PMC/PubMed Indexed Articles

Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Academic Keys

- JournalTOCs

- ResearchBible

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2021) Volume 0, Issue 0

Health and Social Rights of Older Adults in Continental Central America: A Comparative Historical and Legal Analysis

Roberth Steven Gutiérrez-Murillo*Received: 08-Dec-2021 Published: 29-Dec-2021

Abstract

This work is part of contemporary discussions on the multidimensional impacts of the phenomenon of population aging. Thus, it intends to feed the debate on aging and its legal and health determinants, taking as unit of analysis the Central American (hereafter CA) continental region. A documentary and normative analysis of the legal instruments that defend the fundamental rights of CA older adults was carried out. Therefore, this text presents a detailed comparison of state interventions in these countries, insofar as it addresses national laws and policies on aging, and their discrepancies in the region. It was concluded that, in addition to the current internal regulations aimed at promoting comprehensive care for aging populations in CA, the health actions for the older persons find strong state support, backed by single texts in the political constitutions in some CA territories.

Keywords

Aging population; Demographics; Social policies; Public health

Introduction

This work is part of contemporary discussions on the multidimensional impacts of the phenomenon of population aging. Thus, it intends to feed the debate on aging and its legal and health determinants, taking as unit of analysis the Central American (hereafter CA) continental region. From the outset, it is recognized that addressing the issue of demographic dynamics is a broad challenge, mainly because it goes through different theories and gerontological paradigms, which makes this debate quite pluralized. Studies on population aging seem to focus on two main points. In the first case, there is an international interest in quantitatively measuring (through coefficients, indexes and rates) the implications of diseases predominant in old age and their immediate effects on the functioning of public health and social assistance systems. Grounded on this, other studies seek, from this first point, to question the state position in protecting and ensuring the fundamental rights of older adults, advocating for the promotion of active aging, socially engaged and with a greater degree of autonomy. In both cases, such studies concentrate importance and should be taken as starting points in the proposition of current gerontological analyses.

In this scenario, the question regarding the conception of health and its determinants arises. According to the World Health Organization-WHO, 'health' is considered as the state of physical, mental and social well-being of the individual, pointing to the discovery and improvement of soft, medium and hard technologies that provide better care conditions for people in their (inter) relationships [1]. Nonetheless, such concept is perceived as limited since it does not take into account the various determinants of health based on this very concept. This inflection is not asked today, as for decades scholars have been criticizing it, putting on the table its limited scope and validity in contemporary times. Citing for example, Serge [2] comments that to think of health simply as a state of physical, mental, and social well-being is to perceive health in an outdated manner, because in order to understand health in an expanded and humanized way, several aspects perceived through the lenses of comprehensive and interdisciplinarity in health must also be glanced, linking all possible factors affecting health to the multifactorial and multisectoral analysis.

It is a matter of fact that the realization of health as a fundamental right of individuals has become an eminent obstacle for developed nations and, especially, for developing ones that seek to structure fair societies, which is why it is interesting to assist the case of CA States. Behold, the study on the fundamental rights of older adults extends from the physiological point, which concerns the forms of health care on the main pathologies that affect their organic and functional profile offered by health systems in the spheres of micro and macro management, to the socio-sanitary point, arguing the characteristics of the environment and the social determinants of health, such as, for example, access to basic services, employment, education, social security/retirement, citizen participation and fair insertion in the economic market, among others.

In this sense, States consent to the fact that aging is an irreversible process and that, in order to promote healthy and dignified living conditions in old-age, the materialization of these fundamental rights becomes essential, in the form of norms and instruments, both in the internal (national) and external (international) scopes, that consecrate harmony between the health sector and the legal sector, to the extent that an active legal-health dialogue is proposed, taking into consideration the socio-health profile of each nation. Therefore, it is evident that advances in legal-health issues in the area of elderly health represent demystifying intervention from conceptions geared on the pathological nature of aging and in partnership with other social sciences, welcoming the task of defending the fundamental rights that correspond to the elderly, through the exposure of social-sanitary inequities, the divergence of the degree of accessibility to health systems and services, and the differentiated protection of the right to health in old-age.

