Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- ResearchBible

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research - (2019) Volume 7, Issue 3

Older Adults and Sexuality in Israel: Knowledge, Attitudes, Sexual Activity and Quality of Life

Ahuva Even-Zohar1* and Shoshi Werner22Faculty of Health Sciences, Nursing Sciences, Ariel University, Israel

Received: 13-Aug-2019 Published: 04-Sep-2019

Abstract

Background: Sexual interest and activity continue to play a role in people's life as they age. However, research on this subject is limited.

Purpose: To examine knowledge about sexuality, attitudes towards sexuality and sexual activity, and the relationship of sexual activity to quality of life among older adults in Israel. Method: Data included 203 Israeli Jews, with an average age of 69.59. The participants completed questionnaires, through an Internet panel, about sexuality knowledge and attitudes, sexual activity, quality of life and a sociodemographic questionnaire.

Results: The results revealed that older adults continue to engage in sexual activities in later life. Knowledge and permissive attitudes are related to more sexual activity. Frequency of sexual activity was found as a predictor variable of quality of life, indicating a mediating effect on the relationship between attitudes towards older adults’ sexuality and quality of life. Men and older adults who have a spouse have a higher frequency of sexual activity than women and older adults who do not have a spouse. A correlation was found between the variables: health status, economic situation, education, and knowledge, attitudes, and sexual activity.

Conclusion: Similar to other societies, Israeli older adults are still interested in sex, and sexual activity contributes to their quality of life. The practical recommendations are aimed primarily at professionals working with the older adult population. The older adults should be encouraged to seek help in the event that problems arise. Educational programs should be designed for the older adults themselves and for professionals as well. Education should emphasize the benefits of older adults' sexuality; provide knowledge of current sexual behavior patterns, and the biological and psychosocial aspects of sexuality.

Keywords

Older adults; Sexuality; Quality of life

Introduction

Sexual interest and activity continues to play a role in people's life as they age. Older adults feel sexual desire, and they continue to engage in sexual activities, such as vaginal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation, even in the eighth and ninth decades of life [1-5]. Considering the increase in life expectancy and concurrent increase in the older population, research into the subject of sexuality in later life in Israel is very limited. This study aimed to fill this research gap.

Knowledge of sexuality and attitudes toward sexuality among older adults

Various studies have found relationships between knowledge about sexuality and positive attitudes toward sexuality and sexual activity [2,6-8]. Indeed, older adults with better knowledge about sexuality can understand the physiological changes related to the aging process and can maintain satisfying sexual activity leading to improved quality of life [7,9,10]. Attitudes toward sexuality have an important influence on sexual behavior and expressions of sexuality, and positive attitudes are also associated with continuing sexual activity into later life as well as frequent sexual activity [2,9,11]. In addition, some socio-demographic variables are related to sexuality in later life.

Socio-demographic variables and sexuality of older adults

Age and health status: Age is related to decline in the sexual aspects of life, as well as to the acquisition of knowledge and skills [12]. Good health is one of the important factors in maintaining sexual interest as expressed in various European countries [13]. However, the health problems that increase with age, such as functional decline or multiple concurrent diseases, cause problems in sexuality [4,14-16]. The most common form of sexual dysfunction among older men is impotence, and among women, the most common form of sexual disorder is caused by postmenopausal changes [17]. In addition, using medicines and drugs has a negative impact on sexual function [2,17]. Likewise, stress, anxiety, and depression lead to decreased sexual function in later life [18].

Marital status and gender: De Lamater noted that most sexual activity takes place in couples, and intimate relationships have a great impact on such activity [2]. However, men report they have more spousal or intimate relationships than women [3]. In addition, more positive attitudes toward sexuality and a higher level of sexual desire were found among older adults living with a spouse [9,19]. Indeed, widowhood among older women is a major reason for the decrease in sexual activity in later life [3,20].

The relationship between level of sexual desire and having a partner is stronger among women than among men [9]. Waite et al. found that among couples where the husbands score high in positive attitude to social situations, they show higher levels of sexual activity, and this is related to thinking about sex and believing sex is important [21]. However, the main reason reported by men for not having intercourse was due to personal reasons, whereas among women it was most often due to partner-related factors, or lack of a partner [2]. Clarke indicates a change among women who remarried after age 50 from an emphasis on the importance of sexual intercourse and passion to companionship, cuddling, affection, and intimate relationships [22].

Economic status: High income is related to higher level of desire, positive attitudes toward sexuality, and sexual knowledge [6,9].

Education: Sexual activity was significantly associated with higher education levels, and older adults with lower levels of education reported less sexual activity [8]. High level of education may also undercut the negative stereotypes of sexual expression by older adults [9]. Iveniuk contended that among men with a high level of religiosity, the desire for sex is lower than among less religious men [23]. Beckman et al. found improved sexual activity among older adults in recent years which they attribute to secular trends e.g., cohabiting and living separately which have become more common [1]. Regarding Judaism, David et al. maintained that Judaism has a positive attitude to sexual relations within marriage, viewing sexual relations as important not only for procreation but also for couples in later life as part of the marriage bond [24]. In contrast, the Catholic religion is reported to have negatively conditioned the sexuality of the Spanish senior population [16].

Sexuality and quality of life among older adults

Although sexual activity refers to physical and biological aspects, sexuality has a broader meaning which includes the social and emotional aspects, including expressions of love and affection. The World Association for Sexual Health emphasized that sexual health is related to the quality of life of people of different ages and different health conditions [25]. Sexuality in old age is, therefore, an important and central component in both the physical health and well-being of older people. Expressions of sexuality among older people affect their quality of life, improving their functional status, cognitive situation, and mood [1,3-6,8,26-31].

