote counts [12]. The election, after all, was historic and regarded as a breakthrough given the fact that citizens insisted their votes should count. Expectedly therefore, the country is to improve on this relatively appreciable feat with coordinated synergy among the stakeholders bearing in mind the strategic position of Nigeria to the West Africa sub-region in particular and Africa as a whole [13].

At stake in Nigeria's election is a vibrant country of some 190 million people, including more than 84 million registered voters an increase of 18 percent from the 2015 election-that is Africa's largest economy and oil producer. The 2019 presidential and parliamentary votes took place under the shadow of a devastating war against Islamist militants in the Northeast, banditry in the Northwest and oil militants in the South and deadly fighting in the central region between farmers and herders over increasingly precious land keep security forces stretched and the population on edge. Civil society, research and other organisations identified risks of violence in most of the country’s 36 states. The executive arm, as posited by Dele-Adedeji, still maintains certain authoritarian characteristics that are reminiscent of the military era. One of these is the use of the armed forces to manipulate election processes. For the electoral umpire, although applauded for organizing broadly credible elections in 2015, public confidence in the electoral body is mixed. There are widespread concerns about the INEC’s ability to oversee and administer free and fair elections [14]. For political gladiators accustomed to electoral platforms that accommodate greater communal tension and violence occasioned by desperation and spread of disinformation, electoral migration in such circumstances becomes a significant part of the electoral cycle.

Today, it is widely understood that the ultimate guarantor of social peace is robust democratic institutions such as elections. Unfortunately, lack of tolerance, the undemocratic attitude of the Nigeria security agents, wrong use of instrument of coercion and suppression, use of power for personal affluence and influence, recourse to primordial identities, are regular facilitators of tensions in the country around election period. Election is generally perceived by politicians as a mean to power given the urge to win-at-all cost and the huge democratic governance deficits that pervade the country [15]. In view of the fact that political office holders in Nigeria are among the best-paid in the world not to mention the possibility of illicit gains from oil-fueled corruption, the level of desperation among political gladiators may not provoke any surprise, but more tension in an electoral contest. Overall, the campaign issues were similar to those that featured in the 2015 presidential elections and the political atmosphere relatively the same except for the level of desperation among politicians that was further heightened. While this has received increased scholarly attention, little is known of election-induced migration in the country.

Patterns of electoral migration in Nigeria

In a country where power and state resources are often exploited for personal use by office holders, the stakes are always dangerously higher. Tensions arising from such process as evidenced during elections in Nigeria usually precipitate temporary migration of citizens. Studies of elections in the country suggest that such migration is largely driven by anxieties about electoral security and uncertain future on the one hand and resolution to exercise franchise where electors registered. The hydra-headed issues bedeviling Nigeria’s elections always feature even after all stakeholders declare their readiness to ensure the elections are hitch-free [16]. In the build-up to the elections, there were an increasing number of rallies, protests and demonstrations particularly in Abuja and other states. In this essay, I highlight five specific patterns of electoral migration around election period as established in the 2019 general elections.

Geopolitical/ethnic migration: There has been a long-held belief that elections in Nigeria come with the threat of violence which causes some voters to stay at home or relocate to their communities for safety. Regional and identity politics are important factors in Nigeria’s election. Nigeria’s regular incidences of violence, most of which seem to flare up after an election, do have something to do with how Nigerians see the issue of citizenship. According to some analysts, contemporary armed conflicts are more frequently being fought along primordial sentiments and no longer follow ideological or class affiliations. Also, identity politics, guided by ethnicity, religion and provenance, are usually pivotal in Nigerian elections. A rapid escalation of violence is usually facilitated by local social networks nurtured by ethno-religious grievances. In the early weeks of 2019, concerns over the presidential election were heightened as many Southerners living in core Northern states and Abuja were said to have concluded plans to relocate their families to their communities [17]. Mostly affected were those operating small scale businesses in capital cities and prominent markets across the North East, North central and North West. A trader, Wale Obayo, who often shuttles between the north and Lagos, opines that he had to close shop for some weeks, citing uncertainties around the election: "Nobody wants to be caught up in violence of any type. If the travel is avoidable, the best bet is to avoid it for now" (The Guardian, 2019). The middle and upper classes also joined the migratory trail. For instance, the Nnamdi Azikwe International airport, Abuja, witnessed an upsurge in passenger traffic and flight operations on many domestic routes as many people travelled for the elections. Apparently to attract traffic during the period, an airline slashed its price in a "promo offer" for passengers-valid all through February.