Consistent with the notes of Melo et al., it is understood that State action is the object of public policies [3]. Thus, the actions, operating mechanisms, and their likely impacts are the focus of studies that aim to analyze a certain policy. This requires, according to the authors, the ability to understand singularities related not only to the explicit content of the policy as such (corpus), but also to the evolution, modification and innovation of the policy of interest. In particular, this study is concerned with understanding the (inter)relationship between the legal system (with respect to the ordering of internal rules) and the health system (referring to the forms of organization and care of the health demands of the elderly in CA).

In a provocative tone, we ask: what is the degree of legal protection for the health of older adults in CA? And, as part of this study, we ask: what do national health policies for the elderly tell us in this region? In order to provide answers to these questions, this study sought to examine the legal and health framework, through a comparative analysis of the national health older adults in CA. Consequently, and in order to nourish the corpus of this work, it briefly addresses integration processes of the Central American regional bloc, analyzing political parties in these countries.

Materials and Methods

This is an empirical analysis with a qualitative and analytical- descriptive approach, typified by the mixed method of documentary and bibliographic review. According to the guidelines postulated by Fontelles et al., the bibliographic research provides analysis of published scientific material and the documentary research the collection of primary or secondary data [4].

The choice of mixed typification was due to the free availability of digital documents, which can be accessed immediately by consulting the official sites of the CA countries via the Internet, and also to the academic productions made available in the same way in high-impact academic journals linked to the health area or purposes. The selection and procurement of official documents was carried out virtually, through online consultation of the official websites of the Ministries of Health in each country. Thus, the document review method had advantages in this qualitative research, since it facilitated the immediate obtaining and analysis of materials, simply by having access to the virtual network and the reviewed data.

A full reading of the national health policies for older adults of each country (when available) was performed, followed by an analytical comparison of the internal regulations, which sought to identify the degree of legal protectionism of the right to health of older adults in CA. The empirical analysis of the contents allowed the proposal of Andrade et al., using the Thematic Analysis, which focuses on considering the text as a fully linguistic and historical object that, when explored, led to the emergence of empirical categories of analysis, with their respective themes, which served as a reference for the inferential process and the interpretation of the results in the theoretical framework of Public Policies on Health of the older people in CA countries [5].

The information provided in this paper has been grouped into three parts. Thusly, Part I presents a brief description of the integration processes experienced by Central American countries since the 1980s. As followed, Part II discusses the issue of the right to health through the geronto-sanitary approach, extending the debate to national policies for the health of the elderly and the specific norms for the protection of the elderly. Part III, on the other hand, provokes reflection on the contemporary challenges and future geronto-sanitary perspectives of the CA region.

Since this study analyzed secondary data openly available on the Internet, the need to obtain the approval of a Research Ethics Committee for the development of this study was not considered.

Results and Discussion

Part I: Path to central American regional integration

CA is the region with the lowest population density and smallest territorial extension of the American Continent. Also called 'Mesoamerica', it is constituted by seven nations, namely: Panama; Costa Rica; Nicaragua; Honduras; El Salvador; Belize and Guatemala. The Spanish language is predominant in the region, as Belize is the only English-speaking country. The region has great geographical diversity, both natural and geo-economic, and its location makes it a bridge connecting the northern and southern regions of the continent. The Catholic religion, being the most popular theological strand in the region, was a direct inheritance of the colonial processes that left the former Kingdom of Spain in such territories.

It is possible to notice that throughout the 21st century, especially since the middle of the century, nations have been working on the idea of integration and taking an interest in CA regional development. In 1951, in particular, in the capital city of San Salvador, the creation of the Organization of Central American States (from Spanish Organización de Estados Centroamericanos – (ODECA) was enacted through the Protocol of Tegucigalpa, basing its creation on the indestructible bonds of brotherhood, for the progressive development of its institutions, the protection of its collective interests, and the resolution of the region's problems. But what would an Integration System be? What can be expected from it? In order to answer such provocations, Segura reflects: Integration Systems, in general terms, are aimed at taking advantage of opportunities for countries to act as a bloc before others with whom they have a commercial or international policy relationship [6]. However, the action must allow the citizens, integrated into a system, to count on tangible benefits so that they can continue to support the integrationist efforts with their resources. In other words, the opportunity cost of managing a series of budgetary, human, material, and capacity resources installed in the System must have a greater counterbalance than directing it toward internal programs or public policies [6-12].

