Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- Academic Keys

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research - (2019) Volume 8, Issue 2

Importance of Prolidase Enzyme Activity and Serum Cytokeratin 18 Levels for Differential Diagnosis between Asymptomatic Hepatitis B Carriers and HBeAg Negative Chronic Hepatitis B Patients

Nimet Yılmaz*, Ayhan Balkan and Mehmet KorukReceived: 21-Jun-2019 Published: 12-Aug-2019, DOI: 10.35248/2167-0889.19.8.237

Abstract

Background: In this study, it was aimed to evaluate the relationship between the severity of necroinflammation in the liver and the stage of fibrosis and the serum levels of Serum Prolidase Activity (SPA) and Cytokeratin (CK)-18 in patients with active Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) and asymptomatic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) carriers.

Methods: Biochemical analyses, serological parameters associated with HBV and serum prolidase activity and CK-18 levels were measured in asymptomatic HBV carriers (n=65), active CHB patients (n=60) and healthy controls (n=27). Liver biopsies were performed on asymptomatic HBV carriers and active CHB patients.

Findings: SPA level was significantly higher in active CHB patients (819.92 ± 123.74 IU/L) compared to asymptomatic HBV carriers (732.99 ± 124.70 IU/L) and was higher in asymptomatic HBV carriers compared to healthy controls (529.4 ± 74.73 IU/L) (p=0.001). The diagnostic cut-off value of SPA level was found 751.15 U/L. When this cut-off value was taken to differentiate HBe-Ag negative CHB in asymptomatic HBV carriers, sensitivity and specificity of efficacy were 72% and 63% respectively (c-statistics: 0.707). A strong positive correlation was observed between serum prolidase level and the severity of fibrosis in asymptomatic HBV carriers (r=0.603, p=0.000). A positive correlation was determined between SPA level and Histological Activity Index (HAI) scores in patients with active CHB and asymptomatic HBV carriers. The serum CK-18 levels were significantly lower in the healthy control group when compared to the asymptomatic HBV carriers and active CHB patients (p=0.001).

Conclusion: Prolidase enzyme may be beneficial in differentiating asymptomatic HBV carriers from HBeAg-negative CHB patients when used in combination with ALT and HBV-DNA levels.

Introduction

A large population of Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) infection, which is one of the most widespread causes of chronic liver disease worldwide, consists of asymptomatic carriers [1]. Previously, it was considered that this Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) carriers are clinically asymptomatic since the virus is dormant in these patients and thus the risk of developing cirrhosis is low. However, it has been recently observed that the disease at the carrier stage is not dormant [2]. Because fibrotic activity has been found to be increased in patients with HBeAg negative CHB, it is important to discriminate between asymptomatic HBV carriers and patients with HBeAg-negative CHB [3]. This discrimination is being made by determining serum ALT and HBV-DNA levels and performing liver histopathology. Liver needle biopsy is an invasive and costly method. Serum ALT and HBV DNA levels are a part of analyses that are used for estimating the stage of chronic hepatitis but their ideal limit values and certainty have not been clear yet [4].

Prolidase is an enzyme that breaks down iminodipeptides generated after collagen destruction and is a rate-limiting enzyme in the last stage of collagen degradation pathway. Increased production and destruction of collagen causes an increase in Serum Prolidase Activity (SPA) [5]. Several studies have demonstrated that SPA is a useful marker for evaluating liver fibrosis and SPA level also increases in parallel with higher stages of fibrosis [6-9]. Therefore, SPA level has been considered to be a useful marker in patients with chronic liver disease for whom long-term follow up is important [10].

Cytokeratin 18 (CK-18), however, is the first cytokeratin expressed during the embryogenesis [11]. It is found in the liver, pancreas, intestines and epithelial tissues. CK-18 is the major intermediate filament of the liver cytoskeleton and is the main substrate of caspases that occur during hepatic apoptosis [12]. The study by Gonzalez et al. revealed that CK-18 levels increased in chronic viral hepatitis, hepatosteatosis, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis and cholestasis [13].

In the present study, based on these data, it was aimed to evaluate the relationship between the severity of necroinflammation in the liver and the stage of fibrosis and the serum levels of SPA and CK- 18 in patients with chronic active CHB and asymptomatic HBV carriers.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The study was performed at the Gaziantep University Medical Faculty Hospital between September 2011 and June 2012. A total of 65 asymptomatic HBV carriers, 60 patients with CHB who were being followed up in the Gastroenterology Outpatient Clinic for three years and 27 healthy volunteers were enrolled in the study. The written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2008 and with the approval numbered 07.2011/39 of the University of Gaziantep Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