Satisfaction and the importance attributed to sexual activity are related to well-being. Thus, older women who reported more satisfaction with their sexual activity had better mental health compared to women with low satisfaction [32]. Lamater noted that men and women over 65 who rated the importance of sexuality for their well-being were more sexually active [2]. In addition, a positive relationship was found between attitudes toward sexuality and sexual satisfaction [33]. In a study that examined the relationship between sexual quality of life and aging, Forbes found that sexual quality of life and aging tend to decline during aging but the decline related to factors such as frequency of sexual activity and the amount of thought and effort invested in the sexual aspects of life [12]. These study results emphasize the importance of sexuality in successful aging.

The frequency of sexual activity in later life: A survey of adults aged 60 and over shows that more than half (53%) reported sexual activity in the preceding month, while the main factors in sexual activity were age, education, sense of self-worth, marital satisfaction, and length of marriage [17]. Similarly, the results of a survey conducted in the United States show that in the 57 to 64 age group, 53% have sexual activity but the prevalence declines with age. Among participants aged 75 to 85 years old, 26% have sexual activity. Also, women of all ages reported less sexual activity than men, and the reason is that they less frequently have a spousal or other intimate relationship [3]. Among a sample of 688 older Chinese people, it was found that 51.32% of men and 41.26% of women reported engaging in some form of sexual activity [34]. A survey conducted in eight countries in Europe (Sweden, UK, Belgium, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, and Italy) Nicolosi and in Australia Moreira found that sexual interest and sexual activity are widespread among older adults, but many experienced sexual dysfunctions and difficulties [35,36]. Nonetheless, few seek medical help; perhaps they do not perceive these difficulties as serious or disturbing. Indeed, Santos-Iglesias et al. found that about twothirds of their participants in their study who were in a current relationship had experienced at least one sexual difficulty, but only one-quarter were distressed about it [5]. Sexuality in late adulthood changes and includes a variety of expressions. Gott et al. noted that when full sexual intercourse is no longer possible due to physical limitations, physical intimacy through cuddling and ‘touching’ appears central to the well-being of older adults [37]. Thus, Santos- Iglesias et al. showed that older adults who were in a relationship engaged in frequent genital and non-genital sexual activity [5].

Older adults' sexuality in Israel

In 2017 the percentage of older adults over the age of 65 in Israel was 11.6%, and in 2040 is expected to rise to 14%, nearly two million people [38]. However, few studies have been conducted in Israel regarding sexuality in this population. Shkolnik and Iecovich examined in particular the relationships between migration status and sexual activity and satisfaction among older adults in Israel, and found the majority had some kind of sexual activity. Kasif et al. noted that interest in sexuality can increase in later life because of more free time following retirement and children leaving the home [20]. The results of Gewirtz-Meydan et al. described sexual motives by Israeli older adults such as to feel young again, to feel attractive and desirable, and lust to love [39]. Another research dealt with the ways Israeli older men and women cope with changes in sexual functioning such as a primary care provider or a counselor, or acceptance of the fact that sex was no longer part of life [40].

The present study

The review of literature points to sexuality as an important component of older adults' life that affects well-being and satisfaction with life. However, research on sexuality of older adults in Israel is scant, and there is a gap in the research regarding these subjects. Therefore, this study addressing the older adult population will contribute important knowledge.

Research questions: (1) What is older adults' level of knowledge about sexuality, and what are their attitudes towards sexuality in later life? (2) What is older adults' level of quality of life; the frequency of sexual activity, its nature, its level of satisfaction and associated difficulties? (3) Which variables predict older adults’ quality of life? In addition, based on previous studies and on the literature, we hypothesized: (1) Knowledge about sexuality in later life will be positively correlated with permissive attitudes towards older adults' sexuality and with the frequency of sexual activity among the older adults. (2) Sexual activity will be positively correlated with quality of life in later life. (3). Sexual activity will mediate between knowledge about sexuality and quality of life. (4) The sociodemographic variables: health status, age, education, and economic status will be correlated with knowledge about sexuality, attitudes towards sexuality, and frequency of sexual activity. (5) Differences will be found in relation to knowledge, attitudes, and frequency of sexual activity: (5.1) Men will have more knowledge, more permissive attitudes, and more sexual activity than women. (5.2) Older adults who have a relationship with a spouse will have more knowledge, more permissive attitudes, and more sexual activity than older adults who have no partner. (5.3) Secular older adults will have more permissive attitudes in later life than religious older adults.

Methods

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the University's Ethics Committee, where the researchers work. Signing informed consent was obtained from all participants after being briefed on the study purpose and confidentiality issues.

Data collection and procedure

The research was conducted through an Internet panel. The questionnaires (see below) were sent to 565 people over the age of 65, according to a profile of a survey pool of respondents drawn up by the survey company. Of the 565 people contacted, 262 people began filling out the questionnaires. Fifty-nine people responded partially, and their questionnaires were not taken into account. Each participant filled out the questionnaire after his/her consent was obtained and confirmed. The data were collected from October 2017 to January 2018. The sample included 203 participants with an average age of 69.59 (SD: 4.14). The age range was 65-87; 102 were men and 101 were women, most living in their homes (98%). This data is consistent with Central Bureau of Statistics data (2017), whereby which 96% of those aged 65 and over reside in their homes. Most of the study participants were married or living with a spouse. Most of them reported a good or a very good health condition. All the participants were Jews and concerning religiosity-most were secular. Table 1 presents the background data of the participants.

