Indexed In

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2020) Volume 6, Issue 2

Impact of an Educative Workshop on Aspiration, Targeting Patients with Dysphagia, and Their Family Caregiver: A Randomized Pilot Study

Zahya Ghaddar1*, Puech M2 and Matar N32Rangueil, Toulouse, France

3Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery and Department of Speech and Language, Department of Speech and Language Pathology Saint- Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon

Received: 01-Jan-2020 Published: 12-Jun-2020, DOI: 10.35248/2573-4598.20.6.148

Abstract

Background: In swallowing rehabilitation, conventional methods for patient rehabilitation may be insufficient. Therapeutic Patient Education (TPE) may improve the results of these conventional techniques.

Aim of the study: This randomized pilot study aimed to assess the impact of an educative workshop designed for patients with dysphagia and their family caregivers, on adherence to swallowing rehabilitation and quality of life (QOL).

Methods: This workshop simultaneously targeted the understanding and explanation of aspiration, its clinical signs, and decisions regarding food consistency to avoid aspiration. In this randomized pilot study, the intervention was carried out on 16 patients for three months. The Experimental Group (EG) is comprised of 8 patients undergoing conventional swallowing rehabilitation and an educative workshop. The Control Group (CG) is comprised of 8 patients undergoing only conventional swallowing rehabilitation. The pre- and posttest evaluation of the impact of the workshop was based on four instruments: The Arabic-Dysphagia Handicap Index (A-DHI), items of the Caregiver Mealtime and Dysphagia Questionnaire (CMDQ), a questionnaire assessing knowledge linked to aspiration, and a QOL scale. For the CG, the posttest was conducted one week following the pretest. As for the EG, the posttest was conducted one week after the educative workshop on aspiration.

Results: Results showed a significant difference in the scores of the knowledge linked to the aspiration questionnaire. (p - value=0.002) and the QOL scale (p - value=0.04) for the EG only.

Conclusion: The preliminary results obtained are encouraging to continue this study. Future work is needed with a higher frequency of educative workshops, a higher number of patients and complete validation of the outcome measures.

Keywords

Therapeutic patient education; Dysphagia; Adherence; Quality of life; Family caregiver; Swallowing rehabilitation

Introduction

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia (OD) is a dysfunction in the process of the transportation of food from the mouth to the stomach while protecting the airway path [1]. This dysfunction may result in the passage of solid foods or liquids into the lungs if the pulmonary clearance mechanisms are absent [2], a phenomenon referred to as aspiration. Aspiration can lead to severe consequences such as malnutrition, dehydration and pneumonia [3,4]. Aspiration pneumonia has a high prevalence in OD patients. It is increased by a combination of poor oral health, oropharyngeal bacterial colonization, malnutrition and poor immune system [5]. Aspiration can have an impact on the quality of life of the patient and can sometimes lead to asphyxia and death [4,6].

Most patients with OD need rehabilitation provided by a multidisciplinary team comprising physicians, dietitians, nurses, psychotherapists, family caregivers and healthcare therapists [7,8]. Among this team, the swallowing therapist has a crucial role in screening, assessment, rehabilitation of dysphagia patients as well as educating the patients, their family caregivers and the healthcare team [9-11]. For the screening of the dysphagia patient, different tools can be considered, such as swallowing trials with or without oximetry and questionnaires to report dysphagia [12]. These may aid at identifying patients at risk for aspiration or unsafe swallowing as a step before further clinical assessment [4]. Additionally, the clinical assessment includes a clinical swallowing examination (CSE) in addition to videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES). In some countries, the instrumental evaluation is provided by an ENT doctor instead of the swallowing therapist [4]. Throughout the treatment, the swallowing therapist aims for the remediation of physiopathological mechanisms, by the application of exercises targeting the neuromuscular dysfunctions and the implementation of adaptive strategies, leading altogether to the partial or total regression of symptoms [4,13]. The treatment plan targets the safe feeding of the patient to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia [14]. Educating the patient and his family caregiver about the application of adaptive strategies, the rehabilitation exercises and the oral hygiene is within the therapist’s skills [14,15].

