Indexed In

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Review Article - (2024) Volume 9, Issue 4

Traumatic Memory and Dream Process: From Unconscious to Consciousness

Katerina Mangana*Received: 04-Jun-2020, Manuscript No. JFPY 24 4729; Editor assigned: 09-Jun-2020, Pre QC No. JFPY 24 4729 (PQ); Reviewed: 23-Jun-2020, QC No. JFPY 24 4729; Revised: 15-Jul-2024, Manuscript No. JFPY 24 4729 (R); Published: 12-Aug-2024, DOI: 10.35248/2475-319X.24.9.351

Abstract

Dream process is essential for our body and mind. It is not just a bio-data, it is a meaningful experience that helps the human being to grow, classify their memories, elaborate their feelings and inner repulsed desires and conflicts. Traumatic memory can sabotage this process; block the memory network disrupting the streams of communication between unconscious and consciousness. In the therapeutical context dreams are of the most powerful and revealing material. They can unlock crucial points of the analytical process as shown in the short clinical presentation.

The topic I am about to present concerns the traumatic memory and the dream process from a psychoanalytic approach. We know that dreams are of great importance in psychoanalysis but also in the psychosomatic since everything a human being experiences has an inscription on both soma and mind on the psychosomatic unity. Our body always participates in conflicting and traumatic situations, especially when these can be neither represented nor contemplated.

Keywords

Waste; Management; Racism; Legal; Toxicity

Introduction

Trauma results from one or more events that took place when the person was unable to neither think about it nor elaborate it. We talk about preverbal trauma when the little child is still unable to speak, to do something to change the situation. Sandor Ferenczi in 1932 describes trauma as “a shock that is an annihilation of self regard, of the ability to put up resistance and to act and think in defense of one’s own self [1]. He suggests shock can be purely physical purely moral or both physical and moral. For Ferenzci trauma occurs as a result of the absence of the maternal object when the subject-infant is in a state of despair. He gives significant importance at the conditions and at the quality of the traumatic experience based on the maternal psychic function and the traces that this one is leaving in their child psychic function. The immature ego is left in a state of severe distress and helplessness. In the current psychoanalytic literature trauma is described as the flood of emotional burdens that provoke feelings of vulnerability or of agonizing despair. Traumas are measured by the quality and quantity of the disorganization they generate rather than the nature of the event that precipitates them. Trauma is about predictability and trust. Things that our patients mostly demand from us; true relations and essential love cannot flourish if trust is not on the table [2]. We must believe in our internal gods, our parental figures, otherwise we have to live in a constant state of despair throughout our lives.

Literature Review

Our soma is directly involved in the traumas of the soul. D. Anzieu has given us the notion of the Ego-skin that describes how our skin can be conceived as a psychic form that embraces and reunites the self, acts as a protective shield for the organism and a surface of exchanges with the environment that allows separation and communication. It is also a surface on which inscriptions of symbolization are taking place. Bion thought the skin as a contact barrier that allows access into our internal world, into our unconscious [3]. The dream process is a psychosomatic experience, influenced by our psychic function and potential, the quality and quantity of our traumas, along with the quality of our mental function. In ancient Greece, in the sacred place of the temple of Asklipios, dreams were a healing process called falling to sleep. When every other attempt of treatment had failed the patients, they were put to sleep helped by herbal infusions and had strange dreams.

The following day they would recount their dreams to the temple curators. Based on the narration of the dreams they provided some cure, often merely a placebo, but most of the patients believed indeed that some god had visited them in their dreams and they would find their good health again [4]. It was Aristotle who posed the first questions of a more scientific approach for the dream process; do the dreams transmit some knowledge and of what kind, do they want to tell us something, is their source the human being or the gods. He will connect the dream process with the human imagination, defining the dream as presentations occurring directly from the fantasy function and indirectly from the function of the sensorial organs. Aristotle said that “There is nothing, no matter how irregular, unbridled and monstrous it might be that can be presented in our dreams”. Hippocrates wrote that during sleep the soul does all the functions both of body and mind. Since then, neurosciences have given us the knowledge that our senses create and store their stimulations even when the external trigger that created them is no longer present. We need dreaming, it is necessary for our emotional balance and consolidation of the day’s learning.

We also know that in a biological level, our dreams show the impressions that our brain produces in a calm state, protected by the noise and the storms of the senses during daytime. When we sleep our prefrontal cortex that acts as inspector of our reactions takes time to relax, so in our dreams we can be aggressive, versatile, unstable and lose our critical mind [5]. Finally, in the REM phase of sleep our brain activity is totally driven by the amydgala. Amygdala embodies mainly unconscious traces of experiences and functions as base of emotions.

