Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- ResearchBible

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Mini Review - (2019) Volume 7, Issue 3

Is Successful Aging Declining with Age? The Age Profile of Objective, Subjective, and Preference-Based Measures of Successful Aging in Europe

Koen Decancq1* and Veerle Van Loon22Department of Sociology, University of Antwerp, Antwerpen, Belgium

Received: 19-Nov-2019 Published: 12-Dec-2019

Abstract

This note compares the age profile based on standard objective and subjective measures of successful aging with the age profile based on a novel preference-based measure proposed by Decancq et al. Using data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) for 2013, we find that the share of persons between 50 and 90 who are aging successfully in Europe declines with age according to the objective and preference-based measures of successful aging. At any point in the age distribution, the share of older persons who are aging successfully according to the preference-based measure is significantly larger than the share according to the objective measure. The subjective measure of successful aging, however, shows a remarkably stable age profile.

Keywords

Age profile; Successful aging; Cognitive functioning; Older people

Introduction

The rapid aging of our societies raises several policy challenges. When evaluating the design of aging policies that aim to increase the number of older persons who are aging successfully, policy makers and researchers need an operational yardstick to compare the degree of successful aging across people [1]. Comparing successful aging turns out to be a thorny issue, however (see, for instance, Decancq et al.) [2]. We illustrate this point by comparing age profiles using different approaches to measure successful aging to address the seemingly trivial question if the degree of successful aging was declining with age in 2013 in Europe.

Measures of Successful Aging

There is currently no consensus on how to define or measure successful aging [3,4]. One of the fundamental questions is who should assess when aging is considered to be successful [5,6]. Is this a matter for policy makers and researchers? Or should it be left to older persons themselves to evaluate whether they are aging successfully? Based on the answer to this question, the standard approaches to measure successful aging can be classified in two groups: objective and subjective measures [7].

Objective

Measures are based on external views of researchers or policy makers on what they regard to be successful aging. The biomedical model of Rowe et al. offers an example of the objective approach and is probably one of the most influential conceptualization of successful aging to date [8,9]. They consider a person to be aging successfully if she scores well than a threshold value on three criteria: freedom from disease and disability, high cognitive and physical functioning, and active engagement with life. According to this method, failing to reach the threshold value in one criterion cannot be compensated for by a good performance in another criterion. This noncompensatory perspective may not be shared by all older persons, however.

Subjective

Measures, on the other hand, rely on the direct judgments of older persons themselves with regards to how successfully they are aging. The pedigree of this approach goes back to the work of Havighurst (1961) who defined successful aging as having inner feelings of happiness and satisfaction with one’s present and past life [10].

According to this definition, successful aging can be measured on the basis of self-reported life satisfaction such that older persons with a high life satisfaction score are considered to be aging successfully while those with a low life satisfaction score are not. The subjective approach seems appealing because the older persons themselves determine what the relative importance of the different aspects of successful aging is and whether there can be compensation between them.

The tension between the objective and subjective approach is more than a mere theoretical concern about who should define successful aging. Strawbridge et al. for example, find great discrepancies in prevalence rates of successful aging when adopting an objective or subjective definition [11]. Decancq et al. show how both objective and subjective measures fail to pass a litmus test of respect for older persons’ preferences about what matters in their life [2].

In particular, they show that objective – but also subjective – measures may go against a unanimous agreement between two older persons on who of them is aging more successfully. The reason is that objective measures are constructed independently of older persons’ preferences and are therefore not necessarily consistent with their opinions. Subjective measures, on the other hand, not only capture the preferences of the older persons, but also other aspects such as their level of adaptation, their expectations, and idiosyncratic personality traits. This is bad news, especially for researchers and policy makers who try to make interpersonal comparisons of successful aging.

Decancq et al. propose therefore an alternative preference-based approach to the measurement of successful aging [2]. In the preference-based approach, older persons use their own preferences to compare their life situation to a fixed reference situation. If they consider themselves to be better off than this reference situation, they are considered to be aging successfully.

Conversely, if they prefer the threshold vector to their own life situation, they are considered not to be aging successfully. A preference-based measure of successful aging is consistent with older persons’ own idea about the ‘good life’ and passes the litmus test of respect for preferences in interpersonal comparisons [2]. This last feature is important for researchers who want to compare successful aging across people and for policy makers who want to give special attention to the worst-off older persons when designing and implementing aging policies.

This note illustrates an empirical implication of using different approaches to measure successful aging with respect to the seemly trivial question whether successful aging declines with age. More precisely, we compare age profiles based on standard objective and subjective measures of successful aging with the age profile based on the novel preference-based measure proposed by Decancq et al. [2]. An age profile presents for each age group the share of older people that is aging successfully.