In our clinical practice, most of the difficulties faced are related to the comprehension, assimilation, and implementation of the swallowing therapist’s recommendations by patients and their family caregivers [16]. Dysphagia patients have difficulties adhering to swallowing rehabilitation for different reasons (e.g. lack of conviction of their need for adapted consistencies for food and specified postures, lack of adherence to the proposed exercises, patients willing to take the risk of complications while sticking to eat regular foods, lack of support, resources and time…) [6,16-19]. Nowadays, an educative approach consisting of Therapeutic Patient Education (TPE) [as used by the European researchers, cited as "patient education" in the scientific studies or as a "self-management program" as used in the American literature] is available to patients, enabling them to respond to occurring difficulties. This approach has demonstrated its effectiveness on the well-being of patients in chronic diseases since the 1970s [20] and in the rehabilitation of patients with chronic pathology (diabetes, asthma, obesity...) by improving their adherence to their rehabilitation. Dysphagia is also a chronic symptom and has an impact on the patient's state of health and quality of life. The integration of patients into a specific TPE program for swallowing disorders started in the 2000s within healthcare structures (hospitals, private clinics) and at the patient’s home with the help of an adequate mobile team of rehabilitation [21]. Swallowing therapists of healthcare structures are included in these programs. The TPE program would involve several workshops with complementary targets. Therefore, this pilot randomized controlled trial aimed to study the benefits of an educative workshop focusing on aspiration, on adherence of dysphagia patients and their family caregivers to rehabilitation and the patients' quality of life by answering a series of research questions.

Research questions

1. Does the implementation of the educative workshop improve the knowledge linked to aspiration by the pair patient/family caregiver?

2. Does the implementation of the educative workshop allow an improvement of adherence of the pair to the speech therapy rehabilitation?

3. Is the improvement of the adherence to the speech therapy rehabilitation by the pair linked to the improvement of the quality of life of the patient?

4. Does the improvement of knowledge linked to aspiration by the pair help in improving the quality of life of the patient?

Material and Methods

Participants

The study protocol received the approval of the Hotel Dieu de France Hospital/St Joseph University Ethics Committee (Ref: 2016/13) applying the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. A total of 16 patients and their family caregivers (family members and/or significant other) signed informed consent to participate in this pilot randomized study. These patients were followed by different swallowing therapists; they were selected in compliance with the following inclusion criteria:

- A patient diagnosed with dysphagia, present during the sessions and the intervention with their family caregiver.

- A patient undergoing swallowing rehabilitation.

- Patients aged 18 years old and above.

- Family caregivers spending more than 6 hours per day with the patient.

Patients were excluded from this study if they matched these exclusion criteria:

- At the beginning of the study, the patient with dysphagia showed signs of cognitive impairment and his family caregiver is illiterate.

- During the study, the patient with dysphagia discontinued the swallowing rehabilitation sessions.

The random sequence was computer-generated. Hence, participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups: an experimental group and a control group. The experimental group was composed of 8 patients and their family caregivers following conventional swallowing rehabilitation and one session of the educative workshop. The control group was composed of 8 patients and their family caregivers following conventional swallowing rehabilitation. The recruitment of the patients and their family caregivers was done between February and April 2016. Both groups followed a conventional swallowing rehabilitation twice per week for 45 minutes by different swallowing therapists.

Intervention

Procedure: The educative workshop sessions were administrated by the same swallowing therapist and lasted 45 minutes targeting three axes:

(i) The explanation of the aspiration by watching 4 short videos (on the iPad) showing (1) the normal swallowing process,

(2) laryngeal penetration with a cough, (3) tracheal aspiration with a cough and (4) silent aspiration without a cough by using an application called “aspiration disorders-blue tree publishing, Inc.” on the iPad.