But dreaming is not all about biology. Departing from the base of bio-data, (the capacity provided by our brains to dream), human beings proceed to the experience of the dream. From the biological reality of dreams one gradually encompasses in the psychic apparatus the experiences and the desires they have lived and through the dream process they elaborate them-restructure them-and even reformulate them. This is not given simply as biological information; it is an outcome of a long maturing process. The first narrative inner action a human being has is to dream; dream process precedes verbal ability. It is of capital importance for the development. D. Winnicott stresses out that after nine months an infant has been breastfed approximately a thousand times and that gives him a sufficient amount of positive memories for pleasant dreams [6]. He also observed that a complete and robust dream characterizes the period just before a child’s 5th year. It is the period during which the child is involved in a triangle of human relationships. In a full dream the biological drive that we call instinct becomes acceptable. In the dream process and the possible fantasies of everyday life the child’ s somatic functions are involved into passionate human relationships, with all the love, hate and conflicts that go with it.

Traumatic memory can affect quality and quantity of the dream process. Traumatic situations that took place in a preverbal level of development can heavily affect both explicit and implicit memory. Also during other phases of a lifetime, trauma can be rejected from consciousness when it is unbearable to elaborate it. I think we all have encountered patients without memories from their childhood or certain stages of their lives. “I can’t recall/ nothing important” gaps in memory and breaks in the continuity of thinking disturb the capacity of having a full dream, as described by Winnicott. Absence of memories suggests that the ego is unable to contain, elaborate and transform the traumatic elements. But this amnesia contains the presence of what is forgotten: Traumatic experiences may be kept outside the memory network while the psychic scene is dominated by compulsive repetitions obliging the person to relive again and again what the ego in a conscious level is seeking to avoid [7]. Everything happens in the present, traumatic potential is overwhelming, shuts down mental life, damaging representations, emotions, leaving the psychic field devoid of positive experience.

Discussion

A very recent example is the pandemic of COVID-19. This severe health crisis affected/in a considerable percentage/the quality and the content of people’s dreams. The stress we are experiencing may be manifesting in our dreams’ content, as presented in an online survey: Dr Barret, from Harvard Medical School, gathered more than 6000 dreams, from more than 2500 responses. We see, he says, that our unconscious looks more scared than we’re feeling during the day or the opposite: It can provide us with more optimistic perspective that we have not thought by now. He registered a lot of anxiety and bug dreams. In the psychosomatic literature these are called operational dreams [8]. Not enough symbolization, no metaphorical meanings, just visual representation of inner anxiety. During tough times it is usual to become more operational in our lives as a reflex of protection, both somatic and psychic. For people in the front line, the survey gives a big percentage of nightmares, trauma like nightmares, meaning that the trauma is with no elaboration, no psychic translation, unable to be transformed in a more symbolic and metaphorical level.

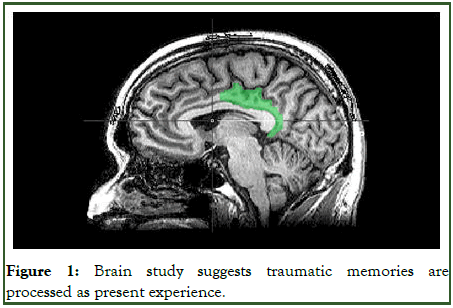

Among the material that a patient brings in the psychoanalytical relationship the dreaming material is the most powerful and the most revealing. Every dream contains our vision of the world we live in, our emotional state and it is an attempt to resolve a conflict, the latter being the most important in therapy. Conflicts that remain present in out psychic function have implications and result in our behavior in the external world. Freud realized that there must be a particular connection between something that happened during the day-which becomes material for the dream- and an infantile experience, usually repulsed [9]. In Wolf Man, he observes that the dream process gives form to trauma and enables the psychic apparatus to register a trauma which until then it could not be represented. Such dreams may cause psychosomatic disorders since they reveal traumas, from the unconscious to a conscious level. Bion supports that to dream is to think. That is to say, dreams provides us an inner place to visit our psychic world while we are sleeping, rethink about our emotions and experiences, give all our attention to this internal world we tend to ignore during day’s activities. It is the topos where we can have, with the minimum of interruptions, an insight communication with our unconscious. Traumatic memory can find space to reveal itself in the dream, but this memory comes to light once a certain level of security and trust is established between the analytical couple. Then dreams can be therapeutical, in a sense that they function against the creation of somatic symptoms. According to the Psychosomatic School of Paris, the more our mental function is developed the less we fear the risk of a somatic illness. P. Marty in 1984 concluded that our preconscious is the central regulator of our dreaming mechanisms along with those of somatic symptoms (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Brain study suggests traumatic memories are processed as present experience.

