Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

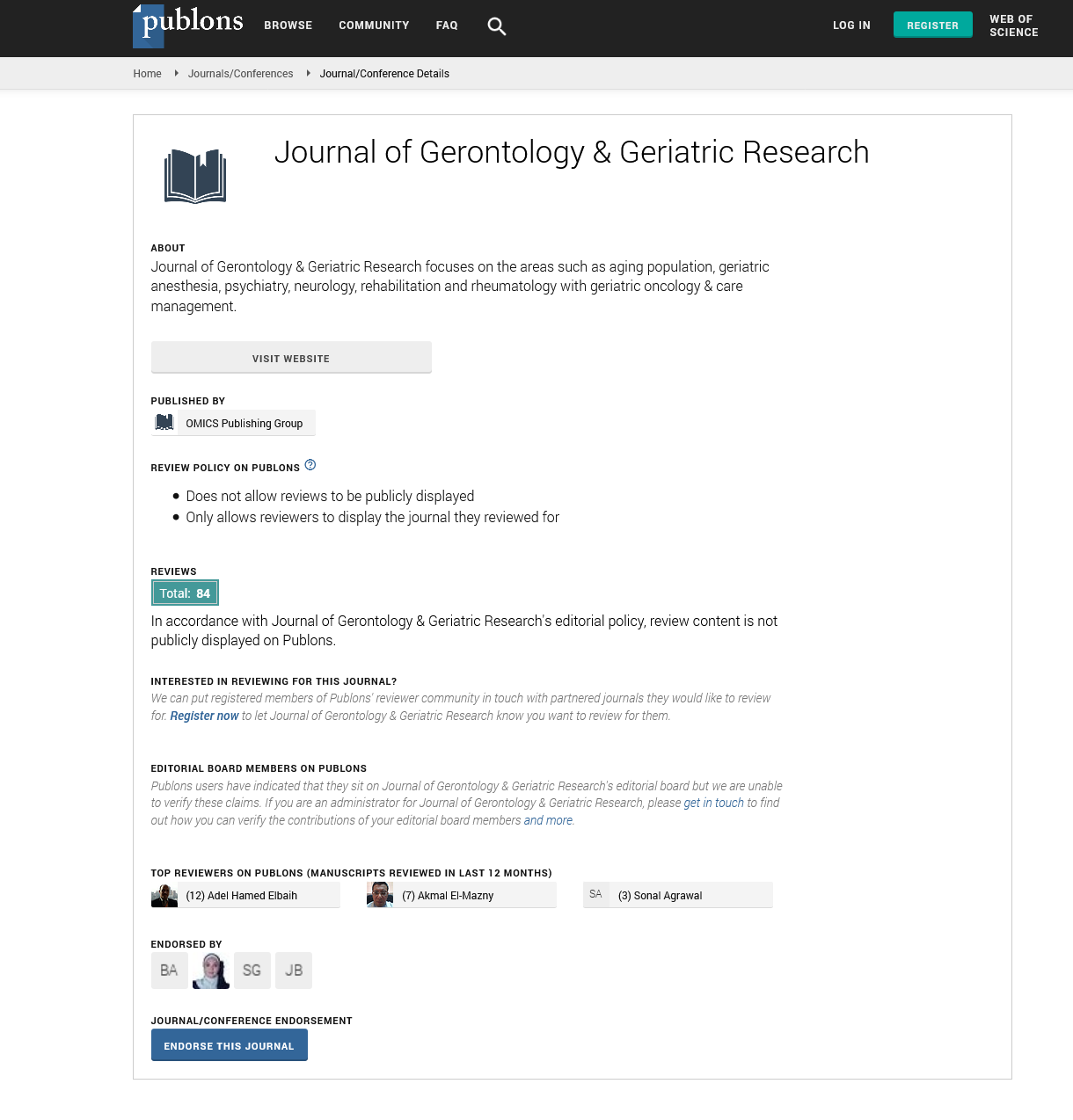

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Opinion - (2022) Volume 11, Issue 5

Measuring Quality of Care for Vulnerable Elders

Magda Almeida*Received: 05-May-2022, Manuscript No. jggr-22-17194; Editor assigned: 07-May-2022, Pre QC No. P-17194; Reviewed: 15-May-2022, QC No. Q-17194; Revised: 20-May-2022, Manuscript No. R-17194; Published: 25-May-2022, DOI: 10.35248/2167-7182.2022.11.613