(ii) The different clinical signs by using Barrow cards [22], which constitute a teaching tool presenting a simulation mean where situations and resolutions of these situations occur. Proposed decisions are either relevant (positive), non-effective (neutral) or aggravating (negative) situations. Each decision is numbered and corresponds to a card, on the back of which are described the consequences of the chosen decision. This progression between the situation, the choice of decision and the corresponding consequence makes it possible to conduct a decision-making process. The construction of this tool is long, so an equivalent by computer programs is possible. Barrow cards were designed for chronic diseases and have been used in individual education of asthmatic patients [22]. In our study, 21 Barrow cards were created using a PowerPoint document. Among its 21 slides, 7 slides presented situations where signs of aspiration occur, each situation illustrating a sign of aspiration (1) throat cleaning, (2) wet voice without a cough, (3) wet voice with a cough, (4) pneumonia, (5) unexplained fever, (6) food blockage and (7) extended mealtime. Each situation was subject to three choices (right, wrong, neutral behaviors) of the adopted behavior of the patient/family caregiver, and each choice was related to the consequence of the chosen behavior. These three choices were presented with visual and auditory support (green light with a positive sound when the right behavior is chosen by the patient/family caregiver, red light with a negative sound when the wrong behavior is chosen, orange light with a neutral sound when the behavior chosen is neutral).

(iii) The decision upon the choice of the right consistency of food and beverage preventing aspiration by using a tray with real food at different meals (starters: season salad, lentil soup, steamed vegetables, and mashed potato; main dishes: dried tuna, green peas stew with rice and minced meat, steak, chicken breast; breakfast & dinner: boiled egg, labneh (Lebanese white creamy cheese), local bread, Greek yogurt, thyme manoushe (Lebanese pizza); deserts: biscuits, custard, sponge cake, applesauce, banana, apple, orange; and beverages: coffee, fruit nectar, sparkling water, still water, thickened water). The patient/family caregiver should know which consistency of food or beverage to choose according to the swallowing therapist recommendations. If the patient included in the study wasn’t treated by the swallowing therapist conducting the study, a meeting was set with the entitled swallowing therapist to verify the right choice of consistencies by the pair patient/family caregiver.

Some adaptations and repetitions were needed during the intervention like using simple vocabulary and sentences while explaining and watching the 4 videos related to aspiration. Additionally, the different choices related to the Barrow cards required examples and repetitions for the patients and their family caregivers. Further details of the intervention are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Outcome measures

The impact of the educative workshop was evaluated by comparing pre- and posttest scores of 3 questionnaires and 1 scale

- The Arabic-Dysphagia Handicap Index (A-DHI) [23] assessing handicap perception,

- Items of the Caregiver Mealtime and Dysphagia Questionnaire (CMDQ) [24] assessing the adherence to the rehabilitation,

- A questionnaire in standard Arabic assessing knowledge linked to aspiration ad-hoc [25],

- A QOL scale [22].

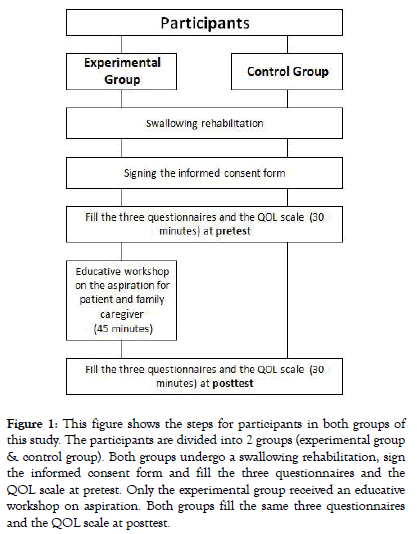

The pretest was conducted for the EG before the use of the educative workshop. The posttest was conducted one week after the educative workshop. As for the CG, the pretest evaluation was conducted immediately after signing the informed consent form, and one week after signing for the posttest. Figure 1, presents the steps for patients in both groups of this study.

