Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Academic Keys

- ResearchBible

- China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI)

- Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI)

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- CABI full text

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research - (2024) Volume 12, Issue 1

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children's Mental Health in Taiwan: 2021-2022, Two-Year Follow-up Study

Wei-Hsien Chien1*, Hsin-Fang Chang2, Kai-Hsun Wang3,4, Yi-Nuo Shih1, Yi-Hsien Tai3, Ming-chih Chen3 and Ben-Chang Shia3,4*2Department of MS Program in Transdisciplinary Long-Term Care, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, Taiwan

3Graduate Institute of Business Administration, College of Management, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, Taiwan

4Department of Artificial Intelligence Development Center, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, Taiwan

Received: 31-Jan-2024, Manuscript No. JTD-24-24733; Editor assigned: 05-Feb-2024, Pre QC No. JTD-24-24733 (PQ); Reviewed: 20-Feb-2024, QC No. JTD-24-24733; Revised: 28-Feb-2024, Manuscript No. JTD-24-24733 (R); Published: 07-Mar-2024, DOI: 10.35241/2329-891X.24.12.422

Abstract

Background: According to the most comprehensive mental health report in the past two decades by the World Health Organization, nearly one billion people experienced mental health issues prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Following its outbreak in 2021, the rates of depression and anxiety increased by 25%, which highlights its impact on mental health at the global scale. This study aims to elucidate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s mental health and to raise awareness among various stakeholders, including educators and governments.

Methods: To analyze and evaluate the indicators of mental health in children, we used a structured questionnaire that was previously designed with good reliability and validity. We focused on assessing six major categories related to children’s mental health in 2021 and 2022. We collected 1,000 valid responses from parents and their children for in-depth analysis (men: 538; women: 462).

Results: The average total indices of children’s mental health were 66.50 and 63.83 in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The results of the six indices for both years were as follows: “Personal Life”: 68 and 66; “Family Life”: 70 and 70; “Peer Relationship”: 77 and 73; “School Life”: 68 and 68; “Online Social Interaction”: 60 and 55; and “Epidemic Life”: 56 and 51, respectively. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the top three activities of children aside from attending online classes were watching TV (66.0%), browsing the Internet (62.0%), and playing video games (50.7%).

Conclusion: Children reported challenges with online exposure and academic pressure. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected their mental health, which impacted learning, socializing, and family dynamics. Specifically, family dynamics and environment emerged as significant influencing factors on the overall well-being of the children during these times. Consequently, collaborative effort among schools, communities, and governments is essential for improving or maintaining the mental health of children.

Keywords

COVID-19; Children mental health; Questionnaire

Abbreviations

WHO: World Health Organization; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; PTSD: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; CDI-S: Children’s Depression Inventory-Short Form

Introduction

According to the scientific briefing of World Health Organization (WHO) in 2022, the global prevalence of anxiety and depression has significantly increased by 25% during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic [1].

The impact of the pandemic on children’s mental health has received widespread attention and research. For example, a systematic review found that the mental health of adolescents and young people had deteriorated since the beginning of the pandemic with increases in the cases of depression, anxiety, and psychological stress [2]. Other findings included worsened negative emotions, increased sense of loneliness, and compromised mental well-being. Comparing data from the pandemic to the prepandemic periods indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic has, indeed, exerted a negative impact on the mental health of children and adolescents [2].

A systematic review and meta-analysis involving approximately 50,000 children and adolescents from China and Turkey, which was based on 23 studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019-2020, revealed that 29% and 26% of the global child and adolescent populations were diagnosed with depression and anxiety, respectively [3]. This finding indicated that they faced emotional and psychological pressure and may have experienced feelings of sadness, worry, and restlessness. Among them, 44% reported sleep disorders, which may include difficulty in falling asleep, frequent awakening at night, and decreased sleep quality. Sleep disturbance could be related to stress and anxiety. Furthermore, 48% reported symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), including memories of traumatic events, nightmares, anxiety, and avoidance of stimuli. The pandemic may have triggered stress and psychological trauma, which have led to the emergence of these symptoms. This result indicates that children and adolescents experienced serious mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic [3].