Elites temporary relocation abroad: A common category of persons excluded from the franchise in Nigeria are those not resident in the country at the time of an election unlike other nationals (abroad) who can cast their votes in their respective embassies and consulates. The country’s electoral system exempts from electoral participation, those travelling out of the country (or away from their place of registration) on polling day. Thus, for those relocating during elections, this form of electoral migration is a recurrent ground for disenfranchisement. Weeks before the 2019 elections, just like the previous ones, as many Nigerian voters were approaching the polls with every sense of trepidation, the privileged elites made, as common practice, preparations for temporary relocation abroad.

It should also be emphasized that the huge divide between the supporters of the two major presidential candidates, made the election look more like a war situation, prompting politicians and business elites to leave the country in droves. Little wonder, between January and the first week in February, many prominent families, according to the Punch Newspaper, had bought tickets to travel out of the country with top destinations like Dubai (United Arab Emirates), Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom.

Election duty/professional migration: This form of migration encompasses those on official duty like military/police personnel, election observers and media practitioners. A greater number of these Nigerians are deployed to different communities, local councils and states outside where they registered. Even those who, by coincidence, remain where they registered usually find it unethical to exercise franchise given the porous secret balloting that exists at the polling stations. Though not tension-induced, this community of prospective voters who are in their hundreds of thousands forms a significant percentage of electoral migrants in Nigeria [18].

This trend persists because security services continued to play a critical role in elections after the country emerged from military rule in 1999. In spite of the court judgment that the deployment of the Nigerian military for election purposes is illegal and unconstitutional, 95 per cent of Nigerian army troops were engaged in security duties during the general elections. Also, the police spokesperson, Frank Mba, confirmed in his pre-election briefing that “almost every police officer in Nigeria (approximately 350,000) will one way or another be involved in policing the election”. By media accounts, approximately, between 8,000 and 30,000 personnel were deployed for the election in each of the 36 states of the federation besides the deployment of 24,000 armed mobile officers and 8,000 anti-terrorism police officers. This is in addition to other para-military operatives like the Nigeria customs service, the Nigerian prison service, the Nigeria immigration service, Nigeria security and civil defense corps etc. Similarly, the electoral body recruited over 814,453 ad-hoc staff and accredited 120 domestic observer groups, deploying a cumulative total of over 73,000 observers`.

Voters’ relocation to communities: As indicated earlier, the election fuelled a mass migration in the country because citizens were obligated to return to the states and communities in which they registered to cast their vote. Considering the fact that there are publicly known processes of transferring one’s registration point to current place of residence or work, why do many Nigerians, even within a homogeneous state like Ekiti, still prefer the conclave of their communities of origin to exercise their franchise? “If anything happens around the polling unit, I can quickly run home for safety”, a middle-aged female voter interviewed on the eve of the election told channels television station (2019), monitored by this author [19]. Many voters like her, who had witnessed unpleasant events around electioneering in the country, are usually worried changing their registration points.

The government declared a national holiday on Friday, a day before election, in an effort to accommodate roughly 73 million eligible voters, many of whom had to travel back to their polling places after a-week postponement. Millions of Nigerians went back to their hometowns to vote at great personal expense. In order to alleviate the financial strain, both main parties offered free buses to registered voters, while one national airline offered discounted flights for those with voter cards.