Figure 1: This figure shows the steps for participants in both groups of this study. The participants are divided into 2 groups (experimental group & control group). Both groups undergo a swallowing rehabilitation, sign the informed consent form and fill the three questionnaires and the QOL scale at pretest. Only the experimental group received an educative workshop on aspiration. Both groups fill the same three questionnaires and the QOL scale at posttest.

The first questionnaire “Arabic Dysphagia Handicap Index, A-DHI [23] is an auto-administrated questionnaire that evaluates the patient’s perception of handicap. If the patient demonstrates a cognitive impairment, the questionnaire was filled by the family caregiver. This questionnaire is composed of 25 questions scoring between 0 and 100, (the higher the score, the higher is the severity of dysphagia).

The second questionnaire CMDQ [24] is composed of 33 questions that assesses the adherence to the swallowing rehabilitation and was filled by the family caregiver. This questionnaire was validated in the USA to evaluate the reasons for the non-adherence of caregivers to swallowing therapist recommendations and the difficulties that occur concerning the patient's quality of life. This questionnaire was translated into Arabic after the approval of the author. Three bilingual swallowing therapists translated the questionnaire to Arabic resulting in three translated versions of the same questionnaire. Then, a fourth version was realized relying on the most used terms. Afterward, a certified translator completed the backward translation of the fourth version into English to verify if the terms used in Arabic meet the adequate meaning in English. This backward translation proved its accuracy. The last version was verified by a bilingual phoniatrician before its use. The validation of the questionnaire is still an ongoing process. In this study, only 8 questions evaluating the disagreement with Speech- Language Pathologist (SLP) as mentioned by Colodny (2008) (questions 8, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 & 22) were used. Out of these questions, we chose 5 questions (8. I am not sure whether my fm/ so is on thickened liquids, 19. I am not sure which specific feeding techniques to use (e.g., double swallow and small boluses were given slowly), 20. I don't have time to follow through on swallowing recommendations given by the Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP), 21. It is not necessary to give my family member/significant other (fm/so) small amounts and wait between mouthfuls and sips & 22. I don’t understand why specific feeding techniques were recommended by the SLP) which have the same type of sentence so we can calculate the mean of the score in the same way.

The third questionnaire evaluated the knowledge of patient and family caregiver about aspiration (Appendix A), it is inspired from Ilott et al. (2014) study [25] and the dysphagia game of Nutricia [26]. The validation of the questionnaire is still an ongoing process. It is composed of 10 YES/NO questions, out of which 5 are correct and 5 are false. This questionnaire was translated into Arabic and was auto-administrated by the patient. In case the patient presented a cognitive impairment, the family caregiver filled it. Furthermore, if the patient was illiterate, the swallowing therapist offered assistance.

Finally, a scale of QOL inspired by the scale of semantic differentiation of Osgood [22] (Appendix B) was translated to Arabic. It is composed of 6 levels from 0 to 6 (0 = the lowest level, 6 = the highest level). The family caregiver should choose the number that qualifies the QOL of the patient. The validation of the scale is still an ongoing process.

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis, “IBM SPSS Statistics Base v20.0” was applied.

Parametric tests were used for variables following a normal distribution law. The “Independent T-test” was used to measure the homogeneity of results of both groups (experimental and control) at pretest and posttest. The “Paired sample T-test” was used to compare each group (experimental and control) at pretest and posttest. Correlation between quantitative variables was assessed by using the parametric Pearson correlation coefficient to compare both group (experimental and control).

Non-parametric tests were used for variables that don’t follow a normal distribution law. The “Mann-Whitney U” was used to measure the homogeneity of results for both groups (experimental and control) at pretest and posttest. “Wilcoxon” test was used to compare each group (experimental and control) at pretest and posttest.

A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant with a confidence interval of 95%

Results

Demographics

Patients' demographics in the EG and CG are reported in Table 1. Sixteen patients with OD along with their family caregivers completed the study. Different causes of dysphagia were presented, stroke having the highest percentage within both groups. The swallowing rehabilitation duration was divided into two ranges, over one month and less than one month. Feeding was done either orally, non-orally or both.