Introduction

Outcome metrics represent the influence on the patient and show the final result of your improvement work, as well as whether it met the goal(s) specified. Reduced mortality, reduced length of stay, reduced hospital acquired infections, adverse occurrences or harm, reduced emergency admissions, and enhanced patient experience are examples of outcome measurements. Process measures indicate how your systems and processes operate together to get the desired result. For example, the amount of time a patient waits for a senior clinical review, whether a patient obtains particular levels of care or not, whether personnel wash their hands, incident recording and action, and whether patients are made informed of delays while waiting for an appointment. Processes and outcomes can both be used to assess care quality. Each strategy has advantages and disadvantages. We elected to assess the care of vulnerable elders using procedures rather than results, with the approval of the Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) Policy Advisory Committee. We did so because processes are a more efficient measure of quality; for most conditions, there is insufficient information in the medical record and a scarcity of validated models to adequately adjust outcomes for differences in case mix between providers; and, finally, processes of care are amenable to providerdirected action.These refer to the change's unanticipated and/or larger implications, which might be favourable or harmful. It's all about recognising them and seeking to quantify and/or mitigate their effects, if required. Monitoring emergency re-admission rates after measures to shorten length of stay is an example of a balancing measure [1,2].

Description

Outcome measures the "ultimate validators" of healthcare effectiveness and quality, although they can be difficult to define and involve time lags. Process metrics are critical in quality improvement because they describe whether clinical treatment has been "properly administered" or whether we are "performing the things we say we should do." They make the crucial link between behavioural changes and results from the standpoint of improvement. We identified vulnerable elders as people 65 and older who are at high risk of mortality or functional decline, and we developed a set of criteria to identify and measure individuals of that group. We didn't utilise utilisation statistics as a selection criterion because it's possible that picking people simply based on the health care they've received will leave out a significant portion of the population-those who are undertreated or underdiagnosed. Furthermore, we discovered that self-rated functional status was a more important predictor of functional decline and death than particular clinical diseases, based on a longitudinal analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. We devised a quick phone poll to determine age, self-reported health, physical limits, and functional constraints [3].

Over a two-year period, people who were recognised as vulnerable on the survey were more than four times as likely to die or exhibit functional impairment as those who were not. These criteria classified 32 present of a nationally representative sample of elders as vulnerable. A national panel of geriatrics experts developed the system by identifying the medical disorders that are common among older persons and contribute the most to morbidity, mortality, and functional decline; that can be quantified; and for which effective treatment or prevention techniques are available. Our advisory committee selected 22 subjects, including diseases, syndromes, physiological impairments, and clinical circumstances, for which quality-of-care indicators may be produced for this population, based on these criteria (see box, "ACOVE Topics"). According to them, The RAND team created quality-of-care markers for each condition. Processes or outcomes of care can be used to assess the quality of care. We picked process measurements because they are a more efficient measure of care quality and are more adaptable to change. However, high-quality research has only been used to support links between care practises and outcomes in a few cases, and those studies frequently omit vulnerable elderly. Our clinical experts evaluated the available data for its applicability to vulnerable elderly as we built our quality indicators [4,5].

Conclusion

We created instruments to extract medical information, interview patients or proxies, and review administrative data in order to implement the quality indicators in care settings. In two managed care plans, pilot testing of the majority of the indicators was accomplished. We investigated many considerations that might reduce the decision to apply a particular signal to the care of a particular patient, in awareness of the unique concerns of vulnerable elderly. Patient desires to avoid hospitalisation or surgery, as well as situations such as advanced dementia or a recorded grave diagnosis, were among these determinants (which might lead providers to withhold some otherwise indicated elements of care). In addition, when implementing the indicators, evaluators took into account local standards and care resources.

REFERENCES

- Waters HR. Measuring equity in access to health care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:599-612.

- Joling KJ. Quality indicators for community care for older people: A systematic review. PloS One. 2018;13:e0190298.

- Ferdousi R. Attitudes of nurses towards clinical information systems: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Inter Nursing Rev. 2021;68:59-66.

- Kusiak A. Innovation: The living laboratory perspective. Comp Aid Design Appl. 2007;4:863-876.

- Ballon P. The effectiveness of involving users in digital innovation: Measuring the impact of living labs. Telematics Inform. 2018;35:1201-1214.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Citation: Almeida M (2022) Measuring Quality of Care for Vulnerable Elders. J Gerontol Geriatr Res. 11:613.

Copyright: © 2022 Almeida M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.