Research has assessed and described the changes in mental health issues among children presenting at large tertiary pediatric emergency departments in the United States before and after the pandemic. The study found that despite an overall decrease of 39% in emergency department visits, a significant increase occurred in the proportion of children seeking care for mental health problems during the pandemic (from 4.88% to 5.22%) [4]. A recent study in China investigated the behavioral and emotional disturbances experienced by children and adolescents due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study found that clinginess, distractibility, irritability, and anxiety related to the fear of family members contracting the virus were the most common behavioral problems among children [5]. Furthermore, children and adolescents may exhibit various symptoms of psychological distress, which may include anxiety, depression, feelings of loneliness, and decline in academic performance [6].

During infectious disease pandemics, children are particularly susceptible to develop behavioral problems such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), conduct issues, and general psychological distress due to lifestyle changes and social psychological stress caused by home confinement [7]. Younger children aged approximately 3 to 6 years may lose their previous behavioral autonomy, experience psychological panic, and become increasingly reliant on primary caregivers [5]. A few children may exhibit regressive behaviors such as increased demand for pacifiers, refusal to dress or eat independently, bedwetting, increased clinginess, and sleep issues. Changes in sleep patterns may include difficulty in falling asleep, multiple nighttime awakening, nightmare, and crying spell [7]. Older children (>7 years old) may experience difficulty with attention and increased anxiety. The requirements to maintain social distancing and restrict social activities during the pandemic prevent them from freely engaging in social interaction with peers and from enjoying its subsequent fulfillment. Consequently, they may feel lonely and helpless [5,8-11]. From the perspective of social isolation, scholars also assessed the impact of the pandemic on children’s mental health. Research found that loneliness increases the risk of developing depression and anxiety disorders, and the longer that children experience feelings of loneliness, the more profound the impact on their mental health [12]. Children who lack companionship in their daily lives, such as those with limited opportunities to interact with peers at school or engage in social activities, are more susceptible to feelings of loneliness [13,14]. Children who are suspected or diagnosed with COVID-19 and are placed in isolation may experience mental health disorders such as anxiety, acute stress, and adjustment difficulty. Additionally, other factors, such as separation from parents, stigmatization, fear of the unknown disease, and social isolation, can exert negative psychological effects on children [15]. Research demonstrated that the negative psychological impact of isolation can still be detected even months or years later. Children who were separated from their caregivers exhibited a fourfold increase in scores on the Traumatic Stress Symptom Scale, on average, compared with children who were not separated [16]. Another study indicated that 30% of children who were separated from their caregivers met the criteria for PTSD [17].

However, when children are forced to stay at home due to the pandemic, they lack outdoor activities and interaction with peers [18]. They also tend to spend excessive time on smartphones, computers, and TV screens, which leads to irregular sleep patterns, disrupted dietary routines, weight gain, and a decline in cardiovascular fitness, which, in turn, affect mental health [19,20].

According to a study on the impact of COVID-19 on stress levels among children and adolescents in South Korea, the greatest stress factor identified was the restriction of outdoor activities. The inability to interact with friends or enjoy outdoor activities as they previously did cause stress and emotional distress. Additionally, the increased burden on parents to take care of the family limited their ability to provide effective support and companionship, which led adolescents to increasingly rely on social media to fulfill their social and entertainment needs. This scenario increased their sense of social isolation. Finally, this environment of social isolation may contribute to the emergence of symptoms similar to ADHD in adolescents such as the lack of concentration, anxiety, and emotional instability [21].

Furthermore, research pointed to a close relationship between parents’ emotional state, stress levels, and conditions of psychological well-being and children’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [8]. Parents may face difficulties at work, reduced income, and increased caregiving burden during the pandemic, which can increase the risk of domestic violence and child abuse [22]. In turn, children become exposed to witnessing or experiencing family violence, emotional discord, and physical and/ or sexual abuse, which leads to several mental health problems in children and adolescents [17,23].