Figure 2: Representation of traumatic and stress change in brain.

But, as Andre Green wrote in “Le temps retrouve” if we luck the mediation of the narration, the sharing that takes place in the therapeutical context, all these treasures of the unconscious that a dream can enlighten, would not be able to reveal their secrets.

In the psychoanalytical couple the dreamer is the one who thinks and the analyst the one who understands these thoughts. An understanding beyond words, says Green, that has to do also with a non verbal message that needs an intelligence beyond words. To accomplish this understanding in therapy we use the free associations technique, to guess it and to spot it. The narration of the dream replaces the dream that was dreamed-objet lost forever-transforming the representation of thing to representation of word. Traumatic elements can intrude in every dream, trying to reduce the excitations through their repetitive action. Even if a dream is traumatic it defines a certain distance from the tangible reality, since it is a metaphor of it in a different level. In the therapeutical relationship when the patient recalls traumatic situations by the dream process they can include them in the relationship and their own narrations that reconstruct their history.

I recall the dream of a patient, a young woman who has been abused by her mother when she was a child. Her mother was beating her so badly that, as a result of inner protection, she literally had stopped feeling bitten or even pain. During her adolescence she presented bulimic disorder that followed her, with intervals in her adult life. She was also suffering from panic attacks. For a very long period in her therapy she used to say that she could not trust me. After some years, when a basic feeling of trust had been achieved between us she had this dream: She was performing in a theater stage wearing a mask of an old and ugly lady. She was suffocated with it but it was not allowed to take it off, the director would send her away, she would lose her job. Luck of air provokes a panic attack so she takes off the mask revealing a beautiful young face. And everybody applauses. End of dream.

Conclusion

In her associations she talks about the maternal stare, she always felt that her mother didn’t like her; she cannot recall a single glance of acceptance. She discovered a recollection of what she named “the cursed mirror”: When she was at the age of 14-15 she used to go to her mother’s bedroom, sometimes four, five, even six times a day. There was a big mirror there. And she was observing her body obsessively, as she said, to find if there was something wrong, like, she was too fat? She had cellulite? Then she would go to the kitchen, to eat and then she would vomit. A mirror transferred in the eyes of other people in her life, in her internal mirror too. Soma and soul terrors were permitted to be relived in the following period, her body image was improved along with her nutrition and the efforts to make peace with the guilty child inside her mind that she thought it was ok to be beaten. Trauma had an image and a name, a title, thanks to her dream. Thanks to the narration of it; the dream that we shared.

Before closing this paper I‘d like to quote Christopher Bollas, from his book Cracking Up: By transforming the past into a history the psychoanalyst creates a series of densely symbolic stories that will serve as ever-present dream material in the patient’s life, generating constant and continuous associations. And this imaginative and symbolic energy makes this past available for the self’s future.

References

- Mancia M. Implicit memory and early unrepressed unconscious: Their role in the therapeutic process (How the neurosciences can contribute to psychoanalysis). Int J Psychoanal. 2006;87(1):83-103.

- Scalabrini A, Esposito R, Mucci C. Dreaming the unrepressed unconscious and beyond: Repression vs. dissociation in the oneiric functioning of severe patients. Research in psychotherapy (Milano). 2021;24(2):545.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fischmann T, Russ MO, Leuzinger-Bohleber M. Trauma, dream and psychic change in psychoanalyses: A dialog between psychoanalysis and the neurosciences. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:877.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mancia M. Dream actors in the theatre of memory: Their role in the psychoanalytic process. Int J Psychoanal. 2003;84(4):945-952.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fischmann T, Ambresin G, Leuzinger-Bohleber M. Dreams and trauma changes in the manifest dreams in psychoanalytic treatments–a psychoanalytic outcome measure. Front Psychol. 2021;12:678440.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spector Person E, Klar H. Establishing trauma: The difficulty distinguishing between memories and fantasies. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1994;42(4):1055-1081.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Modell AH. Psychoanalysis, neuroscience and the unconscious self. Psychoanal Rev. 2012;99(4):475-483.

- Lynn SJ, Knox JA, Fassler O, Lilienfeld SO, Loftus EF. Memory, trauma and dissociation. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. 2004:163-186.

- Davidson AJ. Awareness, dreaming and unconscious memory formation during anaesthesia in children. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007;21(3):415-429.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Mangana K (2024) Traumatic Memory and Dream Process: From Unconscious to Consciousness. J Foren Psy. 09:351.

Copyright: © 2024 Mangana K. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.