As they are constructed with cross-sectional data, age profiles do not allow us to isolate the effect of age from cohort and time effects and, hence, have to be interpreted carefully (see Schilling for a discussion) [12]. Nevertheless, age profiles of successful aging are useful to visualize how successfully different age groups in a population are aging.

Implementation with Share

We use data from the fifth wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), which was collected in 2013. We restrict the sample to respondents between 50 and 90 years old who are living in one of the following European countries: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, and Sweden. Respondents for whom we did not possess all the necessary information to compute the three measures of successful aging, were left out of the sample. This leaves us with a total sample of 48,013 respondents.

The operationalization of the objective, subjective, and preference-based method to measure successful aging is identical to the one of Decancq et al. (all implementation details can be found there) [2]. Following the study by [9], the authors included five dimensions of successful aging in the objective measure: absence of disease and absence of disability, cognitive and physical functional capacity, and engagement with life. As discussed above, respondents are aging successfully when they score higher than a given threshold value in each of these dimensions. For the subjective approach, Decancq et al. follow Strawbridge et al. [2,11].

Respondents who report that their life satisfaction is higher or equal than 9 on a 10-point scale, are considered as aging successfully. The main empirical challenge for the preferencebased approach is to obtain information about older person’s preferences between the actual life situation and the fixed reference situation. Decancq et al. use a statistical regression model to estimate these preferences [2,13,14].

The model explains the answers of respondents to a life satisfaction question based on observable characteristics. With this model, the life satisfaction in the actual life situation and the fixed reference situation (that consists of the threshold value in each of the five dimensions of successful aging) can be predicted and compared. This model-based prediction considers only the outcomes in the five dimensions of successful aging and the preferences about their relative importance, but not the adaptation, expectations, and idiosyncratic personality traits of the respondents.

This is the main difference with the subjective approach. According to the preference-based approach, respondents for whom the predicted life satisfaction is higher in the actual life situation compared to the reference life situation are said to consider themselves to be better off than the reference situation, and are considered to be aging successfully.

Table 1 presents the share of the population between 50 and 90 in each country that is considered to be aging successfully according to the three methods. More people are considered to be aging successfully according to the preference-based measure compared to the other measures. Yet, we see considerable heterogeneity across countries and across methods.

| All Countries | Objective | Subjective | Preference-based |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30.7 | 27.8 | 46.3 | |

| Austria | 34.9 | 42.2 | 55.3 |

| Germany | 30.7 | 30.4 | 46.2 |

| Swden | 40.1 | 45.9 | 40.3 |

| Netherlands | 40.8 | 25.3 | 56.2 |

| Spain | 24.4 | 28.5 | 41 |

| Italy | 25.1 | 24.7 | 42.6 |

| France | 32.4 | 18.8 | 47.9 |

| Denmark | 43.4 | 54.8 | 43.6 |

| Switzerland | 49.5 | 45.3 | 68.2 |

| Belgium | 32.3 | 24.8 | 49.5 |

| Czech republic | 30.2 | 24.4 | 46.1 |

Table 1: Successful aging according to three measures in 2013 (Source: SHARE wave 5).

When comparing, for instance, France and Denmark, we see that a larger share of the French older persons are aging successfully according to the preference-based measure, while more Danish older persons are aging successfully according to the objective and subjective measures. Especially the subjective measure of successful aging shows a large difference between both countries with the measure being almost thrice as large in Denmark. These country averages mask considerable heterogeneity across age groups. In the next section, we therefore zoom in on this heterogeneity and consider the age profiles of successful aging according to the three methods (Table 1).

The Age Profile of Successful Aging

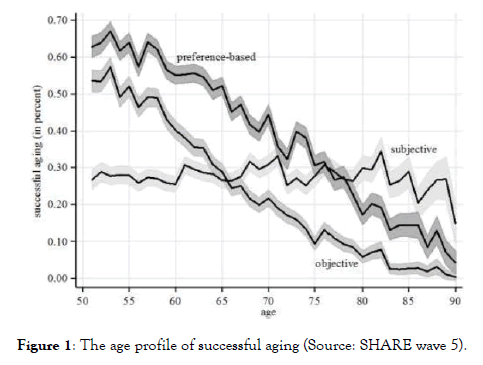

Figure 1 shows the age profile of successful aging according to the objective, subjective, and preference based measures and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. We see that the share of people who are aging successfully according to the objective and preference-based measures declines with age.

Figure 1. The age profile of successful aging (Source: SHARE wave 5).

While more than half of the sample is aging successfully at age 50 according to these measures, less than 10% of the sample is doing that at age 90. This finding is intuitive. Note, however, that the preference-based measure is consistently and significantly higher than the objective measure, especially in the age category between 60 and 80.