Migration of political miscreants ahead of election day: Many youth are hoodwinked into political violence through the umbrella of ethnic membership, party membership and religious sentiments and in some cases, state governors deploy their state’s resources to hire political thugs, targeting existing youth organizations for recruitment. Before the vote, parties’ supporters clash and politicians often deploy thugs against their rivals. Around voting, those same thugs invade polling centers and snatch materials and intimidate voters. For instance, less than 72 hours to the February 16 earlier scheduled elections, the Nigerian Army raised alarm over the alleged plan by some miscreants to use its uniform to perpetrate evils at the polling units. In Kano state, the police command arrested over 500 political thugs on the eve of election. Politicians who are responsible for sponsoring violence and security breaches to elections usually go through series of planning meetings and sometimes days of dinning and partying with these miscreants who are psyched to go and truncate elections. While some of the vehicles conveying these thugs were intercepted across different states of the country, many of the political miscreants (not known to residents/communities where they unleashed mayhem) still perpetrated crises around election days as reported by various news media. At the end of the 2019 general election, 58 Nigerians were reported killed, with many more injured.

Issues of insecurity and tensions around the elections

Elections do not necessarily cause violence, but the process of competing for political power often exacerbates existing tensions and escalates them into violence. Risk of electoral violence, given Nigeria’s ethnic cleavages and social inequalities, remained a real concern. Since the emergence of civil rule in 1999, electoral contests in the country are often plagued by procedural flaws, intimidation, violence, and all sorts of irregularities. Observable again in the pre-2019 elections were irregularities and violence that characterized party primaries as disagreements over candidates created animosities within parties. In the pre-election phase, the violence was principally among and between political party activists and supporters. As the election day nervously approached, at least before the postponement on February 16, Nigeria was almost grinding to a standstill: Land and sea borders had been closed, and military checkpoints sprang up, holding up traffic in busy cities. Already there were heightened threats of insecurity in different parts of the country, and this is coupled with a lot of perceived marginalization, anger, confusion, and economic challenges. As rightly noted by Verjee, et al.

Social and economic inequalities, ethnic and religious divisions, and structural weakness such as corruption and weak state capacity, remain prevalent across Nigeria and contribute to the risks of electoral violenc. Other important factors contributing to the risks of electoral violence have evolved since 2015, including changing forms of insecurity and the prominence of disputes within, rather than between, the political parties.

Like all post-independence elections, a range of factors actually conspired to heighten risks of bloodshed across the country. Other drivers of tension in the country which include deadly fought party primaries, events around previously staggered state elections, sponsored criminal gangs by political gladiators, widespread popular distrust of security agencies, misgivings about the electoral commission’s neutrality and election postponement, widespread dissemination of fake news/hate speech, and the prevalence of conflict and deadly criminal violence in parts of the country, are discussed below.

Perennial security challenges in the country: Nigeria is facing security challenges involving growing farmer-herder violence, unresolved grievances in the oil-rich Niger Delta region, separatist tensions in the Southeast, restiveness among segments of the country’s minority Shiite population, and growing criminal violence in Nigeria’s rapidly expanding urban areas coupled with insecurity in the Northern region of the country remained a major election issue for Buhari, as extremist group Boko Haram continued to attack soft target and military formations. Civilian impact included heightened displacement, constrained movement and subsequent humanitarian needs. There were allegations that politicians in many states mobilized and armed criminal gangs ahead of the elections in order to harass their opponents as well as to intimidate and disenfranchise the voting public. For instance, on the eve of the general elections, at least 66 people were confirmed killed in attacks across eight settlements in the country's Northwest.

Electoral management body and sudden election postponement: Incredibly, just hours before the election was due to begin, Nigerians were awakened to find it delayed a week because “it was no longer feasible to hold free and fair elections on February 16 due to logistical problems”. The electoral commission chairman denied political pressure had played any part in the decision. This was after he had been repeatedly assuring Nigerians and international observers that the elections were going ahead. Earlier, several of the commission’s offices around the country were set on fire, resulting in thousands of electronic smart card readers and voter cards being destroyed. In an already tense political environment, the sudden election postponement heightened public anxiety, “raised political tempers, sparked conspiracy claims and stoked fears of violence, including terrorist attacks and post-electoral unrest”. People all over the country expressed their disappointment. Given the fact that past elections in the country were marred by violence, intimidation and ballot-rigging, the postponement raised the possibility of unrest and instantly, in spite of the assurances from the electoral body, threw the country into renewed political uncertainty.