| Characteristic | N | % | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 203 | 69.6 | 4.14 | ||

| Gender | Women | 102 | 50.2 | - | - |

| Men | 101 | 49.8 | - | - | |

| Marital status | Single | 7 | 3.4 | - | - |

| Married | 136 | 67 | - | - | |

| Cohabitating | 15 | 7.4 | - | - | |

| Divorced | 16 | 7.9 | - | - | |

| Level of religiosity | Religious | 9 | 4.4 | - | - |

| Traditional | 38 | 18.7 | - | - | |

| Secular | 156 | 76.8 | - | - | |

| Years of education | 15.3 | 2.95 | |||

| Health status | Bad | 3 | 1.5 | - | - |

| Average | 33 | 16.3 | - | - | |

| Good | 111 | 54.7 | - | - | |

| Very good | 42 | 20.7 | - | - | |

| Economic status | Bad | 6 | 3 | - | - |

| Average | 37 | 18.2 | - | - | |

| Good | 118 | 58.1 | - | - | |

| Very good | 42 | 20.7 | - | - | |

| Residence | In my house | 199 | 98 | - | - |

| In home of relatives | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| In assisted living | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants (N=203).

Measures

Attitudes and knowledge regarding older adult's sexuality (ASKAS): The Sexuality Knowledge and Attitudes Scale [41] is a 60-item scale with two subscales (attitudes and knowledge), designed to measure attitudes and knowledge of sexuality in later life. The Attitudinal subscale consists of 26 items, with permissive attitude responses (e.g. Masturbation is an acceptable sexual activity for older females/males) and conservative responses (e.g. Aged people have little interest in sexuality). Respondents used a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to indicate their level of agreement with the item stated. Negatively worded items were reverse scored, and then all items were summed to reach the final score. A low attitude score reflects more permissive attitudes.

The Knowledge subscale consists of 34 items marked 1 (True), 2 (False), or 3 (Do not know answer) indicating the extent to which the participant is knowledgeable about sexuality in older age (e.g. Sexual activity in aged persons is often dangerous to their health and Sexuality is typically a life-long need). The score is the sum of the correct answers, and higher scores reflect greater knowledge. The questionnaire was translated both translations, into Hebrew (the language of the participants) and back translation by a professional translator. In previous studies, reliability of the ASKAS scale was high: α=0.85 for the attitude items and α=0.90 for the knowledge items [41]. In the present study, alpha values were high as well: attitudes toward aging and sexuality (α=0.86) and knowledge (α=0.80).

Quality of Life: The quality of life was examined using the general question of the questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization Quality of Life Group [42], which is a measurement tool for the self-reported subjective perception of people about their quality of life. A Hebrew version of the questionnaire was developed by Ben Ya'acov et al. [43]. The question in this study was: "Please rate your quality of life: 1.Very bad 2.Pretty bad 3.Not good or bad 4.Good 5.Very good."

Socio-demographic questionnaire: Respondents were asked to note their gender, age, and marital status, level of religiosity, economic condition, health status, and place of residence.

Questions about sexual activity: Respondents were asked to note the frequency of their sexual activity (have not had sexual activity for a long time; infrequently; often), the reasons they don't have sexual activity (do not have a spouse; not interested; another reason), the nature of sexual activity (mostly hugging and kissing; partial sexual activity; full sexual activity), difficulties in sexual activity always; most of the times; occasionally; never), satisfaction with sexual activity (not at all; to a small extent; to a moderate extent; to a great extent; to a very great extent), and sharing concerns about sexuality with a professional (yes/no).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS, version 22. Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe the socio-demographic variables, and the data relating to quality of life and sexual activity. To test the questions and the hypotheses, t-test, Chi-square, Pearson correlation tests, and a mediation model were conducted. A stepwise regression analysis model was conducted to determine which variables predict the quality of life of older adults. Finally, a summary model based on Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was conducted.

Results

Sexual knowledge and sexual attitudes of the older adults

The average score for sexual knowledge was 19.97 (SD=5.4), N=203, the range was 31.00 (minimum-0.00, maximum-31.00), and the median score of the study ASKAS questionnaire of the total 34 items about knowledge was 20.0. That is, the older adults in this study showed a moderate level of knowledge. The average score on sexual attitudes was 2.31 (SD=0.74, N=203), the range was 4.08 (minimum-1.19, maximum-5.27), the median score of the study ASKAS questionnaire about attitudes, which included 26 items on scale of 1 to 7, was 2.19.

That is, the older adults in this study showed a moderately permissive level of attitudes towards sexuality. A higher level of knowledge and more permissive attitudes were observed among men compared to women (knowledge M=20.6, 19.3; attitudes M=2.25, 2.35, respectively). However, no statistically significant differences were found.