The patients with positive anti-HCV, anti-HDV and anti-HIV antibodies and those with positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA), Anti-Smooth Muscle Antibodies (ASMA) and Anti-Mitochondrial Antibodies (AMA) were excluded. Moreover, patients who had received antiviral therapy or immunomodulatory therapy within the last 12 months, those with decompensated liver cirrhosis, those with cancer and those with inadequate liver biopsy were also excluded. Abdominal ultrasonography was performed on all patients. Body Mass Index (BMI) of the patients was calculated. After documenting their medical history in detail and conducting a comprehensive physical examination, Complete Blood Count (CBC), serum hepatic function tests (Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), Gamma Glutamyl Transferase (GGT), total bilirubin, direct bilirubin and albumin)], triglyceride level, total cholesterol level, Fasting Blood Glucose (FBG) level, presence of anti-HIV, anti-HCV, anti-Delta, HBsAg, anti HBs, HBeAg, anti-HBe, anti HBc IgM and anti-HBcIgG antibodies, HBV-DNA, SPA and CK-18 levels were analyzed. The characteristics of asymptomatic HBV carriers were defined as follows: the presence of HBsAg in the serum for >6 months, HBeAg negative, anti-HBe positive, HBV DNA level of <2000 IU/mL and persistently normal ALT/AST levels (<40 U/L). Asymptomatic HBV carriers were followed up for at least one year by analyzing their HBV DNA and ALT levels every three months. From the group of patients with documented evidence of HBsAg positivity for >6 months and HBeAg (−) or (+), those with normal (<40 U/L) or high ALT levels and an HBV-DNA level of >2000 IU/mL were considered to have CHB infection.

Healthy control subjects

SPA and CK-18 levels were determined using the serum samples of 27 normal healthy individuals. ANA, AMA, ASMA, HBsAg, anti-HCV, anti-HIV and anti-HDV results of the control group were negative and hepatic function tests, FBG, total cholesterol, triglyceride and CBC values were within normal ranges.

Serum prolidase activity (SPA) analysis

Collection of blood samples and liver biopsy were performed on the same day for the patients. The blood samples were kept at room temperature for 30–60 min, centrifuged at 3000–5000 rpm for 10–15 min to obtain the serum samples and stored in a freezer at -80°C for SPA analysis. Approximately six months later, the serum samples were removed from the freezer. SPA level was measured using ELISA as described earlier in the literature [6].

Cytokeratin 18 (CK-18) analysis

The CK-18 M30 fragment was measured with the method suggested by Ueno et al. [12]. This method was used to measure the specific apoptosis of the CK-18 positive cells and quantitatively measure the neoepitope (M30) associated with apoptosis in the C terminal part (aminoacid 387-396) of CK-18. The M30-Apoptosense was used by the ELISA kit (PEVIVA, Alexis, Grünwald, Germany) to quantitatively measure the CK-18 levels. All tests for M30 were performed as two copies and the measurement results were calculated using a microplate reader.

Histological examination

Both asymptomatic HBV carriers and patients with CHB underwent ultrasonography-guided percutaneous biopsy of the right lobe of the liver. A quick-cut and 16-Gauge cutting needle (GALLINI, Italy) was used for this procedure. The lengths of the biopsy samples were 1.5–2.0 cm with 7 or more available portal areas. Liver biopsy samples were examined in a pathology laboratory by a single pathologist. Histopathological examination was performed in accordance with the modified Ishak scoring system. It was agreed that samples with a Histological Activity Index (HAI) of <4 and a fibrosis score of <2 would be considered as a mild histological lesion; HAI=4–8 and fibrosis score=2–3 would be considered as a moderate histological lesion; and HAI >8 and fibrosis score >3 would be considered as severe histological lesion.

Serology

In all the patients, anti-HCV, anti-HDV, anti-HIV, HBsAg, HBeAg and anti-HBe tests were performed using ELISA, whereas HBVDNA tests were performed using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Amplicor HBV Monitor test, Roche Diagnostic Systems, Inc., Branchburg, NJ) (sensitivity 60 IU/mL).

Ethics committee approval

This study was conducted after receiving the approval of Gaziantep University Medical Faculty Clinical Researches Local Ethics Committee (Date: 07/2011, Decision No: 39).