Expectedly, the whole country was in frenzy as threat posed by the arming of rival political supporters and desperate politicians began to talk tough after the postponement. As if to further ignite the already tension-soaked atmosphere, two days after the postponement, President Muhammadu Buhari, while speaking at a televised APC caucus meeting in Abuja, warned those planning to disrupt elections or snatch ballot boxes that they would pay with their lives: "I have directed the police and the military to be ruthless. I am going to warn anybody who thinks he has enough influence in his locality to lead a body of thugs to snatch ballot boxes or disturb the voting system, will do so at the expense of his own life". For many Nigerians, the statement had the potential of emboldening trigger-happy security agents to take the law into their hands and could lead to the killing of innocent Nigerians who wanted take part in the rescheduled February 23rd polls.

Political gladiators, fake news and hate speech: Few weeks before the election, disinformation became a common strategy used by the political class to weaponise their agendas. All the candidates of major and minor political parties in the country took to social media in their bid to woo supporters. Political actors willingly took advantage of the existing gaps-perceived marginalization, anger, confusion and economic challenges to misinform, promote apathy and skew peoples voting choices during the election. Written posts, photos and videos were shared on social media platforms, publicly on Facebook and in private WhatsApp groups, spreading unsubstantiated rumours about the candidates. Typical of Nigeria’s election season, inflammatory statements capable of posing a serious threat to peaceful elections were made by political gladiators. Some governors also became vociferous on the election and contributed to the high political temperature in the country. For example, governor Nasir el-Rufai of Kaduna State threatened that foreign nationals who interfere in the general elections would be given a “body bags treatment”. A body bag is one used for carrying a corpse from a battlefield or the scene of an accident or crime to either a mortuary or place of burial. The governor’s threat came barely a week after the Federal Government accused foreign powers, including the United States (U.S.), United Kingdom (U.K.) and the European Union (E.U.) of actions that could be deemed as interference, and warned of consequences. His words: You can comment, but when you make statements on the internal affairs of a country without facts, that is interference and is very irresponsible. Those that are calling for anyone to come and intervene in Nigeria, we are waiting for those that will come and intervene, they will go back in body bags.

Consequently, the PDP threatened to jettison the peace pact it signed with the Abubakar Abdulsalami-led National Peace Committee (NPC) regarding the peaceful conduct of the presidential election. In another development, Rivers state governor, Nyesom Wike in an interview with premium times (2018), claimed that the government was ready to kill him and several other Nigerians in order to cheat in the 2019 general elections. He said he was ready to make the sacrifice, calling the federal government "a dictatorship in civilian uniform". In another instance, he opined: “They want rivers state by all means. Even if it means killing 500 people. But they will die, not us. We are prepared for the elections because we have something to tell the people”.

Events around previously staggered state elections: A few months to the general elections, the staggered governorship elections conducted particularly in Ekiti and Osun states, saw many instances of abuse of incumbency, widespread vote buying, acts of violence and other illegal voter inducements, dissemination of fake news and hate speech on social media. Events around these elections precipitated security concerns among voters and political observers. Indeed, as a number of these security crises intensified across the country, political actors took advantage of this to misinform, promote apathy or skew people’s votes in the build-up to the election. As the general elections drew near, political rhetoric was fierce, at times vitriolic just as information manipulators created a threatening environment in which many people began to entertain fear. It could be inferred from the foregoing that election preparations actually took place amid complex security challenges that overstretched the Nigerian security forces and raised tensions among the citizens, prompting different pre-election possible scenarios analyses (Table 1).