A number of studies have found the association of parental depression, unemployment, and the previous abusive behavior of parents with increased abuse rates in children, particularly among children aged 4 to 10 years [22]. Moreover, research on parenting styles has indicated that when families exhibit more support and a sense of control, the likelihood of parental abuse toward children is lower [24]. Isolation, loneliness, lack of physical activity, and family stress may contribute to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents [25].

Previous studies have documented the negative effects of the excessive use of smartphones and the internet on the mental health and behaviors of children and adolescents, such as poor academic performance, reduced real-life social interaction, neglect of personal life, interpersonal difficulty, and increased risk of affective disorders [26]. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Internet and 3C’s (computer, communication, and consumer electronics) device usage have become essential tools for communication with the outside world. Although a number of parents reported the successful use of media entertainment to relax the emotion of their children during the initial weeks of the pandemic [5], a large-scale study that focused on children and adolescents found that excessive use and addiction to smartphones and the Internet may increase the risk of depression [27].

During periods of social isolation, children and adolescents are exposed to excessive media coverage of COVID-19. Electronic and social media constantly provide updates on the status of the national pandemic and advise people to maintain social distancing. It also generates sensationalism and spreads misinformation. Research has demonstrated that excessive television exposure following the 9/11 attacks led to increased rates of PTSD and other mental health disorders. Thus, concerns emerge that children may experience similar conditions due to the excessive use of electronic and social media. Additionally, the excessive use of social media renders children vulnerable to online predators, cyberbullying, and harmful content [14]. A survey on high school students with Internet addiction have illustrated that anxiety disorders are the most common diagnosis [28]. Furthermore, individuals who use electronic media prior to sleeping are more likely to experience sleep disorders or adverse effects on sleep quality, which were significantly associated with depression [29].

During the pandemic, engaging in regular physical exercise may efficiently reduce behavioral problems and improve mental health in children. Therefore, these children exhibit less symptoms of hyperactivity and inattention and engage more in prosocial behavior [30]. Conversely, the lack of physical exercise is associated with high levels of depression and anxiety. Therefore, researchers recommend that physical activity may serve as a protective factor by helping alleviate negative emotions and promote mental health in children during the pandemic [31].

The increased stress experienced by children due to COVID-19 can also lead to a decrease in personal well-being. Research highlighted that the perception of children and adolescents of the risk of COVID-19 can directly affect mental health. Two studies examined such negative effects on children and adolescents living in areas with high incidence rates of COVID-19. The first reported on children in Hubei province, China, and found that those who were pessimistic about the epidemic displayed significantly higher scores in the Children’s Depression Inventory-Short Form (CDI-S) with an increased risk of depressive symptoms compared with those with optimism [10]. The second found that elementary school students who expressed high levels of concern about threats to their life and health exhibited more physical symptoms of anxiety. This finding indicates that worries and perceived threats related to the pandemic can exert a negative impact on the mental health of children and adolescents [24].

Evidence has shown that exposure to COVID-related information can impact the mental health of children. A large-scale study conducted after one month of quarantine revealed that excessive exposure to pandemic-related media coverage may increase anxiety and PTSD symptoms [13]. However, the study also found that children seemingly benefited from discussions of COVID-19 with parents. Those whose parents did not engage in such discussions reported high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. Furthermore, the study focusing on adolescents demonstrated that those who had discussions with their parents about the pandemic exhibited a deep understanding of COVID-19, displayed optimism, adopted more safety measures, and experienced lower levels of depression and anxiety [13].

The objective of the current study is to enhance the understanding of the impact of the pandemic on the mental well-being of children and to raise awareness among various stakeholders, including educators and governments.

Materials and Methods

This study aims to analyze and evaluate the indicators of children’s mental health using a quantitative approach. Toward this end, we designed a structured questionnaire that focuses on assessing various domains related to children’s mental health, including six major categories (Table 1).