Statistical analysis

Using the SPSS-13 program, the significance test (Student’s t-test) was used for the difference between two averages during the comparison of SPA and SK-18 levels in terms of two different groups, the Mann Whitney U test was used for the variables without normal distribution and the multi-factor analysis of variance (oneway ANOVA) was used in the comparison of more than two groups. The Spearman’s rho test was used to determine the relationship between SPA, CK-18 and other parameters. Using the CK18 and SPA, the cut off value was determined with the ROC analysis to make the right diagnosis in HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B patients. The mean ± standard deviation values were given as descriptive statistics. The p-value was accepted as significant when it was ≤ 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Demographic information and laboratory results of 152 cases were analyzed. The cases were divided into three groups: healthy volunteers (n=27), asymptomatic HBV carriers, (n=65) and active CHB patients (n=60). Liver biopsy and histopathological examinations were performed in asymptomatic HBV carriers and patients with CHB (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographics.

| Patient Characteristics | Healthy (n=27) | Asymptomatic HBV carriers (n=65) | Chronic hepatitis B (n=60) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 36.81± 10.70 | 34.38 ± 9.64 | 35.23± 12.22 | ns. |

| Gender (F/M) | 16-Nov | 34/31 | 28/32 | ns. |

| VKI, (kg/m²) | 25.00 ± 1.83 | 23.26 ± 2.07 | 24.43± 3.53 | 0.001a,b |

| FBG (mg/dL) | 88.70 ± 11.49 | 90.93 ± 12.08 | 91.21 ± 13.63 | ns. |

| Urea, mg/dL | 24.74 ± 6.23 | 24.09 ± 6.23 | 26.16 ± 7.87 | ns. |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.55 ± 0.21 | 0.68 ± 0.11 | 0.69 ± 0.17 | 0.001a,c |

| WBC (×10³ /µL) | 6.53 ± 1.6 | 6.86 ± 1.75 | 6.83 ± 1.53 | ns. |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.11 ± 1.45 | 13.75 ± 1.74 | 14.28 ± 1.79 | ns. |

| Hematocrit (%) | 41.74 ± 3.63 | 41.43 ± 4.37 | 43.08 ± 4.76 | ns. |

| Platelet (×10³ /µL) | 221.40 ± 44.08 | 235.60 ± 60.22 | 230.05 ± 59.46 | ns. |

| ALT (U/L) | 29.33 ± 15.23 | 24.78 ± 12.20 | 65.10 ± 65.15 | 0.001,b,c |

| AST (U/L) | 21.18 ± 5.83 | 21.64 ± 7.02 | 41.10 ± 35.80 | 0.001b,c |

| ALP (U/L) | 48.88 ± 25.48 | 76.47 ± 29.42 | 86.25 ± 31.53 | 0.001a,c |

| GGT (U/L) | 27.11 ± 12.40 | 22.55 ± 12.52 | 37.96 ± 28.25 | 0.001b,c |

| T. bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.55 ± 0.24 | 0.64 ± 0.38 | 0.72 ± 0.51 | ns. |

| D. bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.25 ± 0.16 | 0.25 ± 0.19 | 0.30 ± 0.33 | ns. |

| Albumin, (g/dL) | 4.18 ± 0.31 | 3.94 ± 0.42 | 3.96 ± 0.36 | 0.001a,c |

| PT (sn.) | 12.07 ± 0.82 | 12.86 ± 1.08 | 13.13 ± 1.08 | 0.001a,c |

| AFP, IU/mL | 3.14 ± 2.00 | 3.06 ± 2.09 | 3.59 ± 2.10 | ns. |

| HBV DNA (×10³ IU/mL) | 0.561 ± 0.554 | 31256 ± 888088 | 0.001 | |

| Serum Prolidase U/L | 529.40± 74.73 | 732.99 ± 124.70 | 819.92 ± 123.74 | 0.001a,b |

| Serum CK-18, U/L | 121.99 ± 40.44 | 238.77 ± 107.91 | 229.54 ± 92.81 | 0.001a,c |

ns.: Not significant; AFP: Alpha-Fetoprotein; FBG: Fasting Blood Glucose; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferas; GGT: Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase; HBV: Hepatitis B Virus; PT: Prothrombin Time; VKI: Body Mass Index. a=Comparison between healthy volunteers and inactive HBV carriers. b= Comparison between inactive HBV carriers and chronic HBV patients. c= Comparison between healthy volunteers and chronic HBV patients.

There was no difference in asymptomatic HBV carriers and active CHB patients, in the abdominal ultrasonography in terms of steatosis grade (p>0.05). HBV-DNA levels were significantly lower in asymptomatic HBV carriers compared to active CHB patients (p=0.001). AST and ALT levels were significantly higher in active CHB patients than in asymptomatic HBV carriers and in healthy controls (p=0.001) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2: HBV DNA, prolidase, CK18, histopathological and ultrasonographic findings of asymptomatic HBV carriers and CHB patients.