Quality of life and sexual activity

Data on the level of quality of life, frequency and nature of sexual activity, satisfaction, difficulties in sexual activity, and sharing concerns with a professional on sexuality are presented in Table 2.

| Characteristic | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of quality of life (N=203) | Bad | 4 | 2 |

| Average | 25 | 12.3 | |

| Good | 11 | 54.7 | |

| Very good | 63 | 31 | |

| Frequency of sexual activity (N=203) | No, have not had sexual activity for a long time | 49 | 24.1 |

| Yes, infrequently | 64 | 31.5 | |

| Yes, often | 55 | 27.1 | |

| Yes, regularly | 35 | 17.3 | |

| Why do you not have sexual activity? (N=49) | I do not have a spouse | 20 | 40.8 |

| I'm not interested | 17 | 34.7 | |

| Another reason | 12 | 24.5 | |

| The nature of the sexual activity (N=154) | Mostly hugging and kissing | 8 | 5.2 |

| Partial sexual activity | 36 | 23.4 | |

| Full sexual activity | 110 | 71.4 | |

| Satisfaction with sexual activity (N=154) | Not at all | 1 | 1.3 |

| To a small extent | 16 | 10.4 | |

| To a moderate extent | 62 | 40.3 | |

| To a great extent | 56 | 36.4 | |

| To a very great extent | 18 | 11.7 | |

| Difficulty in sexual activity (N=154) | Yes, always | 2 | 1.3 |

| Yes, most of the times | 17 | 11 | |

| Yes, occasionally | 70 | 45.5 | |

| Never | 65 | 42.2 | |

| Consult a professional (physician, nurse, social worker) about sexual activity | Yes | 24 | 11.8 |

| No | 179 | 88.2 | |

Table 2: Quality of life and sexual activity among study participants.

Table 2 shows that most of the study participants reported a good (54.7%) and very good quality of life (31%).

Regarding data on sexuality-76% of the study participants have sexual activity, of these,17.3% have sex regularly, and 71.4% have full sex. Of the respondents, about half (47.7%) said that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the sexual activity. Furthermore, 45.5% of respondents indicated that they occasionally have difficulty in maintaining sexual activity. Of the 49 participants who indicated reasons for not having sexual activity, 40.8% stated that they have no a spouse, 34.7% said they were not interested, and 24.5% indicated other reasons like health problems, illness. In addition, most of the participants (88.2%) do not share their concerns about sexuality with a professional (a nurse, a social worker, a physician).

The relationship between knowledge, attitudes, frequency of sexual activity, and quality of life: To examine the first hypothesis, i.e., that knowledge about sexuality in later life will be positively correlated with permissive attitudes toward older adults' sexuality and with the frequency of sexual activity among the older adults, Pearson correlations were conducted. There was a significant positive correlation between knowledge about sexuality and permissive attitudes towards sexuality in later life (r=-0.32, p<0.001, N=203). (Permissive attitudes are in low scaling). A significant positive correlation was found also between knowledge about sexuality and frequency of sexual activity (r=0.14, p<0.01, N=203), and between permissive attitudes and frequency of sexual activity (r=-0.21, p<0.001, N=203). The first hypothesis was confirmed.

The second hypothesis, that sexual activity will be positively correlated with quality of life in later life, was examined using chisquared test. Levels of quality of life were divided into three levels: medium, good, and very good (Table 3).

| Level of quality of life | To medium | Good | Very good | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Frequency of sexual activity | Have not had sexual activity for a long time | 14 | 48.3 | 25 | 22.5 | 10 | 15.9 | 49 | 24.1 |

| Yes, infrequently | 13 | 44.8 | 41 | 36.9 | 10 | 15.9 | 64 | 31.5 | |

| Yes, often | 2 | 6.9 | 45 | 40.5 | 43 | 68.3 | 90 | 44.3 | |

| Total | 29 | 100 | 111 | 100 | 63 | 100 | 203 | 100 | |

χ2=34.1; p<0.001

Table 3: The relationship between frequency of sexual activity and quality of life (Crosstabs).

Table 3 shows that according to the hypothesis, there is a significant correlation between the frequency of sexual activity and quality of life. For the older adults who have sexual activity regularly or frequently, the better their quality of life is (38.1% and 30.2%, respectively), while for the older adults who do not have sexual activity or who rarely have sexual activity, their quality of life is moderate (48.3% and 44.8%, respectively). In addition, according to Pearson correlations there was a significant positive correlation between satisfaction with sexual activity and quality of life (r=0.42, p<0.001, N=154).

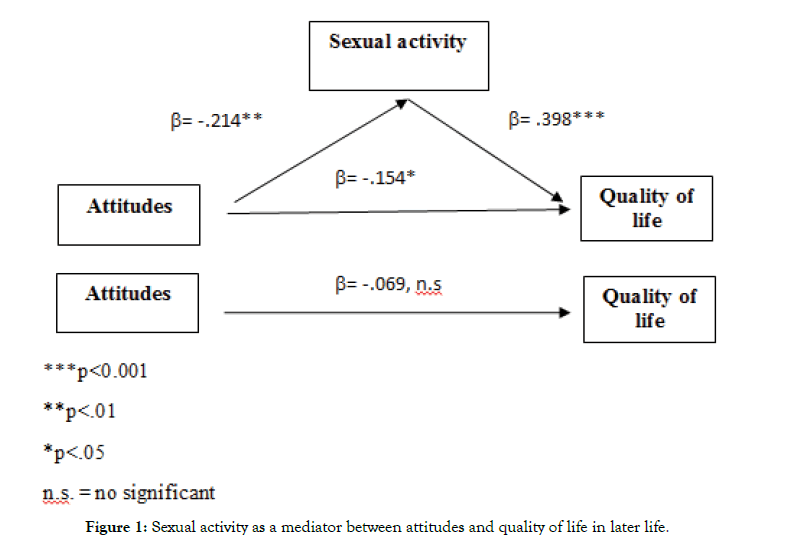

According to hypothesis 3, sexual activity was examined as a mediator between attitudes towards older adults’ sexuality and quality of life (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sexual activity as a mediator between attitudes and quality of life in later life.