| Please select the option that best describes your situation for the following questions | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Life | I am very happy and joyful when I smile. | |||||||

| I feel bored. | ||||||||

| I feel lonely. | ||||||||

| I feel scared. | ||||||||

| I think highly of myself. | ||||||||

| I like myself. | ||||||||

| Family Life | The main person who takes care of me is □Mom and Dad □Grandparents or grandparents □ Other person | |||||||

| I get along well with my parents or the main person who takes care of me. | ||||||||

| I feel comfortable at home. | ||||||||

| There are people at home who argue a lot. | ||||||||

| Parents forbid me from doing certain things | ||||||||

| Peer Relationships | I play with my friends. | |||||||

| Classmates and friends all like me. | ||||||||

| I get along well with my friends | ||||||||

| I am teased or bullied at school. | ||||||||

| School Life | I complete my schoolwork and it’s not difficult. | |||||||

| Classes are interesting. | ||||||||

| Teachers chat with us like friends or help me | ||||||||

| I feel ignored by teachers. | ||||||||

| I worry about my future. | ||||||||

| Worried about poor grades. | ||||||||

| Online Social Interaction | Spending more time online than expected | |||||||

| Parents complain about spending too much time online | ||||||||

| I can make new friends online. | ||||||||

| I feel frustrated if I can’t go online, but I feel better once I’m online. | ||||||||

| I prefer spending more time online rather than engaging in outdoor activities | ||||||||

| COVID-19 Prevention Lifestyle | I worry about myself or my family getting COVID-19 | |||||||

| I worry about falling behind in my schoolwork and feel academic pressure | ||||||||

| I worry about myself or my family needing to be separated or isolated. | ||||||||

| The pandemic has affected my daily routines and lifestyle. | ||||||||

| Apart from studying at home, what other activities do you engage in? Please select three options by circling them. | ||||||||

| Watching TV | Listening to music | Browsing the internet | Reviewing homework | |||||

| Playing video games | Talking on the phone | Reading books | Other | |||||

Note: Total score of each item is 100. (Never=1, Rarely=25, Sometimes=50, Often=75, Always = 100)

Table 1: Questionnaire of children’s mental health items.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire of children’s mental health combined Likert scales and open-ended questions to obtain comprehensive data from the quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Prior to the study, the researchers conducted a comprehensive analysis of the reliability and validity of the questionnaire [32,33]. Reliability analysis primarily assessed the internal consistency of the questionnaire using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, while validity analysis included expert review and a pilot study to ensure an accurate measurement of the intended constructs. The questionnaire demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency with a calculated Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.7191, which indicates reliability in assessing the intended construct(s).

The questionnaire is divided into six major categories, namely, personal life, family life, peer relationships, school life, online social interaction and pandemic life. Items were rated using a five-point Likert-type scale (1=Never, 25=Rarely, 50=Sometimes, 75=Often, 100=Always. Total score=100, Table 1).

The survey was conducted online. Regarding sample selection, the target population consisted of children aged 9 to 12 years (male: n=538 (53.8%); female: n=462 (46.2%)) with a total of 1,000 valid responses. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed using SPSS and R.

In terms of ethical considerations, written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of the children, and a strict protocol for data anonymization and confidentiality was followed.

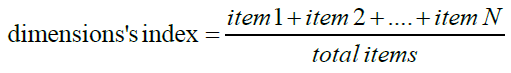

Calculation of children’s mental health index

The index was calculated by averaging the scores of the items within each of the six dimensions. The index of each dimension ranges from 0 to 100. As the questionnaire includes positively and negatively worded items, the scores for positively worded items increase with higher frequency, whereas the scores for negatively worded items decrease with higher frequency. In the end, regardless of whether the item is positively or negatively worded, a higher index indicates a higher level of health. The calculation formula is as follows:

Results

Scores for each dimension

Table 2, presents the results of the children’s mental health index for 2021 and 2022. The results of various indices of children’s mental health for both years were as follows: Personal Life Index: 68 and 66; Family Life Index: 70 and 70; Peer Relationship Index: 77 and 73; School Life Index: 68 and 68; Online Social Interaction Index: 60 and 55; and Epidemic Life Index: 56 and 51, respectively. The average total indices for children’s mental health for 2021 and 2022 were 66.50 and 63.83, respectively (Table 2).