| Results | Asymptomatic HBV carriers (n=65) | Chronic hepatitis B (n=60) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBV DNA (×10³ IU/mL) | 0,561 ± 0.554 | 31256 ± 888088 | 0.001 |

| Serum Prolidase U/L | 732.99 ± 124.70 | 819.92 ± 123.74 | 0.001 |

| Serum CK18, U/L | 238.77 ± 107.91 | 229.54 ± 92.81 | 0.61 |

| Hepatosteatosis Grading (US) (N/G1/G2/G3) | 49/10/6/0 | 49/8/3/0 | ns. |

| HAI, (mild/medium/severe) | 52/13/0 | 22/36/2 | 0.001 |

| Fibrosis, (mild /medium /severe) | 55/9/1 | 8/42/10 | 0.001 |

| Ground glass (+/-) | Dec-53 | 14/46 | ns. |

| Hydropic degeneration (+/-) | May-60 | Apr-54 | ns. |

ns.: Not significant; AFP: Alpha-Fetoprotein; FBG: Fasting Blood Glucose; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; GGT: Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase; HBV: Hepatitis B Virus, PT: Prothrombin Time; VKI: Body Mass Index; CK18: Cytokeratin-18; G: Grade; HAI: Histologic Activity Index, US: Ultrasonography.

SPA findings

SPA levels were significantly higher in active CHB patients compared to those in asymptomatic HBV carriers and significantly higher in asymptomatic HBV carriers compared to those in healthy controls (p=0.001) (Table 1).

Liver histology in asymptomatic HBV carriers and patients with chronic hepatitis B

The number of patients with moderate and severe HAI scores (≥ 4/18) was 13 (20%), and the number of patients with moderate and severe fibrosis (≥ 2/6) was 10 (15%) in asymptomatic HBV carriers. SPA level was significantly higher in asymptomatic carriers with moderate-to-severe fibrosis compared to those with mild fibrosis (p=0.001) (Table 3). The number of patients with moderate and severe HAI scores (≥ 4/18) was 38 (63%) and the number of patients with moderate and severe fibrosis (≥ 2/6) was 52 (86%) in active CHB patients. SPA level was significantly higher in active CHB patients with moderate-to-severe fibrosis compared to those with mild fibrosis (p=0.001).

Table 3: Comparison of asymptomatic HBV carriers according to their histopathological results.

| Histopathologic stage of the disease | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Results | Mild (n=55) (Mean ± SD.) | Medium/severe (n=10) (Mean ± SD.) | p value |

| HBV DNA (×10³ IU/ml) | 0.569 ± 0.551 | 0.520±0.597 | ns. |

| Prolidase, (U/L) | 710.30±110.82 | 857.83 ± 128.18 | 0.001 |

| Serum CK18 (U/L) | 242.68 ± 114.11 | 214.93 ± 62.91 | ns. |

| Hepatosteatosis Grading (US) (N/G1/G2/G3) | 41 / 9 /5 / 0 | 8 / 1 / 1 / 0 | ns. |

| HAI (mean ± SD) | 2.25 ± 1.07 | 3.90 ± 0.73 | 0.001 |

| Ground glass (+/-) | Oct-45 | 02-Aug | ns. |

| Hydropic degeneration (+/-) | Apr-51 | 01-Sep | ns. |

ns.: Not significant; CK18: Cytokeratin-18; G: Grade; HAI: Histologic Activity Index., US: Ultrasonography

The relationship between Serum CK-18 M30 levels and histopathological findings

There was no significant relationship between serum CK-18 levels and ALT, HBV DNA and liver fibrosis severity in asymptomatic HBV carriers and CHB patients (p>0.05) (Table 2). In patients with active CHB, however, there was a weak positive correlation between serum CK-18 levels and HAI scores (r=0.372, p=0.003).

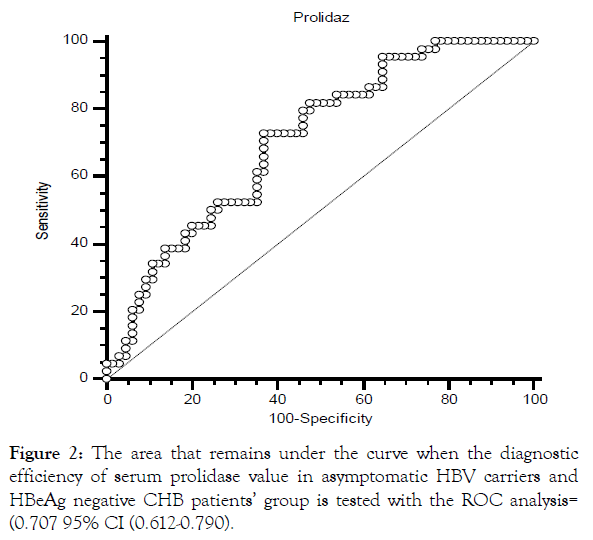

In the present study, the diagnosis efficacy of SPA and CK18 levels in differentiating asymptomatic HBV carriers from HBeAgnegative CHB patients was also investigated. ROC (receiver operating characteristic) analysis was performed. As a result, it was determined that the CK18 levels had poor diagnostic efficiency [0.521, 95% CI (0.423-0.617)].