The β-coefficient between attitudes towards sexuality (the independent variable) and sexual activity (the mediator) was -0.214 (p<0.01), and between sexual activity and quality of life (the dependent variable), β=0.398 (p<0.001). The coefficient between attitudes and quality of life was β=-0.154 (p<0.05). After we added the mediator variable to the regression equation, it was reduced to β=-0.069; no significance. To test the significance of this mediation, we applied the Sobel test. The -0.085 decrease in the β-coefficient was significant (Z=-0.2.77, p<0.01). Thus, sexual activity indicated a mediating effect on the relationship between attitudes towards older adults’ sexuality and quality of life.

Socio-demographic variables and knowledge about sexuality, attitudes towards sexuality, and frequency of sexual activity: Pearson correlations were conducted to examine the fourth hypothesis about the socio-demographic variable: health status, age, education, economic status, and knowledge about sexuality, attitudes towards sexuality, and frequency of sexual activity (Table 4).

| Frequency of sexual activity | Knowledge about sexuality | Attitudes towards sexuality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.02 | -0.001 | 0.008 |

| Health status | 0.26*** | -0.05 | -0.04 |

| Economic status | 0.37*** | -0.06 | -0.16* |

| Education | 0.16* | 0.17* | -0.17* |

*p<05; ***p<0.001

Table 4: Pearson correlation between socio-demographic variables and the dependent variables (N=203).

Table 4 shows that according to the hypothesis, the better the older adult's health, and the greater the frequency of sexual activity and the higher their quality of life. In addition, the better the older adult's health, greater the frequency of sexual activity. The more educated the person is and the more knowledge about sexuality in later life he has, the more permissive his attitudes toward sexuality are, and the higher frequency of his sexual activity. The better the older adult's economic status, the more permissive are attitudes toward sexuality, and the greater the frequency of sexual activity. With regard to age, contrary to the hypothesis, there was no relationship between the age of the older adult, his knowledge, his attitudes toward sexuality in later life, and the frequency of sexual activity. The fourth hypothesis was mostly confirmed.

To examine the fifth hypothesis, regarding differences between men and women, having a spouse and not having one, and between religious and secular older adults regarding knowledge, attitudes toward sexuality, and frequency of sexual activity in later life, t-test for independent groups was conducted. (The level of religiosity was divided into two groups: secular versus religious, while those who defined themselves as traditional were included with the participants who defined themselves as religious, due to the small number of religious participants). According to the hypothesis, men have a higher frequency of sexual activity (M=2.71, SD=0.089, N=102) than women (M=2.04, SD=0.105, N=101) (t=4.84, p<0.001). No differences were found regarding attitudes and knowledge. According to the hypothesis, older adults who have a spouse have a higher frequency of sexual activity (M=2.57, SD=0.081, N=151) than older adults who do not have a spouse (M=1.81, SD=0.132, N=52) (t=4.83, p<0.001). No differences were found regarding attitudes and knowledge. In addition, according to the hypothesis, secular older adults' attitudes regarding sexuality were more permissive (M=2.32, SD=0.083, N=156) than the religious participants' attitudes (M=2.55, SD=0.148, N=47) (t=- 3.13, p<0.01). No differences were found regarding knowledge and frequency of sexual activity. The fifth hypothesis was mostly confirmed.

In addition, we conducted a Pearson correlation to examine the sharing concerns with a professional about sexuality. The more difficult a person has in maintaining sexual activity, the more he shares his concerns with professional about sexuality (r=27, p<0.01, N=154).

Quality of life among older adults: To examine which variables predict the quality of life among older adults, a stepwise regression was conducted. At first, the socio-demographic variables were included: age, gender, marital status (marital status variable was divided into two categories: have not a spouse/have a spouse), health status, economic status, years of education, level of religiosity. Then, all variables related to sexuality were included: frequency of sexual activity, satisfaction with sexual activity, difficulties in sexual activity, knowledge and attitudes toward sexuality in later life. The findings are presented in Table 5.

| Variables | b | SE | b | t | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Health status | 0.598 | 0.057 | 0.65 | 10.55*** | 0.423 |

| Step 2 | Health status | 0.454 | 0.059 | 0.493 | 7.74*** | 0.516 |

| Economic status | 0.345 | 0.064 | 0.344 | 5.40*** | ||

| Step 3 | Health status | 0.461 | 0.058 | 0.501 | 7.96*** | 0.531 |

| Economic status | 0.333 | 0.063 | 0.332 | 5.26*** | ||

| Level of religiosity | 0.185 | 0.084 | 0.123 | 2.19* | ||

| Step 4 | Health status | 421 | 0.056 | 0.458 | 7.46*** | 0.574 |

| Economic status | 0.288 | 0.062 | 0.287 | 4.66*** | ||

| Level of religiosity | 0.173 | 0.081 | 0.115 | 2.15* | ||

| Frequency of sexual activity | 0.184 | 0.048 | 0.22 | 3.86*** |

***p<0.001, *p<0.05

Table 5: Stepwise regression: Predictors of quality of life.

Data of Table 5 show that three socio-demographic variables entered the regression equation in the last step: health status, economic status, level of religiosity, and also the variable of frequency of sexual activity. That is, the better a person's health and economic situation, the more religious he is, and the more sexual activity he has, the higher his quality of life. These variables explained 57.4% of the explained variance in quality of life.