On December 13, 1991, the Central American Integration System (from Spanish Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana-SICA) was created: The System was conceived taking into account previous experiences for the integration of the region, as well as the lessons bequeathed by the historical facts of the region, such as political crises and armed conflicts, and the conquest of entities and instances before SICA, now part of the organization. Based on this, and considering the internal constitutional transformations and the existence of democratic regimes in CA, it was established as a fundamental objective the achievement of Central American integration to constitute it as a region of peace, freedom, democracy, and development, firmly based on the respect, protection, and promotion of human rights [7]. The concern for the attention and accompaniment of the social needs and demands of the region was collectively materialized by the countries in 1995, through the Treaty of Central American Social Integration (from Spanish Tratado de la Integración Social Centroamericana), also known as the ‘Treaty of San Salvador’, which served as the foundation for the creation of the Secretariat of Central American Social Integration (from Spanish Secretaría de la Integración Social Centroamericana- SISCA. At that moment the countries parties enacted the common commitment to: (Art. º 1) to achieve, in a voluntary, gradual, complementary, and progressive manner, the social integration of Central America, with a view to promoting greater opportunities and a better quality of life and work for the Central American population, ensuring their full participation in the benefits of sustainable development, and (Art. º 2) to implement a series of policies, mechanisms, and procedures that, under the principle of mutual cooperation and supportive solidarity, guarantee both access to basic services for the entire population and the potential development of Central American men and women, based on overcoming the structural factors of poverty, which affect a high percentage of the population of the Central American region; (Art. º 7, Inc. "b") to achieve regional conditions of well-being, social and economic justice for the people, within a broad regime of freedom that guarantees the full development of the person and of society; (Art. º 7, Inc. "e") to promote equal opportunities for all people, eliminating discriminatory practices of a legal or legal nature and (Art. º 7, Inc. "f") to promote, as a priority, investment in the human person for his or her comprehensive development [8]. The integrationist vision of the CA countries depended on being essentially oriented on a base of principles with internal and external force, which would justify the common actions of the states and that, in such an understanding, their real effectiveness would be perceived not only by the decree of such, albeit the immediate group compliance. The principles of social integration adopted by CA countries in 1995 are shown in Table 1.

| Item | Principles |

|---|---|

| A | Respect for life in all its manifestations and the recognition of social development as a universal right; |

| B | The concept of the human person, as the center and subject of development, which requires a comprehensive and articulated vision among its various aspects, in order to enhance sustainable social development; |

| C | The consideration of the family as the essential nucleus of society and the axis of social policy; |

| D | The encouragement of peace and democracy, as basic forms of human coexistence; |

| E | Non-discrimination on the basis of nationality, race, ethnicity, age, infirmity, disability, religion, sex, ideology, marital or family status, or any other type of social exclusion; |

| F | Living in harmony with the environment and respecting natural resources; |

| G | The punishment of all forms of violence; |

| H | The promotion of universal access to health, education, housing, leisure, as well as to dignified and fairly remunerated economic activity; |

| I | The maintenance and rescue of cultural pluralism and the ethnic diversity of religion, within the framework of respect for human rights; |

| J | The activesupport and inclusion of community participation in the management of social development. |

Source: SICA [8]. Own elaboration (2021).

Table 1: Main principles according to Treaty of CA Social Integration, 1995.