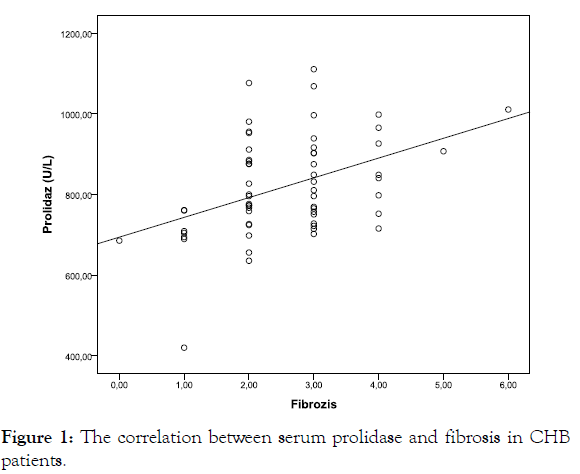

Correlation between serum markers of liver inflammation and histopathological findings with SPA

Correlation analyses were performed SPA levels, levels of ALT and HBV-DNA; HAI; and the severity of fibrosis in asymptomatic HBV carriers and CHB patients in this study. A strong positive correlation was observed between SPA level and the severity of fibrosis in asymptomatic HBV carriers (r=0.603, p<0.001) (Figure 1). A moderately positive correlation was observed between SPA level and the severity of fibrosis in the active CHB patients (r=0.428, p=0.001).

Figure 1: The correlation between serum prolidase and fibrosis in CHB patients.

Effectivity of SPA in differentiating asymptomatic HBV carriers from patients with HBeAg- negative CHB

The patients with active CHB were divided into two groups as HBeAg- negative (n=45) and HBeAg positive (n=15).

The HBeAg-negative 110 patients were grouped as asymptomatic HBV carriers and HBeAg-negative active CHB patients. SPA level was significantly lower in asymptomatic HBV carriers (n=65) compared to that in HBeAg-negative CHB patients (n=45) (p=0.001) (Table 4). The diagnostic efficiency of serum SPA level was found to be strong in asymptomatic HBV carrier and HBeAg-negative CHB patient groups. The cut-off value of SPA level was determined as 751.15 U/L by this analysis [OR: 0.707, 95% CI (0.612-0.790)]. In our study, 45 patients with HBeAg-negative CHB were divided into two groups according to low and high SPA levels in relation to 751 U/L after the cut-off value of SPA level was determined as 751 U/L. HAI scores and fibrosis stage was significantly higher in patients with a SPA level of >751 U/L (p=0.02, p=0.004) (Table 5).

Table 4: Comparison between asymptomatic HBV carriers and HBeAg (-) CHB patients.

| Results | Asymptomatic HBV carriers (n=65) | HBeAg-negative CHB patients (n=45) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBV DNA (×10³ IU/ml) | 0,561.66 ± 554.48 | 15758 ± 53677.72 | 0.001 |

| Prolidase, (U/L) | 732.99± 124.70 | 824.32 ± 115.06 | 0.001 |

| Serum CK18 (U/L) | 238.41 ± 107.91 | 225.70 ± 89.93 | ns. |

| Hepatosteatosis Grading (US) (N/G1/G2/G3) | 49/10/6/0 | 39/6/0/0 | ns. |

| HAI (mild / medium / severe) | 52 / 13 / 0 | 20 / 23 / 2 | 0.001 |

ns.: Not significant, CK18: Cytokeratin-18; G: Grade; HAI: Histologic Activity Index; US: Ultrasonography

Table 5: Clinical and laboratory findings of HBeAg (-) CHB patients according to serum prolidase levels.

| Serum Prolidase activity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Results | <751 U/L (n=12) | >751 U/L (n=33) | p value |

| HBV DNA (×10³ IU/ml) | 16416.16 ± 4848.43 | 19891.52 ± 5585.07 | AD |

| Hepatosteatosis Grading (US) (N/G1/G2/G3) | 10/2/0/0 | 29/4/0/0 | AD |

| HAI (mild/medium/severe) | 04-07-2001 | 4/18/11 | 0.025 |

| Fibrosis, (mild/moderate/severe) | 05-06-2001 | 02-12-2009 | 0.004 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | AD |

| Ground glass (+/-) | 3 (25) | 8 (24) | AD |

| Hydropic degeneration (+/-) | 1 (8) | 3 (9) | AD |

ns.: Not significant; AFP: Alpha-Fetoprotein; FBG: Fasting Blood Glucose; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase, ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase, AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; GGT: Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase; HBV: Hepatitis B Virus, PT: Prothrombin Time, VKI: Body Mass Index; CK18: Cytokeratin-18; G: Grade; HAI: Histologic Activity Index, US: Ultrasonography

When SPA level reached 751 U/L, sensitivity was found to be 72%, specificity to be 63%, positive likelihood ratio to be 1.97 and negative likelihood ratio to be 0.43 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The area that remains under the curve when the diagnostic efficiency of serum prolidase value in asymptomatic HBV carriers and HBeAg negative CHB patients’ group is tested with the ROC analysis= (0.707 95% CI (0.612-0.790).