| 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Life Index | 68 | 66 |

| Laughing and feeling happy | 77 | 75 |

| Feeling bored | 57 | 53 |

| Feeling lonely | 63 | 65 |

| Feeling afraid | 64 | 65 |

| Feeling great about myself | 68 | 65 |

| Liking myself | 74 | 70 |

| Family Life Index | 70 | 70 |

| Getting along well with parents | 82 | 84 |

| Feeling comfortable and relaxed at home | 83 | 85 |

| Experiencing frequent arguments at home | 70 | 68 |

| Parents forbid me from doing certain things | 46 | 44 |

| Peer Relationship Index | 77 | 73 |

| Playing with friends | 75 | 67 |

| Being liked by classmates and friends | 77 | 73 |

| Having good relationships with friends | 77 | 75 |

| Experiencing teasing, bullying, or domination at school | 78 | 78 |

| School Life Index | 68 | 68 |

| Completing schoolwork and finding it easy | 74 | 75 |

| Finding classes interesting | 70 | 67 |

| Teachers being helpful like friends | 70 | 68 |

| Feeling ignored by teachers | 69 | 70 |

| Worries about the future | 66 | 67 |

| Worried about poor grades | 58 | 59 |

| Online Social Interaction Index | 60 | 55 |

| Spending more time online than expected | 52 | 45 |

| Parents complaining about excessive internet use | 49 | 41 |

| Making new friends online | 71 | 70 |

| Feeling frustrated without internet access | 66 | 61 |

| Preferring online activities over outdoor activities | 62 | 59 |

| Epidemic Life Index | 56 | 51 |

| Worries about contracting COVID-19 for myself/family | 55 | 48 |

| Worries about falling behind in schoolwork and feeling pressure | 56 | 55 |

| Worries about being quarantined for myself/family | 59 | 54 |

| Disruption of daily routines due to the pandemic | 54 | 48 |

Table 2: Children’s mental health index.

The Personal Life Index displayed a slight decrease from 68 to 66 points in 2022, which indicates a possible reduction in the happiness and self-evaluation of the children of their daily life. Notably, the item of “Feeling lonely” improved in 2022, but the study observed a decline in other items such as “Laughing and feeling happy,” “Feeling bored,” “Feeling great about myself,” and “Liking myself.” Furthermore, the Personal Life Index of the children can be assessed based on factors such as whether or not they feel happy, like themselves, or feel lonely and scared. The children generally displayed positive overall health in their personal lives, except for occasional boredom. They reported very positive experiences in terms of getting along with parents and feeling good at home, which indicates high levels of health in these areas.

“The Family Life Index remained stable across the two years, which consistently scored 70 points. This result indicates a relative stability in the experiences and feelings of the children within the family environment, including interactions with parents, the family atmosphere, and family conflicts. However, the item “Parents forbid me from doing certain things” obtained only 46 and 44 points for 2021 and 2022 (Table 2), respectively, which suggests that parents employ timely intervention and management approaches with their children.

The Peer Relationships Index exhibited a significant decline from 77 to 73 points in 2022, which indicates that the children faced more challenges in interacting with friends, gaining acceptance from peers, and navigating social experiences at school during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the children reported positive relationships with peers and enjoyed interacting with them. They experienced very few instances of being teased or bullied in school, which pointed to overall positive peer relationships.

The school life index remained the same at 68 points for two consecutive years. This consistent score suggests that the experiences of children with academic completion, classroom engagement, and interaction with teachers did not undergo significant changes. In terms of interaction with teachers and class attendance, the children reported positive experiences, although the item “Worried about poor grades” obtained the lowest score (Table 2), which indicates that academic performance is a concern for children.

The online social index decreased by 5 points (from 60 to 55) in 2022. This decline may be related to changes in the internet use of the children, parental attitudes toward Internet use, and shift in online social activities. The study identified the items “Spending more time online than expected” and “Parents complain about spending too much time online” as more significant issues related to the Internet use and social interaction of the children.

The Pandemic Life Index also exhibited a decrease from 56 to 51 points in 2022. This decline may be attributed to the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily lives of the children, including health concerns, academic pressures, and restrictions on social activities.