I hereby reproduce possible-scenario-analysis I did a few days before the election depicting three conceivable ways it could go as published by the African media.

| The best-case-scenario | There is a free, fair and credible election devoid of manipulation, violence and logistic inadequacies. Eligible voters cast their votes in a conducive environment, witnessed by election observers and party agents. Over seventy percent of registered voters turn out to vote. INEC declares one of the 73 presidential candidates as duly elected, meeting all requirements. Other candidates congratulate him/her in the spirit of sportsmanship. |

| The worst-case-scenario | The election witnesses a large scale of rigging evident in destruction of ballot boxes and falsification of results; violence during polling and collation of votes; Killings and intimidation among others. Low turn-out characterizes every polling unit, recording less than thirty percent. Declaration of results by INEC (by announcing a winner) ignites further violence across the country as political parties display different conflicting results favorable to them. Recourse to litigation is considered a futile exercise in such circumstance just as the international community bemoans the charade. The country is engulfed in anarchy and the military strikes to save the situation! |

| The reality-case-scenario | Voting takes place across all the 774 LGAs though with some irregularities in administrative procedure-late arrival of voting materials, inexperienced ad hoc staff-underage voting and vote trading. In a few polling units, there are reports of ballot snatching and violence. The social media is bombarded with different results by interested parties. Two days after, INEC announces one of the two dominant parties’ presidential candidates (Abubakar Atiku of PDP and Muhammadu Buhari of APC) as the winner of the election, in a keen contest that records 47-50 percent margin. The remaining three percent is shared among the other 71 parties that field candidates. A mixture of joy and sadness rent the air depending on the stronghold of the “winner” and the “loser”. Other smaller political parties naturally go into momentary stillness while a few align with the winner. The second runner-up vows to “vehemently” challenge the result in court. But the country still wobbles on the path of puzzling democratic experiment! |

Table 1: Possible election outcome scenarios.

Discussions

How do tensions and electoral migration impact on the election outcomes?

Obviously, obstacles to voting and distrust in the electoral process have repercussions for representational democracy, leading to participation gaps across demographics. A number of factors-revolving around security vulnerability and fake news manufacturing-may have undermined the election outcomes because tensed election atmosphere has a strategic way of hampering and violating the environment of a free, fair and credible election. Put differently, tension around election period can affect the direct participation of the constituency and candidates in the campaigns and it can interfere with their behavior towards and perception of democracy.

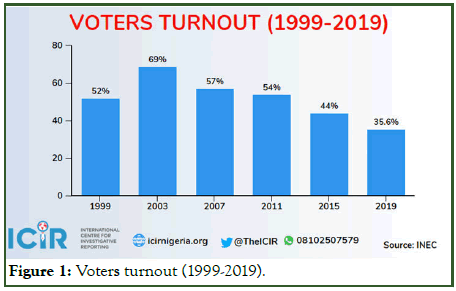

One major way in which tension-induced migration affected the 2019 elections is the level of voter turnout. For instance, while over 84 million eligible Nigerian voters were expected at the polls, the voter turn out only affirmed less than 40 percent of the number.

Precisely, the overall turnout for the presidential elections was 28, 614,190 which is 35.6 percent of registered voters, making it the lowest of all recent elections held on the African continent, according to the data from the International Institute for democracy and electoral assistance.

An interrogation of two states-Lagos and Rivers readily attests to the abysmal low turnout in the election. They are cosmopolitan states. Indeed, Lagos is the Nigeria’s most cosmopolitan state as well the richest state in the country, with an estimated 20 million residents. It has a total of 6,570,291 registered voters but only 17.25 per cent (1,089,567) of the number voted in the national election. In rivers, there are 3,215,273 registered voters but only 19.97 per cent (642,165) of the total registered number voted in the presidential election. Also, millions of eligible voters in Nigeria stayed away from casting their ballot to elect governors and state assembly members in the March 9 election. In fact, turnout has been declining since the 2003 presidential election. The graph below clearly shows the percentage of voters’ turnout between 1999 and 2019 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Voters turnout (1999-2019).

There is no empirical data to affirm that this low turnout could be solely adduced to voter migration as there are other factors including voter apathy, postponement of the election and fear of violence among others. For instance, the level of criminal violence greatly impacts citizens’ decision to participate politically, their forms of participation, and the logic of their vote choice. Just hours before the February 23 polls were set to open, suspected Islamist attacked a north-eastern Nigerian town, forcing residents to flee. Despite the efforts of the relevant authorities, including INEC, the Nigeria police and the Nigerian Army, the polls were significantly marred by bloodshed, widespread irregularities and voter suppression. Violent clashes involving voters, electoral officials, and security forces occurred in a few states, often over allegations of vote fraud. The situation room-which represents more than 70 civil society groups, confirmed that as many as 39 people were killed across the country during the February 23 presidential election. In spite of the secret ballot system in operation, there were violations of voter privacy due to atmosphere of blatant intimidation or willingness to negotiate cash for vote.