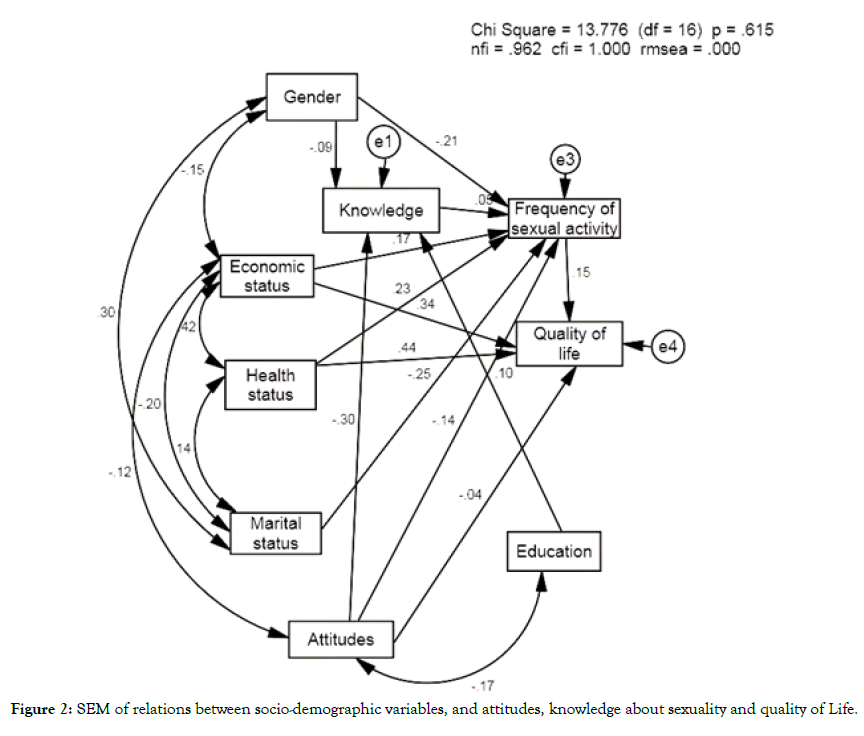

Finally, to describe the relations between socio-demographic variables, and attitudes, knowledge about sexuality and quality of life, a summary model based on Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was conducted (Figure 2).

Figure 2. SEM of relations between socio-demographic variables, and attitudes, knowledge about sexuality and quality of Life.

The model shows that the calculated goodness-of-fit measures were compatible with the data (χ2=13.77, p=0.615, nfi=0.962, cfi=1.000, RMSEA=0.000). The model indicates that permissive attitudes are related to knowledge about sexuality, and permissive attitudes are related to more frequent sexual activity. The variables: Frequency of sexual activity, good health status, and good economic status are related to the quality of life. In addition, the results revealed that marital status and gender are related to the frequency of sexual activity; that is, a woman has less sexual activity, and those who live with a spouse have more sexual activity.

Discussion

There has been little research on current attitudes and knowledge towards later life sexuality and sexual activity from the point of view of Israeli older adults. This study attempts to examine this neglected area and extend research by examining the attitudes, knowledge, and sexual activity of older adults, and the relationship these have to their quality of life.

The descriptive results in our study indicated that the older adults showed a moderate level of knowledge and permissive attitudes toward sexuality in later life. About half of the participants reported high and very high satisfaction with their sexual activity. These results correspond with previous studies, for example, Cybulski et al. found in Poland that the older adults were characterized by more open-minded attitudes, as opposed to the level of their knowledge [33]. In general, the older adults were characterized by moderate knowledge and attitudes to the sexuality of older people and average level of sexual satisfaction. However, a study conducted in Korea Park et al. indicates that the average score of sexual knowledge was below the median, and the average score on sexual attitude was above the median [7].

According to previous studies, older adults continue to engage in sexual activities even in later life [1,3,4,9,37]. Indeed, in our study we found that most of the participants have sexual activity, and most of them have full sex. Similar to other studies, the reasons for not having sexual activity indicated by the participants in our study included: lack of spouse, especially among women [2,3] and health problems or lack of interest [2,4,14-17]. Only few (5.2%) older adults in our study reported the nature of the sexual activity as mostly hugging and kissing. It might be that physical intimacy through cuddling and ‘touching’ exists when there are physical limitations that prevent full sexual intercourse [37].

The finding that most participants do not share concerns with a professional therapist about their sexuality is not surprising. Previous studies also found that sexual problems and sexual dysfunctions are frequent among older adults but are infrequently discussed with physicians; only a few older adults seek medical care [3,35,44]. It can be assumed older people are ashamed or felt uncomfortable talking about sex, and sharing this issue with professionals, and maybe they prevent from asking their advice and help. However, similar to the findings of Gott et al. we also found that the more difficulty the older adult has in maintaining sexual activity, the more he shares his concerns about sexuality with a professional [37]. Nonetheless, it is interesting that according to David study, Jewish religious older people turn to their rabbi for advice [24]. We did not include a question about consultation with a rabbi in our research. However, our study included a small percentage of religious participants. It is possible that the questions were too intrusive for them, even though the answers were sent via the Internet.

The findings reflected in the SEM model that permissive attitudes are related to knowledge about sexuality, and permissive attitudes are related to more sexual activity in later life are in line with previous studies [2,6-10]. For the older adults who have sexual activity regularly or frequently, the better their quality of life is, and frequency of sexual activity was also found as a predictor variable of the quality of life in later life. According to the mediation model, it was also found that sexual activity indicated a mediating effect on the relationship between attitudes towards older adults’ sexuality and quality of life. These results are consistent with previous findings [1,3,4,6,18,27-31]. Similar to the findings by Cybulski we found a positive relationship between attitudes toward sexuality and sexual satisfaction [33]. In addition, the finding that 'the more satisfying the sexual activity, the higher the quality of life' was supported by other studies [2,32].