The aforementioned principles embrace social rights-now considered as fundamental-and have strong characteristics of the social control mechanism. To this matter, Sposati and Lobo [9:366], point out that social control analyzed through the democratization of health policies, is considered as a field that made visible the efforts of health movements, either by denouncing the "absences and omissions" of the installed services, or by fighting to build a regular space for the exercise of control over services and the bureaucracy of health management. The main objective of the SISCA is to foster the coordination of intersectoral social policies among SICA member States and integration bodies, establishing regional agendas to address common sustainable development challenges in CA and the Dominican Republic. Therefore, SISCA's main function is to "ensure, at the regional level, the correct application of the Treaty and other legal instruments of regional social integration and the execution of the decisions of the bodies of the social subsystem" [8].

As a result of the aforementioned advances in social justice, a debate about the health realities in CA emerged. Supported by the integrationist ideology of SISCA, the Council of Ministers of Health of Central America (from Spanish Consejo de Ministros de Salud de Centroamérica– COMISCA) was created, with the objective of identifying and prioritizing regional health problems. The creation of COMISCA conveys the intention of the states to discuss realities that were once omitted or worked on individually in each nation, but now seen under a collective scope. Certainly, the emergence of such an organ, attached to SICA, represents for the region and, significantly, for the Central American citizens, the perspective for the development of the Central American health law. It is noted that health is understood under an expanded concept, since these countries have inserted respect for the pluricultural particularities of the CA region into their internal regional arrangements. That is, health encompasses, beyond the understanding of the pathological profile, with respect to the treatment of systemic-organic diseases, the understanding of other social factors, such as: housing, education, leisure and decent wage employment.

The extraordinary meeting of the Heads of State, held in San Salvador in July 2010, highlighted the concern of SICA member countries to adopt measures and mechanisms with the potential to improve the region's current legal, economic, and health frameworks in pursuit of the greater comprehensive well-being of citizens. In the field of ‘Social Integration’, actions were envisioned to prevent health risks and injuries and promote healthy-giving habits in the individual and collective spheres, with the aim of improving salubrious profiles, while acknowledging that each health system cope with different challenges that result from State's action on the organization and regulation of the public and private sectors. Seemingly, this meeting brought up contemporary issues of CA health law, that is, the claim of the struggle for the institutionalization of the right to health in these nations, emphasizing the following five pillars: 1) democratic security; 2) prevention and mitigation of natural disasters and climate change effects; 3) social integration; 4) economic integration and 5) strengthening of regional identity. According to Segura [6:9], the countries that make up SICA face common challenges and opportunities, and in this sense: must adopt measures to strengthen the coincidences that unite them, with a view to designing a path of meetings and political negotiations that allow overcoming the challenges and, a greater use of opportunities to act as a regional bloc. The above, on a vision that must be strengthened and constituted on a series of shared principles, values, and objectives.

To all appearances, the increase in the aging population raises the concern of nations, in altercation between the public and private health sectors, since the financial tensions and new challenges in the qualification of human resources to deal with the dynamic and heterogeneous characteristics of aging are exacerbated. On the other hand, the idea of a more humanized health care and the adoption of mechanisms that allow taking care of the pathological profile of older adults, in the CA context, are the current challenges for the health systems of the region and especially for COMISCA, in its role as the governing body that guarantees regional health.

Part II: Health as a fundamental right of older adults in central America

The health of older adults can be understood as the product of the process of multidimensional relationships and, in such a case, it is understood that its conception should be undimmed, precisely because of the complexity of the term and the heterogeneous characteristics of aging. It is measured by the degree of independence and autonomy, not merely by the absence of disease or advanced age, being often misinterpreted, and even justified, by certain pathological causes of senescence and senility.

As indicated earlier, the mere understanding of health adopted by the WHO does not consider the specifics of the aged group. To this, Moraes and Lanna [10] comment that "health in old age should be a measure of the individual's ability to realize aspirations and the satisfaction of needs, regardless of age or the presence of disease." In other words, "a person is considered healthy to the extent that he or she is able to perform his or her activities alone, fully, even if he or she is very old or has diseases" [11].