Table 1: Patients demographics.

| Variable | Control Group | Experimental Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Sex | ||||

| F | 4 | 50 | 3 | 37.5 |

| M | 4 | 50 | 5 | 62.5 |

| Age | ||||

| Between 18-45 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Between 46-60 | 1 | 12.5 | 2 | 25 |

| Above 61 | 6 | 75 | 6 | 75 |

| Cause of dysphagia | ||||

| Stroke | 4 | 50 | 3 | 37.5 |

| Parkinson | 0 | 0 | 2 | 25 |

| Alzheimer | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Esophageal dysphagia | 2 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| FTD | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Encephalitis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| PSP | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| SR duration | ||||

| Less than 1 month | 5 | 62.5 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Over 1 month | 3 | 37.5 | 7 | 87.5 |

| Feeding type | ||||

| Orally | 7 | 87.5 | 5 | 62.5 |

| Non-orally | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Both | 1 | 12.5 | 2 | 25 |

Note. F: Female; M: Male; FTD: Frontotemporal dementia; PSP: Progressive supranuclear palsy; SR: Swallowing Rehabilitation.

Functional outcomes

We verified the homogeneity of both groups (CG and EG) at the pretest of all the scores (Table 2). Starting with the questionnaire evaluating the knowledge linked to aspiration, it showed a nonsignificant difference in both groups ( p − value = 0.74) . The difference was also non-significant for the 5 items of CMDQ evaluating the adherence ( p − value = 0.19) , the QOL scale( p − value = 0.19) , and the A-DHI ( p − value = 0.46) . We compared the scores between groups (CG and EG) in the posttest on all the questionnaires and the scale (Table 3). The questionnaire evaluating the knowledge linked to aspiration showed a significant difference between both groups ( p − value = 0.01) however, the difference wasn’t significant for the 5 items of CMDQ evaluating the adherence ( p − value = 0.42) , the QOL scale( p − value = 0.42) , and the A-DHI evaluating the perception of handicap ( p − value = 0.008) .

Table 2: Scores of the questionnaires and scale at pretest for both groups.

| CG Pretest | EG Pretest | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M | M | ρ | |

| Knowledge linked to aspiration | 6.25 | 6.50 | .74 |

| CMDQ | 11.38 | 9.75 | .40 |

| QOL scale | 3.63 | 2.88 | .19 |

| A-DHI | 47 | 40 | .46 |

*p-value<0.05; M=Mean.

Table 3 Scores of the questionnaires and scale at posttest for both groups.

| CG | EG | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Posttest | Posttest | ||

| M | M | ρ | |

| Knowledge linked to aspiration | 6.38 | 7.88 | 0.01* |

| CMDQ | 11.00 | 9.50 | 0.42 |

| QOL scale | 4.00 | 3.50 | 0.42 |

| A-DHI | 46.75 | 36.5 | 0.29 |

*p-value<0.05; M=Mean.

The comparative analysis of the results obtained in the pretest and posttest within each group (Table 4) showed no improvement in the scores of all outcomes measures in the CG. As for the EG, the effectiveness of the educative workshop lies in the knowledge of aspiration and the QOL.

Table 4 Scores of the questionnaires and scale at pretest and posttest for both groups.

| CG | EG | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | Posttest | Pretest | Posttest | |||

| M | M | ρ | M | M | ρ | |

| Knowledge linked to aspiration | 6.25 | 6.38 | 0.88 | 6.50 | 7.88 | 0.002* |

| CMDQ | 11.38 | 11.00 | 0.65 | 9.75 | 9.50 | 0.87 |

| QOL scale | 3.63 | 4.00 | 0.19 | 2.88 | 3.50 | 0.04* |

| A-DHI | 47 | 46.75 | 0.95 | 40 | 36.5 | 0.38 |

*p-value<0.05; M=Mean.