Comparing the changes in the Children’s Mental Health Index between 2021 and 2022, Table 3, demonstrates that the overall index decreased from 66.50 to 63.83 points. Except for the family life and school life indices, which remained the same, all other dimensions experienced a decline. Specifically, the “Online social” and “Epidemic life” indices displayed the most significant decreases of 5 points followed by a four-point decline in “Peer relationships” and a two-point decline in “Personal life.” In summary, children exhibited regression in mental health performance in 2022 compared with that in 2021 (Table 3).

| Index aspect | 2021 | 2022 | Increase/decrease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal life index | 68 | 66 | -2 |

| Family life index | 70 | 70 | 0 |

| Peer relationship index | 77 | 73 | -4 |

| School life index | 68 | 68 | 0 |

| Online social interaction index | 60 | 55 | -5 |

| Epidemic life index | 56 | 51 | -5 |

| Children’s mental health index | 66.5 | 63.83 | -2.67 |

Table 3: Children’s mental health index summary table.

The pandemic significantly impacted the years 2021 and 2022, and none of the mental health indices increased. In fact, four indices decreased, which indicates that the persistent state of the pandemic has exerted an impact on the mental health of children, including concerns about health, academic stress, and restriction on social activities.

The Epidemic life index displayed a lower score, which indicates a less healthy state and reflects the pressure faced by the children in their academic and daily lives due to the prolonged pandemic situation. The children reported no major issues with hardware and software for online classes. However, they expressed concern about the lack of interaction with teachers and classmates, as well as lagging behind in progress, which made them feel that online learning was less effective.

In addition to attending online classes at home, Table 4, depicts that the most common activities reported by the respondents were watching TV (66.0%), browsing the Internet (62.0%), playing video games (50.7%), reviewing homework (35.6%), and reading books (34.1%) (Table 4).

| Content | Number of people | (%) | Content | Number of people | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Watching TV | 660 | 66 | Playing badminton | 1 | 0.1 |

| Listening to music | 263 | 26.3 | Eating and drinking | 2 | 0.2 |

| Browsing the Internet | 620 | 62 | Having a meal | 1 | 0.1 |

| Reviewing homework | 356 | 35.6 | Doing chores | 2 | 0.2 |

| Playing video games | 507 | 50.7 | Playing with younger sister | 2 | 0.2 |

| Making phone calls and chatting | 96 | 9.6 | Playing | 2 | 0.2 |

| Reading books | 341 | 34.1 | Playing on a mobile phone | 1 | 0.1 |

| Taking violin lessons | 2 | 0.2 | Playing with toys | 6 | 0.6 |

| Doing crafts | 2 | 0.2 | Playing board games | 1 | 0.1 |

| Playing mobile games | 1 | 0.1 | Playing puzzle games | 1 | 0.1 |

| Watching TV | 2 | 0.2 | Playing video games | 2 | 0.2 |

| Watching TV or online learning | 2 | 0.2 | Playing with modelling clay | 2 | 0.2 |

| Engaging in paper crafts | 2 | 0.2 | Playing with LEGO | 1 | 0.1 |

| Spending time with younger siblings | 2 | 0.2 | Playing LEGO and electronic keyboard | 2 | 0.2 |

| Exercise | 2 | 0.2 | Watching YouTube | 2 | 0.2 |

| Practicing talents | 2 | 0.2 | Drawing | 4 | 0.4 |

| Practicing playing the flute | 2 | 0.2 | Drawing and doing crafts | 2 | 0.2 |

Table 4: Activities outside of home-based learning.

Discussion

First, the COVID-19 pandemic has exerted a significant impact on children’s mental health, particularly in terms of learning and socialization. For instance, Winfield et al. (2023) found that the pandemic has led to increased family stress and reduced peer interaction due to home-based learning, which may contribute to the emergence of mental health issues and symptoms [34]. This finding aligns with the current results in which the children reported issues related to Internet use and socialization (e.g., “Spending more time online than expected” and “Parents complaining about excessive screen time”). These problems may reflect changes in the lifestyles of the children during the pandemic in which adaption which may require more time and support.