In December 2014, the most recent attempt by COMISCA to meet the demands and strengthen health actions in the region was made through the approval of the ‘SICA's Regional Health Policy 2015-2022’ (from Spanish Política Regional de Salud del SICA 2015-2022) at the 44th Ordinary Meeting of Heads of State and Government of SICA. It is to be noted that the region took more than twenty years, after the creation of COMISCA, to establish a regional policy that would analyze and address in an articulated manner, the main health needs of the countries, seen through the lens of Public Health with an equitable and humanized approach.

The SICA's Regional Health Policy 2015-2022 strikes to guide and promote the development of health action and regional integration, to strengthen national and regional jurisdiction processes with an intersectoral approach and a public health focus, to improve the health of populations and their ability to achieve maximum well-being in health [12]. Withal, while recognizing that the CA territory has advanced in the construction of normative frameworks to accommodate social needs, the pronouncement of health as a universal right is a task still in a state of flux, where advances and setbacks in terms of access to health services and availability of medicines come to light. In line with the specific objectives of the policy, the goal is to reach a consolidated regional welfare state under a governance framework that prioritizes the countries' collective interests for optimal regional health management.

The SICA's Regional Health Policy 2015-2022 proposes actions oriented in "complementarity" (its complementary action is more political and strategic than technical and administrative); in "non- substitution" (welcoming the national accountability of countries to meet their health demands, as it is expected that they are self- sufficient and effective in solving public health impasses, moreover, exceptionally considering intervention for emergency cases) in the "non-duplicity" (indicating that the policy is not the only instrument that promotes regional health development, since adherence to international instruments is also admitted); in the "intersectorial approach to health" (the policy warns about the transversality of health in the political, economic and social spheres) and, finally, in the "sustainability of the National and Regional Health Action". Overall, five doctrinal principles are identified, which underlie the creation of SICA's Regional Health Policy 2015-2022, these being: universality; quality; integration and intersectorality; health as a human right and social inclusion and gender equity in health [12].

Legal-health framework for older adults in central America

The interest in promoting respect for the fundamental rights of older person sought not to be taken as a contemporary issue in Latin American countries, since it idealizes a critique of the socio- political contexts of the past. In truth, the up-to-date geronto-sanitary framework of the CA countries is influenced by the international instruments signed by these countries. The chronological order in which these instruments took dialogical space is of great importance when projecting an analysis of the legal-sanitary progress of the health of the CA older adults, since it includes the study of the social contexts from the 70's to the ongoing day. In 1991, the General Assembly of the United Nations introduced the "United Nations Principles in Favor of Older Persons", emphasizing the inclusion of older adults in the community and in the national society. According to the United Nations Organization, at that time it was recommended that member states made the five guiding principles known and important in their internal legislation: I-Independence: considers the right to health in its fundamental condition and the expanded concept of health; II-Participation: emphasizes the insertion of the elderly in their social environment and guides social policies to consider the presence of the elderly in the community nucleus; III-Care: points to comprehensive and universal care, resulting from the maintenance of the principle of independence, in the spheres of prevention, promotion, cure, palliative care, and rehabilitation. The applicability of these criteria is extended to the public and private sectors, without distinction; IV-Self-Realization: deals with the state of full satisfaction, on the pillars of education, culture, spirituality, and leisure; V-Dignity: punishes any form of discrimination in all aspects that influence the integrity of the elderly and their families [13]. The UN's 1992 Proclamation on Ageing posed new challenges and, concomitantly, new future prospects in the global scope of geronto-sanitary law. The UN position can be summarized in two main points: it emphasized the compulsory application of the International Plan of Action on Ageing and then highlighted the support for national initiatives on ageing in the context of national cultures and conditions [14]. And, at this stage, member countries were expected to adhere to and rapidly apply such a positivist social pronouncement, in the search for the common well-being of older persons in the world panorama. As a result of the multiple efforts made by Latin American countries in the last two decades, the health of older adults has gained prominence in the national and international health-legal framework in North, South, and CA. Given the case of the CA region, the debates are raised, by choice, in the regional agenda of the COMISCA, where information regarding the health status of the people is presented and discussed, fitting the demands/needs of the aging segment. In 2012 in particular, there was a historic success at the Latin American level. The 3rd Regional Intergovernmental Conference on Ageing in Latin America and the Caribbean was held that year in the capital of the Republic of Costa Rica, San José, organized by ECLAC and the Costa Rican Government. On that occasion, the member countries recognized that access to justice is an essential human right and a fundamental instrument to ensure that older people can exercise and effectively defend their rights [15]. With specific regard to the health of older adults, it was agreed to promote the universalization of the right to health and the design and implementation of comprehensive preventive health care policies. The SICA Member States have enacted a series of laws aimed at protecting and maintaining the integrity of older adults in their internal regulations. These laws have served as an impetus to promote intersectoral dialogue between state and non-state institutions (public and private) in an attempt to encourage reflection on the various determinants that influence the health of older adults (Table 2). Some countries express in their Federal Constitution, recognition of individual and collective rights of the aging population. It is also noted that most countries consider the age of 60 to define the onset of old-age, with the Republic of Costa Rica diverging by stipulating the age of 65. In Guatemala, for example, Art. º 51 of the Political Constitution places the responsibility of the State to protect the physical, mental and moral health of older adults, guaranteeing the right to food, health, education, security and social security [16]. Art. º 77 of Nicaragua's Major Law recognizes that older adults are entitled to protective measures from the family, society, and the State [17]. Art. º 56 of the Panamanian Political Constitution grants the elderly the immediate right, in the individual and collective sphere, to physical, mental and moral health protection and a guarantee of healthy food, education, security and welfare [18]. Already the Honduran constitutional text, in its Art. º 117 <ratified in 2005>, exposes special protection to the elderly under the responsibility of the State [19]. Contrary to the aforementioned cases, the Republics of Costa Rica and Belize do not expressly consider rights for older adults.

