Indexed In

- JournalTOCs

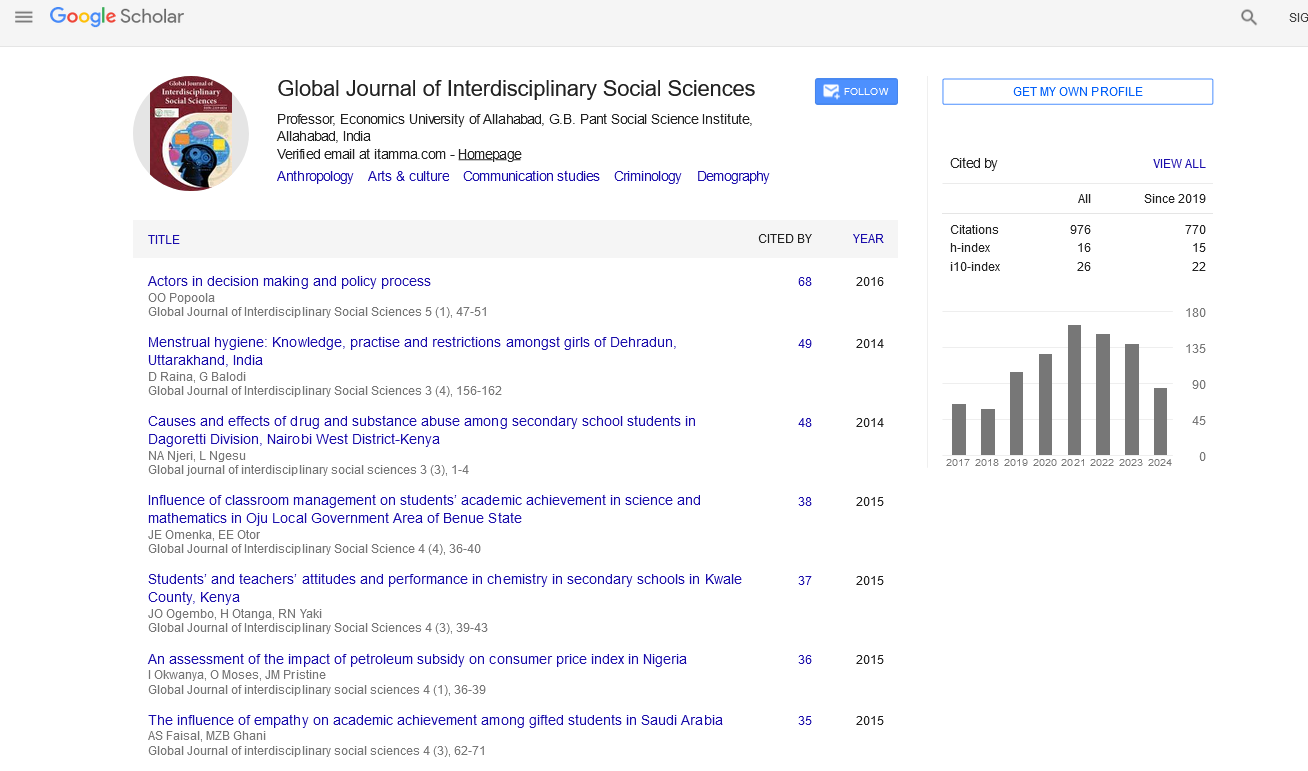

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Commentary - (2022) Volume 11, Issue 6

Impact of Migration on Mankind in Specific Regions of Asia and Europe

Marietta Albro*Received: 14-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. GJISS-22-18862; Editor assigned: 17-Nov-2022, Pre QC No. GJISS-22-18862(PQ); Reviewed: 02-Dec-2022, QC No. GJISS-22-18862; Revised: 09-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. GJISS-22-18862(R); Published: 16-Dec-2022, DOI: 10.35248/2319-8834.22.11.038

Description

The academic journey of archaeologist Peter Bellwood led him from England to teaching positions halfway across the globe, first in New Zealand and subsequently in Australia. He has spent more than 50 years researching how people colonised islands from Polynesia to Southeast Asia [1].

During his tour, Bellwood offers his own perspective on hotly debated subjects. But he says so when the facts at hand leaves a dispute unresolved [2]. Take a look at the first hominids. A brief mention is made of species that lived at least 4.4 million years ago or more and whose position as hominids is debatable, including Ardipithecus ramidus. Bellwood does not make a determination as to whether the discoveries are from early hominids or prehistoric apes. Instead, he concentrates on the African australopithecines, a group of upright but partially apelike creatures that are likely to have contained populations that developed into members of our own genus, Homo, between 2.5 million and 3 million years ago [3]. Bellwood makes a strong case for the idea that the development of larger brains in our ancestors was influenced by the production of stone tools by the last australopithecines, the earliest Homo groups, or both.

Bellwood devotes a lot of emphasis to how domestication and increased food production in Europe and Asia began after 9,000 years ago [4]. He expands on the claim made in his 2004 book First Farmers, which claims that as early cultivators' populations grew, they moved to other places in such large numbers that they dispersed major language families [5]. For instance, Bellwood argues that farmers from what is now Turkey introduced Indo- European languages into much of Europe shortly after approximately 8,000 years ago.

Conclusion

After Homo sapiens emerged, some 300,000 years ago in Africa, intercontinental migrations grew significantly. Bellwood views Neandertals, Denisovans, and H. sapiens as separate species that interbred in specific regions of Asia and Europe. He contends that Neandertals perished some 40,000 years ago as a result of mating with individuals from more numerous populations of H. sapiens, leaving a genetic imprint in modern humans. He does not, however, address the counterargument that Neandertals and other Homo populations at this period were too closely linked to have been separate species and that the evolution of modern humans was driven by occasional mating among these dispersed groups.

With a reconstruction of how early agricultural populations spread through East Asia and beyond, to Australia, a string of Pacific islands, and the Americas, Bellwood completes his evolutionary voyage. For instance, seafaring farmers from southern China and Taiwan brought Austronesian languages to Madagascar in the west and Polynesia in the east between 4,000 and 750 years ago. What exactly they did to pull off that amazing achievement is still a mystery.

References

- Hare-Duke L, Dening T, de Oliveira D, Milner K, Slade M. Conceptual framework for social connectedness in mental disorders: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. J. Affect. Disord.2019 ;15;245:188-99.

- Crepaz L, Huber C, Scheytt T. Governing arts through valuation: The role of the state as network actor in the European Capital of Culture 2010. Crit. Perspect.2016;1;37:35-50.

- Werner J, Wosch T, Gold C. Effectiveness of group music therapy versus recreational group singing for depressive symptoms of elderly nursing home residents: pragmatic trial. Aging & mental health. 2017;1;21(2):147-55.

- Daykin N, Mansfield L, Meads C, Julier G, Tomlinson A, Payne A, Grigsby Duffy L, Lane J, D’Innocenzo G, Burnett A, Kay T. What works for wellbeing? A systematic review of wellbeing outcomes for music and singing in adults. Persp. Pub heal. 2018;138(1):39-46.

- Dadswell A, Wilson C, Bungay H, Munn-Giddings C. The role of participatory arts in addressing the loneliness and social isolation of older people: a conceptual review of the literature. Journal of Arts & Communities. 2017;1;9(2):109-28.

Citation: Albro M (2022) Impact of Migration on Mankind in Specific Regions of Asia and Europe. Global J Interdiscipl Soc Sci. 11:038.

Copyright: © 2022 Albro M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.