When looking at the subjective measure, however, we observe a totally different pattern. The subjective measure of successful aging shows a stable pattern that snakes around the level of 29% until the age of 80, after which it becomes less precisely estimated and starts to decline (Figure 1).

The remarkably stable level of the subjective successful aging measures has previously been referred to as the “satisfaction paradox” in the literature (see Baird et al. for a careful study using longitudinal data and Gana et al. for a discussion of the empirical findings on the satisfaction paradox) [15,16]. Underlying this stable level of successful aging are presumably several countervailing forces at play such as the process of aging itself, adaptation, and shifting expectations [17-19].

Discussion and Avenues for Further Research

This note illustrates how a simple almost trivial question about the age profile of successful aging leads to different empirical results based on the choice of measure of successful aging. When comparing, for example, the group of 82 year old persons in Figure 1 with the group of 60-year old persons, we see that the former, older, group maintains a significantly higher level of subjective successful aging compared to the younger group (p value of t test of the difference between the levels of subjective successful aging : p<0.0387), while the share of people in the younger group who consider themselves to be better off than a fixed reference situation (as indicated by the preference-based measure) is about three times as large (p value of t test of the difference between levels of preference-based successful aging: p<0.0001). How to compare the successful aging of both age groups is ultimately a value judgment about the role that adaptation, expectations, and idiosyncratic personality traits should play in these comparisons. While these aspects are deliberately not taken in account in the preference-based approach, they clearly affect the level of successful aging in the subjective approach.

Conclusion

Echoing the conclusion of Decancq et al. we argue that policy makers and researchers who want to compare the levels of successful aging across older persons with respect for their preferences should consider using the novel preference-based measure of successful aging. To be fair, the development of the preference-based approach is still in its infancy. Several avenues for further research are still open. First, the 7 statistical methods for estimating preferences should be further refined and improved. Ideally, a tailored and specific survey instrument should be designed that asks older persons to compare their own life situations with the fixed reference situation. Finally, important theoretical questions remain about the identification of the relevant preferences of older persons who suffer from dementia or cognitive decline.

REFERENCES

- Pruchno RA. Successful aging: Contentious past, productive future. Gerontology. 2015;55(1): 1-4.

- Decancq K, Michiels A. Measuring successful aging with respect for the preferences of older persons. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74(2): 364-372.

- Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(1): 6-20.

- Cosco TD, Prina AM, Perales J, Stephan BC, Brayne C. Lay perspectives of successful ageing: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6): 1-9.

- Bowling A, Dieppe P. What is successful ageing and who should define it? BMJ. 2005;331(7531): 1548-1551.

- Martinson M, Berridge C. Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. Gerontology. 2015;55(1): 58-69.

- Pruchno RA, Wilson-genderson M, Cartwright F. A two-factor model of successful aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65(6): 671-679.

- Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontology. 1997;37(4): 433-440.

- Hank K. How “successful” do older Europeans age? Findings from SHARE. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;66(2):230-236.

- Havighurst RJ. Successful Aging. Gerontology. 1961;1(1): 8-13.

- Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI, Cohen RD. Successful aging and well-being selfrated compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontology. 2002;42(6): 727-733.

- Schilling O. Development of life satisfaction in old age: another view on the paradox. Soc Indic Res. 2006:75(2): 241-271.

- Clark AE, Oswald AJ. A simple statistical method for measuring how life events affect happiness. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(6); 1139-1144.

- Decancq K, Schokkaert E. Beyond GDP: Using equivalent incomes to measure well-being in Europe. Social Indicators Research. 2016;126(1): 21-55.

- Baird BM, Lucas RE, Donnellan MB. Life satisfaction across the lifespan:Findings from two nationally representative panel studies. Soc Indic Res. 2010;99(2): 183-203.

- Gana K, Bailly N, Saada Y, Joulain M, Alaphilippe D. Does life satisfaction change in old age: Results from an 8-year longitudinal study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4): 540-552.

- Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes PB, Baltes MM (eds) Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences, Cambridge University Press, New York, USA, 1990; pp: 1-34.

- Carstensen LL, Fung H, Charles ST. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motiv Emot. 2003;27(2): 103-123.

- Martin P, Kelly N, Kahana B, Kahana E, Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, et al. Defining successful aging: A tangible or elusive concept? Gerontology. 2015;55(1): 14-25.

Citation: Decancq K, Van Loon V (2019) Is Successful Aging Declining with Age? The Age Profile of Objective, Subjective, and Preference-Based Measures of Successful Aging in Europe. J Aging Sci. 7: 215. Doi:10.35248/2329-8847.19.07.215.

Copyright: © 2019 Decancq K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.