Discussion

The majority of patients with CHB are asymptomatic and the disease usually follows a silent chronic course. Liver biopsy is considered the gold standard for the detection of viral hepatitis activity [13,14]. It is stated that the best approach for chronic HBV infection should be followed up with ALT levels and HBV DNA measurements at three-month intervals in a one-year period and the asymptomatic carriers should be separated by chronic hepatitis [15,16]. However, it is emphasized that significant histopathological progression may not be predicted in about 10% of patients considered as asymptomatic carriers without liver biopsy [15,17]. A recent study has demonstrated that active disease and even cirrhosis may be observed in patients although their ALT and HBV-DNA levels are normal [18].

The current problem related to asymptomatic HBV carriers is how they can be identified successfully and followed up. Chu et al. [19] followed up 1965 asymptomatic HBV carrier patients for an average of 11.5 years and determined that reactivation had developed in 314 (15%). Cirrhosis developed in subsequent years in 47 of these patients and without reactivation in 10 of 1651 patients who remained as carriers. In a study performed by Yu et al. [20], 1506 asymptomatic HBV carrier patients were followed up for an average of 7.1 years and cirrhosis was determined in 89 cases and HCC in 16 cases. Ter Borg et al. [21] performed liver biopsies in 174 asymptomatic carrier patients in Holland and determined cirrhosis in 10% of those patients. Al-Mahtab et al. [22] in their study recently performed liver biopsies on 141 patients who were followed up for being asymptomatic carriers and determined severe hepatic fibrosis (fibrosis score >3) in 12%. In their study including 95 asymptomatic carriers, Ikeda et al. [23] determined ≥ 2/6 fibrosis in 35% patients, ≥ 3/6 fibrosis in 12% and cirrhosis in 6%. In our study, the ratio of moderate-to-severe fibrosis (≥ 2/6) in asymptomatic HBV carriers was determined to be 15% and HAI (≥ 4/18) to be 20%. These results are in accordance with the literature and prompted us to conclude that the disease in asymptomatic HBV carriers is not dormant or harmless and either a non-invasive method determining fibrosis or histopathological examinations should be performed in carriers with a certain disease age.

Apoptosis has long been recognized as an important feature in chronic liver diseases. CK-18 is an intermediate filament protein expressed in hepatocytes that is proteolytically dissolved during the liver injury. The cytokeratin 18 epitope M30 has been identified as a sensitive indicator of cell death. During apoptosis, activated caspases 3,6,7 and 9 can dissolve CK-18 at specific peptide recognition sites. As a result of the caspase activity, CK-18 is cut at 387th and 396th positions and frees the M30 fragment [24,25]. Recently, it has been shown that the increased levels of M30 fragment of CK-18 could be used as an indicator for the inflammation activity and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C and Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) [26].

In the study by Jazwinksi et al. [27], it was shown that the serum concentration of CK-18 reflected not only the development of fibrosis but also the disease activity. In this study, it was reported that the CK-18 serum levels indicated active liver inflammation even in patients with normal ALT levels when they were >253U/L.

However, Abdel et al. [28] showed that the serum levels of CK-18 were higher in patients with liver diseases than in the healthy control group (p<0.01) and the highest serum CK-18 levels were seen in patients with severe liver fibrosis. In another study by Cavalgia et al. [29], it was shown that there is a significant relationship between CK18 and the severity of liver fibrosis (r=0.329; p=0.0126). In the present study, however, the serum CK18 levels were found to be lower in the healthy control group than in asymptomatic HBV carriers and CHB patients. There was no difference between CHB patients and asymptomatic HBV carriers. A positive correlation was seen between CK18 and HAI and HBV DNA in asymptomatic HBV carriers. However, there was no correlation between ALT and the severity of fibrosis.

Prolidase is involved in breaking down iminodipeptides formed after collagen degradation. Several studies have shown that there is an association between SPA level and fibrotic activity. First, Myara et al. [6] determined high SPA in chronic liver disease patients and reported that SPA increases in parallel with the degree of fibrosis [7,8,30]. In our study, SPA level was significantly higher in CHB patients compared to asymptomatic carriers and was significantly higher in asymptomatic carriers compared to healthy volunteers.