With regard to the socio-demographic variables, the regression equation and the SEM model show that the health status and frequency of sexual activity were predictors of quality of life. The frequency of sexual behaviors was a significant predictor of quality of life also in previous study [26]. These findings are understandable in light of the health problems characteristic of the older population which cause sexual dysfunction among both men and women [2,4,14-17]. Because declining sexual function affects quality of life, physicians should offer patients information about evaluation and treatment Camacho et al. [45].

Consistent with previous studies [1,8-9], the current study found that the more educated the person is and the more knowledge about sexuality he has, the more permissive his attitudes toward sexuality are. It was also found that the more educated the person, the greater the frequency of having sexual activity. The explanation for these findings is that older adults with a high level of knowledge about sexuality better understand the physiological changes related to the aging process. Maybe educated people would search for a medical or other solution for their sexual problems, and can maintain a satisfying sexual activity leading to improved quality of life [7,9,10].

With regard to economic status, previous studies found high income related to higher level of sexual desire, positive attitudes toward sexuality, and greater sexual knowledge [6,9] Although our study found no correlation with knowledge, it was found, similar to the other studies, that the better the older adults' economic status, the more permissive attitudes toward sexuality are, the more frequent sexual activity is, and the higher the quality of life is.

Contrary to our hypothesis, no correlations and no differences were found in these variables (attitudes, knowledge, and frequency of sexual activity) with the age of the participants. This can be explained in accordance with the conclusion drawn by Lindau et al. [3,4] whereby sexual activity continues with aging unless the older person has health problems which affect sexual functioning [3,4].

Similar to other studies we found that men and older adults who have a relationship with a spouse have a higher frequency of sexual activity than women and older adults who do not have a spouse [3,4,9,19,21,34]. It seems that the relationship between these variables (gender and marital status) can explain the findings, as Lindau et al. maintained, that women are less likely than men to have a spousal or other intimate relationship, and to be sexually active [3,46,47].

Limitations and Future Research

The results of our studies should be interpreted in light of their limitations. The sample includes only Jews in Israel, and therefore it is difficult to generalize the findings. Hence, in light of the diverse ethnic, religious, and cultural composition of Israeli society, it would be worthwhile to include a broader representation of population groups in future studies (e.g., Jews from different ethnic backgrounds, Arab-Israelis, Druze-Israeli, and Bedouin-Israelis). It is also worthwhile to examine the older adult populations living in a nursing home and assisted living facility. Further research should add a focus on the unique concerns of LGBT older adults' sexuality, and include open-ended questions as well.

Despite these limitations, the central uniqueness of this study is the population it targets, Israeli older adults, and thus we attained more information about older adults' sexual attitudes and behavior in Israel. It can be concluded that sexuality among older adults in Israeli society is no different from other societies and cultures.

Conclusions

The practical recommendations are aimed primarily at professionals working with the older adult population. Since the main conclusion of this study, is that sexuality is very important and contributes to the quality of life of adults, educational programs should be designed for the older adults themselves and for professionals as well. Education should emphasize the benefits of older adults' sexuality; provide knowledge of current sexual behavior patterns, and the biological and psychosocial aspects of sexuality. Moreover, the older adults should be encouraged to seek help in the event that problems arise.

REFERENCES

- Beckman N, Waern M, Gustafson D, Skoog I. Secular trends in self-reported sexual activity and satisfaction in Swedish 70 year olds: Cross sectional survey of four populations, 1971-2001. BMJ. 2008; 337: 151-154.

- De Lamater JD. Sexual expression in later life: A Review and synthesis. J Sex Res. 2012; 49(2): 125-141.

- Lindau ST, Schumm L, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357: 762-774.

- Lindau ST, Gavrilova N. Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: Evidence from two US population based cross sectional surveys of ageing. BMJ. 2010; 340: 810-821.

- Santos-Iglesias P, Byers ES, Moglia R. Sexual well-being of older men and women. Can J Hum Sex. 2016; 25(2): 86-98.

- Papaharitou S, Nakopoulou E, Kirana P, Giaglis G, Moraitou M, Hatzichristou D. Factors associated with sexuality in later life: An exploratory study in a group of Greek married older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;46(2): 191-201.

- Park H, Kang SJ, Park S. Sexual knowledge, sexual attitude, and life satisfaction among Korean older adults: Implications for educational programs. Sexuality and Disability. 2016; 34(4): 455-468.

- Wang T, Lu C, Chen I, Yu S. Sexual knowledge, attitudes and activity of older people in Taipei, Taiwan. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(4): 443-450.

- De Lamater JD, Sill M. Sexual desire in later life. J Sex Res. 2005;42(2): 138-149.

- Penhollow TM, Young M, Denny G. Predictors of quality of life, sex intercourse, and sexual satisfaction among active older adults. Am J Health Educ. 2009; 40(1): 14-22.

- De Lamater JD, Moorman S. Sexual behavior in later life. J Aging Health. 2007; 19(6): 921-945.

- Forbes MK, Eaton NR, Krueger RF. Sexual quality of life and aging: A prospective study of a nationally representative sample. J Sex Res. 2017;54(2): 137-148.

- Træen B, Štulhofer A, Jurin T, Hald GM. Seventy-five years old and still going strong: Stability and change in sexual interest and sexual enjoyment in elderly men and women across Europe. Int J Sex Health. 2018.

- Ambler DR, Beiber EJ, Diamond MP. Sexual function in elderly women: A review of current literature. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(1):16-27.

- Karraker A, DeLamater J, Schwartz C. Sexual frequency decline from midlife to later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011; 66B(4): 502-512.