Second, academic pressure is another important factor that affects the mental health of children. Specifically, the children scored the lowest on the item “Worries about academic performance,” which indicates that academic achievement is a concern for them. This finding is consistent with those of Pudpong et al. (2022), who found increased academic stress among students during the pandemic, which may pose negative implications for mental health [35]. These results underscore the impact of academic pressure on children’s mental health and highlight the need for additional resources and strategies to help children cope with such pressure.

Lastly, family environment and parenting style also play a crucial role in children’s mental health. The children reported positive experiences with parental interaction and feeling at home but scored lower on the item “Parents forbid me from doing certain things,” which may reflect the influence of parenting styles. This result aligns with those of Park et al. (2022), who found that the pandemic has exerted a negative impact on family finances, which adds to the stress to fathers and may affect parenting stress levels and, subsequently, impact the mental health of children [36]. These results emphasize the importance of family environment and parental role to children’s mental health and highlight the need for more resources and strategies for supporting families and parents in coping with the challenges of the pandemic.

Additionally, the current findings demonstrated that the children scored low on the Pandemic Life Index, which reflects the impact of the pandemic on their daily lives. This finding is in agreement with those of Bourion-Bédès et al. (2022), who found a link between confirmed COVID-19 cases that require hospitalization or suspected cases in the family and moderate to severe anxiety [37]. These results underscore the impact of the pandemic on the daily lives of children and emphasize the need for further resources and strategies to help them cope with these stressors.

In summary, the findings emphasize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s mental health and provide potential explanations and strategies for addressing these issues. However, further research is required to gain an in-depth understanding of these impacts and to identify other effective methods for supporting children in coping with these pressures.

Conclusion

On the basis of the findings, we conclude that the COVID-19 pandemic has exerted a significant impact on the mental health of children. These impacts encompass various aspects such as learning, socialization, and family life. Particularly, the influences on academic stress, Internet usage, and social issues, as well as family dynamics and parental disciplinary practices, have been significant. In other words, they exert profound effects on children’s mental well-being.

First, providing additional resources and support, such as tutorials and psychological counseling services, to help children cope with academic stress is crucial. Second, children require assistance in developing healthy Internet usage and social habits such as setting reasonable screen time limits and encouraging face-toface interactions with peers. Lastly, families and parents must be supported by helping them establish effective disciplinary practices and providing necessary economic and psychological support.

Further research is needed to gain an enhanced understanding of the impact of the pandemic on children’s mental health and to identify further effective approaches to help them navigate these pressures. Additionally, collaboration among schools, communities, and governments is essential to collectively support the mental wellbeing of children. Only through such collaborative efforts can the challenges posed by the pandemic on children’s mental health be effectively addressed and their overall well-being is ensured.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Fu Jen Catholic University. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the participants after the procedures were fully explained. Each individual provided written informed consent prior to the subsequent online questionnaire survey. (Clinical Trial number: C110199).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declared no conflicts of interest and were responsible to their authorship in this article.

Competing interests

All authors declared no conflicts of interest and were responsible to their authorship in this article.

Funding

This research was supported by PCA Life Assurance Co., Ltd.

Authors' Contributions

Wei-Hsien, Chien initiated the idea, designed the study with Ben- Chang Shia and reviewed and edited the final draft of this article. Ben-Chang Shia designed the study and supervised in research execution. Hsin-Fang Chang and Yi-Nuo Shih reviewed the literatures. Kai-Hsun Wang and Yi-Hsien Tai reviewed the literature and performed analysis. Ming-Chih Chen reviewed the literature and edited this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the subjects, families, and research colleagues who participated in the study.

References

- World Health Organization. Scientific brief. Mar 2, 2022. World Health Organization: Geneva. WHO/2019-nCoV/Sci_Brief/Mental_health/2022.1. 2022; Mar 2: 1-11

- Kauhanen L, Wan Mohd, Yunus WM, Lempinen L, Peltonen K, Gyllenberg D, et al. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32(6):995-1013.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma L, Mazidi M, Li K, Li Y, Chen S, Kirwan R, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:78-89.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harel DS, Perera N, Ratnapalan S. 70 mental health in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: the experience of a North American tertiary care pediatric emergency department. Paediatr Child Health. 2022;27 Suppl 3:e33-34.