We studied the correlation between the knowledge linked to aspiration and the QOL. Pearson coefficient didn’t show a correlation, both variables are independent, (p-value=.15). We also studied the correlation between adherence to swallowing rehabilitation and QOL. Pearson coefficient showed that both variables are dependent (p-value = .05) and Pearson coefficient correlation r (8) = .7 shows that a positive and strong correlation exists between both variables.

Discussion

In our present study, we compared the impact of an educative workshop inspired by the TPE programs on the adherence of dysphagia patients and their family caregivers to the swallowing rehabilitation plan and on the patients' quality of life using an RCT design. At the pretest, both groups (CG & EG) had no significant difference in scores to the four outcomes measurement tools, which demonstrates that both groups had homogenous results at the beginning of the study.

Our study showed that the scores of the EG (Table 4) on the questionnaire evaluating the knowledge linked to aspiration improved after watching the 4 short videos by using the application called “aspiration disorders-blue tree publishing, Inc.” on the iPad and using the 21 Barrow cards. The comparative analysis of scores within both groups showed the positive effect of the intervention. These results seem fairly robust compared to those found in Woisard & Soriano study: where they performed a TPE linked to swallowing disorders but the results didn’t seem conclusive [27,28]. The score of the questionnaire of knowledge linked to aspiration of the EG was statistically significant at posttest ( p − value = 0.008) which meets what is published in the literature about the importance of TPE in improving the knowledge of patients [25].

The comparative analysis didn’t show an improvement in adherence to swallowing rehabilitation within both groups at pretest/posttest and between both groups at posttest to the 5 questions used from the CMDQ. This lack of evidence of improvement in adherence could be related to the excessive length of the CMDQ and the complicated type of questions which was highlighted by the family caregivers. Therefore, we looked at the results among the 8 family caregivers of the EG, 3 presented better scores of adherence to swallowing rehabilitation. They attained better scores to the first question (Q8. I am not sure whether my fm/so is on thickened liquids) especially given that the patients used oral or both types of feeding (oral and non-oral) and thickened liquids being among the recommendations given by the swallowing therapist. Therefore, our third axes "the decision upon the choice of the right consistency of food and beverage causing aspiration by using a tray with real food as different meals" could have contributed to the improvement in adherence to these family caregivers.

Another factor that could have affected non-adherence is the refusal of using thickener (62.5% of patients of the EG had food intake orally (Table 1)). This meets the idea found in the literature, the lack of adherence can be related to the dissatisfaction with the change of food texture [28], given that the availability of only a single product of thickener exists in Lebanon compared to other countries which restrain the participant’s choices. [28]. Knowing that the results aren't conclusive, further studies should take place including a higher number of participants to evaluate adherence to swallowing rehabilitation, using a simple, easy and short questionnaire. Moreover, it’s important to tailor the workshop according to the participant’s needs deduced from the educational diagnosis interview and to repeat it several times to verify whether this repetition would lead to better support of the family caregiver [29].

The QOL of the CG didn’t show a significant difference between pretest and posttest ( p − value = 0.04) Nevertheless, the QOL of the EG had a significant difference between pretest and posttest ( p − value = 0.04) This could be related to the fact that EG underwent the educative workshop and the fact that 87.5% (Table 1) underwent the educative workshop in addition to the swallowing rehabilitation for more than one month compared to the CG where only 37.5% underwent swallowing rehabilitation for more than one month without the educative workshop. Hence, the improvement of the QOL of the EG could be linked to the care provided by the swallowing therapist combined with the educative workshop as mentioned in the literature [30].

Concerning the comparison between the CG and the EG at the posttest, the difference isn’t significant. This could be related to the heterogeneous scores of the EG at the scale of QOL at the posttest. Therefore, to confirm these results further studies should be undertaken while increasing the number of participants. Besides, the duration of the swallowing rehabilitation should be controlled and unified among participants as an inclusion criterion in the study.

The absence of difference in the perception of handicap using A-DHI within both groups at pretest/posttest and between both groups at posttest could be due to the restricted amount of time between pretest and posttest. Thus, improved knowledge and the quality of life did not allow for a change in the perception of the handicap within a limited time.