Curbing the anomalous trend: Stakeholders’ expected intervention

It should be emphasised that only a peaceful and successful general election can enhance our quest for democratic consolidation. Thus, from all indications and concerns expressed by stakeholders and given the history of violent political confrontation in the country, there is a growing sense of urgency for new actions to be taken regarding protection for future election security. As nearly 95 percent of all electoral violence takes place before elections, early warning requires early action to leverage political will and financial capital to forestall violence. Bearing in mind that some new democracies are experiencing political instabilities with their attendant disastrous consequences as a result of faulty electoral processes, it becomes imperative that the sanctity of balloting should be safeguarded by all “electoral integrity agents”: Governmental enforcement institutions, such as election management bodies, investigatory bodies and prosecutorial bodies; social enforcement institutions, including political parties, “watchdog” organizations, nongovernmental organizations and media; and international assistance and electoral observation organizations supporting these electoral integrity agents. A number of recommendations are made here for these agents seeking to strengthen electoral integrity.

One, comprehensive electoral violence scenario and action plans should be put in place and completed in advance of future elections and communicated widely with stakeholders in the country. Civil society has a particular role in promoting a peaceful electoral environment. Thus, local civil society and media organizations working toward transparency and accountability should be empowered with in order to engage in electoral violence prevention through voter education, election monitoring and peacebuilding activities (mercy corps, 2019). Voter education in particular helps people understand that while countrywide problems need to be dealt with, participation in local elections is one way of taking action to fix the situation in their own neighborhood. Collier and vicente’s (2014) field experiment found that an anti-violence campaign, based on encouraging electoral participation through town meetings, popular theatre, and door to door distribution of materials, had a measurable effect on reducing the level of violence and voter intimidation in an election in Nigeria.

Essentially, the capacity of media to professionally self-regulate the sector should be supported. Such anti-violence campaign has the potency of increasing the sense of security to the general population. The promotion of a constant, open political dialogue through unprecedented levels of consultation, conflict mitigation and resolution mechanisms is a prerequisite for conducive political environment. This will reduce tension and unnecessary relocation of Nigerians to different parts of the country or abroad considered as a temporary refuge.

Two, compliance with electoral laws and regulations are essential to the conduct of free, fair and credible elections and the ready acceptance of results. The electoral reform committee set up after the 2007 elections identified the weakness of the enforcement regime and the attitude of the political class as the two primary problems facing credible elections in Nigeria. The modern regulatory structure seeks to regulate public conduct at election time by laying down criminal offences. Enforcement of these laws by appropriate security operatives is also germane with a view to deterring prospective offenders because, in the past, most perpetrators from all sides of the political spectrum have always escaped without facing justice. In addition to building enforceable rules into the electoral law, parties or candidates can express their mutual commitment to an orderly process. Similarly, it is expected that adequate security be provided by the security agencies without fear or favour, while they remain politically neutral before, during and immediately after elections. Security forces must work carefully with other rule-of-law actors to include investigators and prosecutors as well as judges and other dispute resolvers.

Also, law enforcement agencies should be adequately prepared at all levels with information about the electoral law, their role in elections, the role of the civil authority in elections, among others. For security forces to rapidly respond to a crisis and for civilian authorities to mediate electoral disputes, valuable tools-security and civilian rapid response mechanisms are also needed with a view to providing specialized quick reaction forces before, during and after elections. Lastly on this point, electoral security efforts need to be tailored to address concerns relating to the specific electoral phases, the multiplicity of actors, and the motives and manifestations of threats, considering the dynamism and complexity of electoral processes and electionrelated violence. The body of knowledge associated with election security should be built up essentially from direct experience of problems that have arisen and ‘solutions’ that have either worked or failed not only in the country but in other climes.