SPA level was significantly higher in CHB patients with moderateto- severe fibrosis and asymptomatic carriers compared to patients with mild fibrosis. These results have helped us conclude that SPA, due to its effects on collagen degradation and direct association with fibrotic tissue development, may be valuable in the long-term follow-up process of chronic liver patients and in monitoring their response to treatment.

In three separate studies supporting this opinion, it has been shown that SPA is a useful marker in evaluating liver fibrosis and SPA level increases in parallel with the increase in the stage of fibrosis [31,32]. The difference between our study and previously performed studies is the performance of liver biopsy of asymptomatic carriers and their comparison with the biopsy results of CHB patients and healthy volunteers. Kayadibi et al. [5] investigated the diagnostic value of SPA by determining the histological changes in the liver in patients with NASH and their results are comparable with those reported by us. In their study, the SPA level of patients with steatohepatitis was significantly increased compared to that in the control group and the group with simple steatosis and it correlated with the stage of fibrosis and the enzyme activity score. Another study investigating the association between SPA and ultrasonic staging in patients with NASH, it was determined that as the grade of steatosis on ultrasonography increases, SPA also increases and this condition has been linked to the possibly increased fibrotic activity [9].

All these studies have demonstrated that determining SPA level may be an important test for diagnosing fibrosis. However, none of the non-invasive tests is a safe indicator as histological evaluation. Today, liver biopsy is still the gold-standard method for the evaluation of necroinflammation and liver fibrosis. However, in cases where a biopsy cannot be performed and where repeated biopsy is required, the use of these non-invasive tests may be useful.

In our study, SPA level was significantly higher in patients with HBeAg-negative CHB patients compared to asymptomatic HBV carriers. The diagnostic efficiency of SPA in differentiating HBeAgnegative CHB patients from asymptomatic HBV carriers was also examined in our study. Accordingly, the diagnostic efficiency of SPA was found to be strong, and 45 patients with HBeAg-negative active CHB were divided into two groups according to their low and high SPA value of 751 U/L after determining the cut-off value of SPA as 751 U/L. HAI and the stage of fibrosis were significantly higher in patients with a SPA level of >751 U/L.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the SPA level is associated with fibrosis in CHB patients. It may be a useful non-invasive test in discriminating asymptomatic HBV carriers and HBeAg- negative CHB patients. Serum CK-18 levels were found to be related only to the level of liver necroinflammation. Prospective studies with large populations requiring long-term follow up are required to determine whether SPA, which has been determined to exhibit high sensitivity for being an indicator of fibrosis, can be a serum marker.

It was found that the SPA is correlated with fibrosis and necroinflammation in CHB patients, and serum CK18 levels were predominately correlated with liver necroinflammation. Based on this study, it is considered the use of SPA along with ALT and HBV DNA levels in distinguishing asymptomatic HBV carriers from CHB patients can provide clinical benefit. There is a need for more comprehensive and prospective studies on this subject.

Declarations

Funding

This project received no funding.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors

Disclosure

We have no relevant financial or nonfinancial relationships to disclose.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- Hadziyannis SJ, Papatheodoridis GV. Hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B: natural history and treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26(2):130–141.

- Chu CM, Hung SJ, Lin J, Tai DI, Liaw YF. Natural history of hepatitis B e antigen to antibody seroconversion in patients with normal serum aminotransferase levels. Am J Med. 2004;116(12):829–834.

- Goyal SK, Jain AK, Dixit VK, Shukla SK, Kumar M, Ghosh J, et al. HBsAg level as predictor of liver fibrosis in HBeAg positive patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2015;5(3):213–220.

- McMahon BJ. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2009;49(S5):S45-S55.

- Kayadibi H, Gultepe M, Yasar B, Ince AT, Ozcan O, Ipcioglu OM, et al. Diagnostic value of serum prolidase enzyme activity to predict the liver histological lesions in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a surrogate marker to distinguish steatohepatitis from simple steatosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(8):1764–1771.

- Myara I, Myara A, Mangeot M, Fabre M, Charpentier C, Lemonnier A. Plasma prolidase activity: a possible index of collagen catabolism in chronic liver disease. Clin Chem. 1984;30(2):211–215.

- Horoz M, Aslan M, Bolukbas FF, Bolukbas C, Nazligul Y, Celik H, et al. Serum prolidase enzyme activity and its relation to histopathological findings in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2010;24(3):207–211.

- Stanfliet JC, Locketz M, Berman P, Pillay TS. Evaluation of the utility of serum prolidase as a marker for liver fibrosis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2015;29(3):208–213.

- Arora A, Sharma P. Non-invasive diagnosis of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012;2(2):145–155.

- Kaleli S, Karabay O, Guclu E, Karabay M. Serum prolidase activity as an indicator of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B infection. Biomed Res. 2017;28(17):7604–7607.