The correlation between QOL and knowledge was not significant. Knowing that this correlation exists clinically, we noted that this mismatch between the clinical reality and the results obtained could be due to the restrained size of the sample of the study. A relation is confirmed between the adherence to ST rehabilitation and the QOL of the patient. In other words, the more the patient is seriously engaged in therapy, the more the chances are to perceive a better QOL. This leads to the conclusion that the implementation of the swallowing therapist recommendations yields an improvement in the patient QOL. These results are not different from the data found in the literature; the application of the swallowing therapist recommendations improves the QOL [25].

Limitations and Future Directions

The restricted size of the sample chosen highlights a major drawback. Despite all efforts made, we were not able to recruit more than 16 participants, a fact that could justify some non-significant results and shows also that results may not be generalizable to all patients with dysphagia. Moreover, some of the outcome measures lack formal evaluation of psychometric properties. It should be noted though, that despite the samples restricted size, we were still able to obtain significant scores concerning the evaluation of knowledge linked to aspiration and the QOL. It would be interesting to resume this study with a larger sample size to verify the impact the workshop would have on both the patient and the family caregiver’s knowledge simultaneously and separately. It would also allow for the verification of the relation between the perception of the handicap (from both patient and family caregiver points of view) and the QOL. The disparities in scores could be explained by the fact that different swallowing therapists were responsible for the conventional practices of the ST rehabilitation; the patients were recruited at different times and the variable nature of treatment locations all the while not encompassing the same multidisciplinary teams. Additionally, the difference in conventional swallowing rehabilitation treatment duration between both groups, with a longer duration for EG, could justify the improvement of EG scores. As already mentioned, the extension of the study, as well as the inclusion of a larger sample of participants, are necessary to demonstrate the impact of the educative workshop on adherence as well as the influence adherence has on the QOL. Hence, swallowing rehabilitation should be delivered by the same swallowing therapist in both groups with the same therapeutic principles and background with the only difference being whether the workshop is being applied or not during the same period of the swallowing rehabilitation. Besides, the duration of the swallowing rehabilitation should be homogenous for all the participants in the study. The family caregiver found two disadvantages related to the CMDQ questionnaire evaluating the adherence to the swallowing rehabilitation: the questionnaire was lengthy and the writing style and structure were difficult to understand, therefore an easy and accessible questionnaire should be created to evaluate the adherence of the family caregiver. Additionally, the workshop should be repeated several times to verify whether this repetition would lead to better support of the family caregiver. The design of the intervention should be tailored to the needs of the participants revealed in an educational diagnosis filled in before the beginning of the intervention. Moreover, these workshops adapted to the swallowing rehabilitation practice, could be standardized and made available to swallowing therapists involved in the rehabilitation of dysphagia patients to form an integral part of swallowing rehabilitation of the dysphagia patient and his family caregiver.

Conclusion

The influence of educative workshops on patients in swallowing rehabilitation is far from negligible on the daily life of dysphagia patients, but their use is not systematic. There’s still no high level of evidence of the benefit of this educative workshop, it is nevertheless clearly visible at some levels. The preliminary results showing improvement of the knowledge linked to aspiration and the QOL are encouraging to continue this study. Future work is needed with a higher frequency of educative workshops, a higher number of patients and complete validation of the outcome measures.

REFERENCES

- Logemann JA. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. Texas: Proed. 1998.

- Rommel N, Shaheen H. Oropharyngeal dysphagia: Manifestations and diagnosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol. 2016;11.

- Chadwick DD, Jolliffe J, Goldbart J. Adherence to eating and drinking guidelines for adults with intellectual disabilities and dysphagia. Am J Ment Retard. 2003;108.

- Speyer R. Oropharyngeal Dysphagia. Otolaryng Clin N Am. 2013;46:989-1008.

- Clavé P, Shaker R. Dysphagia: Current reality and scope of the problem. Nat Rev Gastroenterol. 2015;12:259-270.