Three, conducting political party workshops to foster negotiation among rivals and to work with them to arrive at mutually acceptable codes of conduct are useful ways to build confidence, relationships, and trust among contending party cadres. The general atmosphere should be conducive for political activities of both the incumbent and the opposition particularly in pre-election period. In other words, competing political parties and candidates must show willingness to conduct themselves peacefully and fairly. Incumbent leaders must set a tone of tolerance and respect for the election process. Nigeria should also adopt a wide range of measures to promote internal democracy within political parties as the best guarantee of entrenching democracy. It is also important to support efforts that strengthen the credibility and capacity of electoral institutions and the electoral process to ensure the elections are credible and the outcome legitimate and acceptable to all stakeholders.

Four, in an era when smart phones have become ubiquitous and the internet plays an integral part in most people’s lives, electronic voting system should be introduced to allow voters exercise their franchise even in the comfort of their homes. The degree of sophistication of ICT equipment varies, but most EMBs in Africa are using technology to improve biometric voter registration, database management, verify voter eligibility, automate recording and counting of votes cast and transmission of election results (maendeleo policy forum, 2016). There are farreaching expectations that electronic democracy will increase political participation, and include previously underrepresented groups in politics. New communication technologies might foster participation in elections if they simplify the timeconsuming process of voting, and thereby attract additional voters. Though not fully secured against hackers, internet voting systems allow citizens the convenience of casting their vote online without the need to visit polling stations could help to reverse a worrying decline in voter turnout (European parliamentary research service, 2018). In a developing democracy like Nigeria, where elections have often been marred by fraud, electronic vote-casting is rightly or wrongly-often seen as a means of ensuring a more credible poll. Also, Nigerians in the Diaspora (with their contributory power to the economy) should be allowed to participate in the national elections of the home country like many other countries that have expanded the participation of their citizens living abroad through external voting. According to the federal government, over 17 million Nigerians live in one country or the other outside their home country. There should be a concerted effort to make voting as easy as practicable in any part of the country (world) where they reside.

Lastly, as a matter of necessity, confidence in the electoral process and integrity in the institutions mandated to conduct elections should be built and should be a continuous process instead of one-stop, periodic election-year support. If stakeholders conform with well-known principles of electoral engagement such as a respect for political rights, a level playing field, transparency, fairness, integrity, among others, the foundation for building public confidence would have been solidly laid. Given the fact that elections are processes to confer legitimacy to govern, and to peacefully resolve political competition in a democracy, participation which is a foundational virtue of our democracy, must be guaranteed. It should be noted too that if there is an opportunity to diligently and transparently review the election outcomes (or other decisions affecting them), preferably by a body that is independent of both the government and the election commission, voters and contestants will have greater confidence in a process (Halff, n.d). In view of the fact that government has an affirmative obligation to remove any unnecessary obstacles to civic engagement being the election manager, it goes to say that it must guarantee a level playing ground all prospective voters.

Conclusion

Although multi-party election has clearly become a regular institution in Nigeria, there are doubts about the value and quality of the elections conducted so far. Only when elections are credible can they legitimize governments, as well as effectively safeguard the right of citizens to exercise their political rights. As established in this essay, in spite of six consecutive election cycles in the country, the process has continued to suffer from irregularities, intimidation, and violence. These persistent cases of electoral violence create obstacles to democratic consolidation as the right to vote may not be guaranteed for many people across the country and the political trust, considered as a necessary precondition for democratic rule, may not be earned. But confidence in electoral democracy, as recommended in the previous section, is not a one-off achievement; it requires sustaining and strengthening the quality of elections, at all levels. A credible and peaceful election has the potency of strengthening Nigeria’s democracy and its institutions while forestalling avoidable migratory movements during future elections. Unnecessary barriers on the franchise, even if they affect all voters equally, should not be allowed by the government so as to encourage adherence to democratic values, a greater propensity to vote and create much less distrust between the masses and the ruling class.