- Feldstein AE, Wieckowska A, Lopez AR, Liu YC, Zein NN, McCullough AJ. Cytokeratin-18 fragment levels as noninvasive biomarkers for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicenter validation study. Hepatology. 2009;50(4):1072–1078.

- Ueno T, Toi M, Biven K, Bando H, Ogawa T, Linder S. Measurement of an apoptotic product in the sera of breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(6):769–774.

- Gonzalez-Quintela A, Mallo N, Mella C, Campos J, Perez LF, Lopez-Rodriguez R, et al. Serum levels of cytokeratin-18 (tissue polypeptide-specific antigen) in liver diseases. Liver Int. 2006;26(10):1217–1224.

- Mani H, E Kleiner D. Liver biopsy findings in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49(S5):S61-S71.

- Terrault NA, Lok ASF, Mcmahon BJ, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67(4):1560–1599.

- Lampertico P, Agarwal K, Berg T, Buti M, Janssen HLA, Papatheodoridis G, et al. EASL 2017 Clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67(2):370-398.

- Puoti C. HBsAg carriers with normal ALT levels: Healthy carriers or true patients? Brit J Med Practitioners. 2013;6(1):0–1.

- Kim HC, Nam CM, Jee SH, Han KH, Oh DK, Suh I. Normal serum aminotransferase concentration and risk of mortality from liver diseases: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2004;328(7446):983.

- Chu CM, Liaw YF. Incidence and risk factors of progression to cirrhosis in inactive carriers of hepatitis B virus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(7):1693–1699.

- Yu MW, Hsu FC, Sheen IS, Chu CM, Lin DY, Chen CJ, et al. Prospective study of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in asymptomatic chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(11):1039–1047.

- Ter Borg F, Ten Kate FJ, Cuypers HT, Leentvaar-Kuijpers A, Oosting J, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, et al. A survey of liver pathology in needle biopsies from HBsAg and anti-HBe positive individuals. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53(7):541–548.

- Abdulsalam SI, Abdulatif A, Joyal J, Wisam G, Ajayeb A. Hepatitis E in Qatar imported by expatriate workers from Nepal: Epidemiological characteristics and clinical manifestations. J Med Virol. 2009;81(6):1047–1051.

- Ikeda K, Arase Y, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Someya T, Hosaka T, et al. Long-term outcome of HBV carriers with negative HBe antigen and normal aminotransferase. Am J Med. 2006;119(11):977–985.

- Luft T, Conzelmann M, Benner A, Rieger M, Hess M, Strohhaecker U, et al. Serum cytokeratin-18 fragments as quantitative markers of epithelial apoptosis in liver and intestinal graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2007;110(13):4535–4542.

- Li C, Liu S, Lu L, Dong Q, Xuan S, Xin Y. Association between serum cytokeratin-18 neoepitope M30 (CK-18 M30) levels and chronic hepatitis B: A meta-analysis. Hepat Mon. 2018;18(4).

- Neuman MG, Cohen LB, Nanau RM. Biomarkers in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(11):607–618.

- Jazwinski AB, Thompson AJ, Clark PJ, Naggie S, Tillmann HL, Patel K. Elevated serum CK18 levels in chronic hepatitis C patients are associated with advanced fibrosis but not steatosis. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(4):278–282.

- Haleem HA, Zayed N, Hafez HA, Fouad A, Akl M, Hassan M, et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic value of serum and tissue apoptotic cytokeratin-18 in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2013;14(2):68–72.

- Caviglia GP, Ciancio A, Rosso C, Lorena Abate M, Olivero A, Pellicano R, et al. Non-invasive methods for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis: Transient elastography, hyaluronic acid, 13C-aminopyrine breath test and cytokeratin 18 fragment. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13(1):91–97.

- Duygu F, Aksoy N, Cicek AC, Butun I, Unlu S. Does prolidase indicate worsening of hepatitis B infection? J Clin Lab Anal. 2013;27(5):398–401.

- Brosset B, Myara I, Fabre M, Lemonnier A. Plasma prolidase and prolinase activity in alcoholic liver disease. Clin Chim Acta. 1988;175(3):291–295

- Gultepe M, Ozcan A, Altin M, Ozturk G, Demirci M. Evaluation of the response of hepatic fibrosis to colchicine treatment by estimating serum prolidase activity and procollagen III amino terminal propeptide levels. Turk J Med Sci. 1994;20:99–104.

Citation: Yılmaz N, Balkan A, Koruk M (2019) Importance of Prolidase Enzyme Activity and Serum Cytokeratin 18 Levels for Differential Diagnosis between Asymptomatic Hepatitis B Carriers and HBeAg Negative Chronic Hepatitis B Patients. J Liver 8:237.

Copyright: © 2019 Yılmaz N, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.