- Palacios-Ceña D, Martinez-Piedrola RM, Peres-de-Heredia M, Huertas-Hotas E, Carrasco-Garrido P, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C. Expressing sexuality in nursing homes. The experience of older women: A qualitative study. Geriatric Nursing.2016; 37(6): 470-477.

- Dominguez LJ, Barbagallo M. Ageing and sexuality. Eur Geriatr Med. 2016;7(6): 512-518.

- Laumann EO, Das A, Waite SL. Sexual dysfunctuon among older adults: Prevalence and risk factors from nationally representative U.S. probability sample of men and women 57-85 years of age prevalence. J Sex Med. 2008;5(10): 2300-2311.

- Bauer M, Mcauliffe L, Nay R, Chenco C. Sexuality in older adults: Effect of an education intervention on attitudes and beliefs of residential aged care staff. Edu Gerontol. 2013;39(2): 82-91.

- Kasif T, Band-Winterstein T. Older widow`s perspectives on sexuality: A life course perspective. J Aging Stud. 2017;41: 1-9.

- Waite LJ, Iveniuk J, Laumann EO, McClintock M. Sexuality in older couples: Individual and dyadic characteristics. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46(2): 605-618.

- Clarke LH. Older women and sexuality: Experiences in marital relationships. Journal of Aging Studies. 2017. 41: 1-9.

- Iveniuk J, O’Muircheartaigh C, Cagney KA. Religious influence on older Americans’ sexual Lives: A nationally-representative profile. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(1): 121-131.

- David BE, Weitzman GA. Sexuality in advanced age in Jewish thought and law. J Sex Marital Ther.2015;41(1): 39-48.

- World Association for Sexual Health. Sexual Health for the Millennium. A Declaration and Technical Document. 2008.

- Flyne TJ, Gow AJ. Examining associations between sexual behaviours and quality of life in older adults. Age Ageing. 2015;44(5): 823-828.

- Ginsberg TB, Pomerantz SC, Kramer-Feeley V. Sexuality in older adults: Behaviors and preferences. Age Ageing. 2005;34(5):475-480.

- Johnson C, Knight C, Alderman N. Challenges associated with the definition and assessment of inappropriate sexual behavior amongst individuals with an acquired neurological impairment. Brain Injury. 2006; 20(7): 687-693.

- Lochlainn MN, Kenny RA. Sexual activity and aging. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8): 565-572.

- Taylor A, Gosney MA. Sexuality in older age: Essential considerations for healthcare professionals. Age Ageing. 2011;40(5): 538-543.

- Wright H, Jenks RA. Sex on brain! Associatations between sexual activity and cognitive function in older age. Age Ageing. 2016;45(2): 313-317.

- McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Jaramillo SA, Legault C, Freund KM, Cochrane BB, Manson JE, et al. Corollaries of sexual satisfaction among sexually active postmenopausal women in the women's health initiative: Observational study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12): 2000-2009.

- Cybulski M, Cybulski L, Krajewska-Kulak E, Orzechowska M, Cwalina U, Jasinski M. Sexual quality of life, sexual knowledge, and attitudes of older adults on the example of inhabitants over 60s of Bialystok, Poland. Front Psychol. 2018;9: 483-492.

- Shuyan Y, Yan E. Demographic and psychosocial correlates of sexual activity in older Chinese people. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(5): 672-681.

- Nicolosi A, Buvat J, Glasser DB, Hartmann U, Laumann EO, Gingell C, et al. Sexual behavior, sexual dysfunctions and related help seeking patterns in middle-aged and elderly Europeans: The global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. World J Urol.2006;24(4): 423-428.

- Moreira ED, Glasser DB, King R, Duarte FG, Gingell C. The global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors investigators group. Sexual difficulties and help-seeking among mature adults in Australia: Results from the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviours. Sexual Health. 2008;5(3): 227-234.

- Gott M, Hinchliff S. How important is sex in later life? The views of older people. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(8): 1617–1628.

- Central Bureau of Statistics (2018). https://www.cbs.gov.il/EN/Pages/default.aspx

- Gewirtz-Meydan A, Ayalon L. Why do older adults have sex? Approach and avoidance sexual motives among older women and men. J Sex Res. 2018.

- Ayalon L, Gewirtz-Meydan A, Levkovich L. Older adults’ coping strategies with changes in sexual functioning: Results from qualitative research. J Sex Med. 2019;16(1): 52-60.

- White CB. A scale for the assessment of attitudes and knowledge regarding sexuality in the aged. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1982;11(6): 491-502.

- The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551-558.

- Ben Ya'acov Y, Amir M. Subjective quality of life: Definition and measurement according to the World Health Organization. Gerontology. 2001;28(3): 155-168.

- Pascoal EL, Slater M, Guiang C. Discussing sexual health with aging patients in primary care: Exploratory findings at a Canadian urban academic hospital. Can J Hum Sex. 2017;26(3): 226-237.

- Camacho ME, Reyes-Ortiz CA. Sexual dysfunction in the elderly: Age or disease? Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(1): 52-56.

- Bell S, Reissing ED. Sexual well-being in old women: The relevance of sexual excitation and sexual inhibition. J Sex Res. 2017;54(9): 1153-1165.

- Bouman WP, Kleinplatz PJ. Moving towards understanding greater diversity and fluidity of sexual expression of older people. Sex Relation Ther. 2015;30(1): 1-3.

Citation: Even-Zohar A, Werner S (2019) Older Adults and Sexuality in Israel: Knowledge, Attitudes, Sexual Activity and Quality of Life. J Aging Sci 7:209. DOI: 10.35248/2329-8847.19.7.209.

Copyright: © 2019 Even-Zohar A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.