- Chadwick DD, Jolliffe J, Goldbart J, Burton MH. Barriers to Caregiver Compliance with Eating and Drinking Recommendations for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities and Dysphagia. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2006;19:153-162.

- Bleeckx, D. Dysphagia - Evaluation and rehabilitation of swallowing disorders. Brussels: de Boeck University. 2002.

- Woisard-Bassols V, Puech M. Rehabilitation of swallowing in adults. Update on functional management. Marseille: Solal. 2011.

- Colodny N. Construction and Validation of the Mealtime and Dysphagia Questionnaire: An Instrument Designed to Assess Nursing Staff Reasons for Noncompliance with SLP Dysphagia and Feeding Recommendations. Dysphagia. 2001;16:263-271.

- Kremer JM, Lederlé E. Speech therapy in France: What do I know? No. 2571. University Presses of France. 2016.

- Roth FP. Treatment resource manual for speech-language pathology (5thedn), Cengage Learning. 2014.

- Park YH, Bang HL, Han HR, Chang HK. Dysphagia Screening Measures for Use in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2015;45:1.

- Ekberg O. Dysphagia: Diagnosis and Treatment. Springer International Publishing. 2019.

- Langmore SE, Terpenning MS, Schork A, Chen Y, Murray JT, Lopatin D. Predictors of Aspiration Pneumonia: How Important Is Dysphagia? Dysphagia. 1998.13:69-81.

- Cichero DJ. Project Consultant and Editor. 2012;21.

- Krekeler BN, Broadfoot CK, Johnson S, Connor NP, Rogus-Pulia N. Patient Adherence to Dysphagia Recommendations: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia. 2018;33:173-184.

- Colodny N. Determinants of noncompliance of speech-language pathology recommendations among patients and caregivers. Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders. 2007.

- Colodny N. Dysphagic Independent Feeders’ Justifications for Noncompliance with Recommendations by a Speech-Language Pathologist. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2005;14:61-70.

- King JM, Ligman K. Patient Noncompliance With Swallowing Recommendations: Reports From Speech-Language Pathologists. CICSD. 2011;38:53-60.

- Lacroix A, Assal JP. Therapeutic patient education: Supporting patients with a chronic disease: new approaches (3rd edition revised and completed). Paris, France: Maloine. 2011.

- Patient Hospital Health and Territory Educational support for the HPST law, (2009) Ministry of health and sports, France. p:51.

- D’Ivernois JF, Gagnayre R. Learn to educate the patient. Educational approach. (4th edition). Paris, France: Maloine. 2011.

- Farahat M, Malki KH, Mesallam TA, Bukhari M, Alharethy S. Development of the Arabic Version of Dysphagia Handicap Index (DHI). Dysphagia. 2014;29:459-467.

- Colodny N. Validation of the Caregiver Mealtime and Dysphagia Questionnaire (CMDQ). Dysphagia. 2008;23:47-58.

- Ilott I, Bennett B, Gerrish K, Pownall S, Jones A, Garth A. Evaluating a novel approach to enhancing dysphagia management: workplace-based, blended e-learning. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:1354-1364.

- Nutricia. The Dysphagia Game. 2014.

- Woisard V, Soriano G. From the theory to practice. Therapeutic patient education and swallowing disorders. Sante Education Journal of the Afdet French Association for the development of therapeutic education. 2012.

- Tymchuck D. About food and beverage thickener agents. 2013.

- Fredericks S, Guruge S, Sidani S, Wan T. Postoperative Patient Education: A Systematic Review. Clin Nurs Res. 2010;19:144-164.

- McKinstry A, Tranter M Sweeney J. Outcomes of Dysphagia Intervention in a Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program. Dysphagia. 2010;25:104-111.

Citation: Ghaddar Z, Puech M, Matar N (2020) Impact of an Educative Workshop on Aspiration, Targeting Patients with Dysphagia, and Their Family Caregiver: A Randomized Pilot Study. J Pat Care 6:148.

Copyright: © 2020 Ghaddar Z, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.