- Jiao WY, Wang LN, Liu J, Fang SF, Jiao FY, Pettoello-Mantovani M, et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr. 2020;221:264-6.e1.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wenter A, Schickl M, Sevecke K, Juen B, Exenberger S. Children's mental health during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic: burden, risk factors and posttraumatic growth–A mixed-methods parents’ perspective. Front Psychol. 2022;13:901205.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang G, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Zhang J, Jiang F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:945-947.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gassman-Pines A, Ananat EO, Fitz-Henley J. COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics. 2020;146:e2020007294.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick O, Carson A, Weisz JR. Using mixed methods to identify the primary mental health problems and needs of children, adolescents, and their caregivers during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2021;52:1082-1093.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, Zhu K, Liu Q, Zhang J, et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:898-900.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yue J, Zang X, Le Y, An Y. Anxiety, depression and PTSD among children and their parent during 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in China. Curr Psychol. 2022;41:5723-5730.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:1218-1239.e3.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang S, Xiang M, Cheung T, Xiang YT. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:353-360.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yeasmin S, Banik R, Hossain S, Hossain MN, Mahumud R, Salma N, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;117:105277.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Imran N, Zeshan M, Pervaiz Z. Mental health considerations for children and adolescents in COVID-19 Pandemic. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36:S67-72.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu JJ, Bao Y, Huang X, Shi J, Lu L. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:347-349.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:105-110.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang G, Zhang J, Lam SP, Li SX, Jiang Y, Sun W, et al. Ten-year secular trends in sleep/wake patterns in shanghai and Hong Kong school-aged children: A tale of two cities. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15:1495-502.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brazendale K, Beets MW, Weaver RG, Pate RR, Turner-McGrievy GM, Kaczynski AT, et al. Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: The structured days hypothesis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:100. [Crossref]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912-20.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jin B, Lee S, Chung US. Jeopardized mental health of children and adolescents in coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2022;65:322-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:20.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547-60.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Peña S, Watamura SE, Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110:104699.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meade J. Mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents: A review of the current research. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2021;68:945-959.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soni R, Upadhyay R, Jain M. Prevalence of smart phone addiction, sleep quality and associated behaviour problems in adolescents. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5:515-519.

- Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, Huang Y, Miao J, Yang X, et al. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:112-118.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu TC, Desai RA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Cavallo DA, Potenza MN. Problematic Internet use and health in adolescents: data from a high school survey in Connecticut. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:836-845.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lemola S, Perkinson-Gloor N, Brand S, Dewald-Kaufmann JF, Grob A. Adolescents' electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:405-418.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu Q, Zhou Y, Xie X, Xue Q, Zhu K, Wan Z, et al. The prevalence of behavioral problems among school-aged children in home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in china. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:412-416.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, Gong Y, Guan Z, Lou D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:36-38.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chien WH, Shih YN, Wang KH, Zheng WY, Wang CL, Shia BC, et al. Trend analysis of children's physical and mental health index in 2022. J Data Anal. 2023;18:75-97.

- Chien WH, Shih YN, Ting TI, Chuang CW, Chiang S, Chen YT, et al. Establishment and analysis of children's physical and mental health index. J Data Anal. 2022;17:59-89.

- Winfield A, Sugar C, Fenesi B. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of families dealing with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. PLOS ONE. 2023;18:e0283227.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pudpong N, Julchoo S, Sinam P, Uansri S, Kunpeuk W, Suphanchaimat R. Family health among families with primary school children during the COVID pandemic in Thailand, 2022. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:15001.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park H, Yu S. Paternal mental health and parenting in the COVID-19 pandemic era. J Mens Health. 2022;18:217.

- Bourion-Bédès S, Rousseau H, Batt M, Tarquinio P, Lebreuilly R, Sorsana C, et al.Mental health status of French school-aged children's parents during the COVID-19 lockdown and its associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:10999.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Chien WH, Chang HF, Wang KH, Shih YN, Tai YH, Chen MC, et al. (2024) Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Mental Health in Taiwan: 2021-2022, Two-Year Follow-up Study. J Trop Dis. 12:422.

Copyright: © 2024 Chien WH et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.