| Nation | Title | Details | Promulgation date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belize | * | * | * |

| Costa Rica | Comprehensive Law for Older Adults (from Spanish Ley Integral para la Persona Adulta Mayor, n. º 7935) | Older adults are guaranteed equal opportunities and a life of dignity in all spheres; social participation and the permanence of the elderly within their families and communities (whenever possible); comprehensive and inter-institutional care, and social protection and security (Art. º 1, Inc. a - f). Older people are those who are 65 years of age or older (Art. º 2). Older adults have the right to education; leisure; housing; public and/or private financial credit opportunities; primary, secondary, and tertiary care; social security; social assistance; participation in the country's productive processes; legal and psychosocial protection; and differentiated treatment in public and private entities (Art. º 3, Inc. a - l). The right to employment without discrimination of any kind and the enjoyment of the same labor rights as other population segments (Art. º 4, Inc. a-c). The integrality of the older adults includes the protection of his/her image, autonomy, thought, dignity and values (Art. º 6). The rights mentioned in this law are of non-transferable quality, with the sole exception of the transfer of the financial benefit by pension (Art. º 9). It is the state's duty to guarantee optimal conditions of health, nutrition, housing, comprehensive development and social security for older persons (Art. º 12). Older adults shall receive differentiated treatment in all public and/or private institutions, and these in turn must maintain adequate and comfortable infrastructure for the use of older adults (Art. º 13). The State must provide comprehensive attention to health needs in the individual and collective spheres (Art. º 17). The financing of programs and services aimed at the aging population will be supported by the public and private sectors (Art. º 51) [20]. | November, 2001 |

| El Salvador | Comprehensive Law for Care of Older Adults (from Spanish, Ley de Atención Integral para la Persona Adulta Mayor, n. º 717). | An older person is considered to be one who is 60 years of age or older (Art. º 2). The care of older adults is the total responsibility of the family when older adults do not have the means to do so (Art. º 3) and they receive assistance from the State in case of inability to perform this task (Art. º 4). The following rights are dictated under a fundamentalist category: to non-discrimination for any reason whatsoever; to proper attention for the enjoyment and exercise of their rights; to food, transportation, and housing; to medical, geriatric, and gerontological assistance; to good treatment and solidarity from the family and the State; to free cultural and leisure programs; to employment; to protection against abuse and mistreatment; to active listening; to freedom; to social security; to information; to active aging, and to the complementary enjoyment of the other rights recognized in the Constitution (Art. º 5, Inc. 1-15). Comprehensive attention is understood as the set of governmental and non-governmental actions, coordinated by different state and private bodies, of geronto-sanitary interest (Art. º 7, Inc 1-12). The financing of the actions proposed in this law will occur on public and private, national or international resources (Art. º 9). The rights set out in the law are not transferable (Art. º 28) [21]. | February, 2002 |