Finally, it is believed by many Nigerians that there should have been significant improvements in the process after two decades of democratic experiment. The story, however, is still the same: Violence, ballot snatching, voter apathy, vote buying, militarisation, ethno-religious clashes and results manipulation. Globally, the democratic culture and the rule of law underpin the democratic process. If these issues are not addressed (particularly by not enforcing the template of crime-andpunishment during elections) preparations for future elections will always, as a matter of necessity, include voter migration to places considered safe haven. And as both viable and desperate candidates compete for political space, future electoral events will become more hotly contested in Nigeria. At least, while counting votes, human bodies should be spared!

References

- Dustmann C, Vasiljeva K, Piil Damm A. Refugee migration and electoral outcomes. Rev Econ Stud. 2019;86(5):2035-2091.

- Aranha DF, Barbosa PY, Cardoso TN, Araújo CL, Matias P. The return of software vulnerabilities in the Brazilian voting machine. Comput Secur. 2019;86:335-349.

- Hjorth F, Larsen MV. When does accommodation work? Electoral effects of mainstream left position taking on immigration. Br J Polit Sci. 2022;52(2):949-957.

- Cutts D, Goodwin M, Heath O, Surridge P. Brexit, the 2019 general election and the realignment of British politics. Polit Quarterly. 2020;91(1):7-23.

- Gessler T, Toth G, Wachs J. No country for asylum seekers? How short-term exposure to refugees influences attitudes and voting behavior in Hungary. Polit Behav. 2022;44(4):1813-1841.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ortiz Barquero P. The electoral breakthrough of the radical right in Spain: Correlates of electoral support for VOX in Andalusia (2018). Genealogy. 2019;3(4):72.

- Marchal N, Neudert LM, Kollanyi B, Howard PN. Investigating visual content shared over Twitter during the 2019 EU parliamentary election campaign. Media Commun. 2021;9(1):158-170.

- Ehin P, Solvak M, Willemson J, Vinkel P. Internet voting in Estonia 2005–2019: Evidence from eleven elections. Gov Inf Quarterly. 2022;39(4):101718.

- Kavanagh NM, Menon A, Heinze JE. Does health vulnerability predict voting for right-wing populist parties in Europe?. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2021;115(3):1104-1109.

- Biro-Nagy A. Orban’s political jackpot: Migration and the hungarian electorate. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2022;48(2):405-24.

- Colantone I, Stanig P. The surge of economic nationalism in Western Europe. J Econ Perspect. 2019;33(4):128-151. [Crossref]

- van Leeuwen ES, Vega SH. Voting and the rise of populism: Spatial perspectives and applications across Europe. Reg Sci Policy. 2021;13(2):209-219.

- Carey S, Geddes A. Less is more: Immigration and European integration at the 2010 general election. Parliam Aff. 2010;63(4):849-865.

- Bratti M, Deiana C, Havari E, Mazzarella G, Meroni EC. Geographical proximity to refugee reception centres and voting. J Urban Econ. 2020;120:103290.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palop-García P, Pedroza L. Passed, regulated, or applied? The different stages of emigrant enfranchisement in Latin America and the Caribbean. Democratization. 2019;26(3):401-421.

- Lutz P. Variation in policy success: Radical right populism and migration policy. West Eur Polit. 2019;42(3):517-544.

- Rugh JS. Vanishing wealth, vanishing votes? Latino homeownership and the 2016 election in Florida. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2020;46(18):3829-3854.

- Zappettini F. The Brexit referendum: How trade and immigration in the discourses of the official campaigns have legitimised a toxic (inter) national logic. Crit Discourse Stud. 2019;16(4):403-419.

- Dennison J, Davidov E, Seddig D. Explaining voting in the UK's 2016 EU referendum: values, attitudes to immigration, European identity and political trust. Soc Sci Res. 2020;92:102476.

Citation: Omilusi M (2023) Voting with Oneâ??s Feet or for Oneâ??s Future? Electoral Migration, Voter Vulnerability and the 2019 General Elections in Nigeria. Global J Interdiscipl Soc Sci. 12:040.

Copyright: �© 2023 Omilusi M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.