| Guatemala | Law for the Protection of Older Adults (from Spanish, Ley de Protección para Personas de la Tercera Edad, n. º 80). | The State guarantees and promotes the right of older adults to an adequate standard of living in conditions that offer them education, food, housing, comprehensive geriatric-gerontological assistance, leisure and social services necessary for a useful and dignified existence (Art. º 1). Older people are all people of any race or skin color who are 60 or older (Art. º 3). The benefits set out in the law apply to all elderly persons in Guatemalan territory (Art. º 4). The social participation of older adults should be respected in the country's development processes (Art. º 5). In order for older adults to enjoy these rights, they must first register with departmental agencies (Art. º 7). Families are obliged to assist and protect older adults (Art. º 9). Health and medical care at all levels of care is a fundamental right of all older people (Art. º 13). The State undertakes to promote nutritional, oral and mental health education, free of charge for older adults (Art. º 16), together with healthy eating that takes into account the issues of old-age (Art. º 17). Formal or informal education is a right for all Guatemalan older people (Art. º 20). The state guarantees an economic entry, through access to employment, without any kind of discrimination (Art. º 22). Older adults are entitled to a special discount on basic public services. Older adults are entitled to differentiated treatment by public and private institutions throughout the national territory (Art. º 30, Inc. a-e) [22]. | 1996 |

| Honduras | Integral Law for the Protection of Senior Citizens and Retirees (from Spanish, Ley Integral de Protección al Adulto Mayor y Jubilados, n. º 199). | A person who has reached the age of 60 or more is an older person (Art. º 2). The applicability of this law is based on the principles of autonomy and self-realization, participation, equity, co-responsibility, and preferential care (Art. º 4, Inc. 1-5). The individual rights of older adults are the recognition of old age as a very significant period of human life due to experience and wisdom; access to public services of promotion, prevention, treatment and rehabilitation; dignified work that allows them to achieve a better quality of life; no discrimination and no prejudice of being "sick" due to the fact of being older; respect for privacy and intimacy; education that favors self-care; a work environment and living conditions that do not increase their vulnerability; respect and consideration of their practices, knowledge, and experiences; information on their health status and appropriate treatment that respects their consent to such treatment; not to be institutionalized in nursing homes without prior consent (Art. º 5, Inc 1 – 16). Art. º 6 enacts the creation of the Política Nacional del Adulto Mayor y Jubilados. The family must care for the physical, emotional, and intellectual wholeness of the elderly (Art. º 9). In order to provide comprehensive attention to the health demands of the elderly, the Programa Nacional de Atención Integral al Adulto Mayor is established (Art. º 10) [23]. | May, 2007 |

| Nicaragua | Regulations of the Law for Older Adults (from Spanish, Regulamento de la Ley para el Adulto Mayor, n. º 51). | An older person is defined as an individual aged 60 or over, national or nationalized. Comprehensive care is understood as the assistance that the family, society and the State must provide to the elderly in order to meet their physical, material, biological, emotional, social, legal and family needs (Art. º 2). The National Council for Older Adults, with the participation of the institutions that comprise it, will facilitate the means and conditions necessary for all older people to receive comprehensive care that allows them access to food and nutritional security, medical treatment and medicine, in a safe environment and with respect for the people to whom it legally corresponds, both in the private and state spheres (Art. º 13). Older adults have the right to health in a series of intersectoral actions (Art. º 14, Inc. a-e). Older adults have the right to social security and retirement under a social security system (Art. º 19). Older adults have the right to basic, middle and higher education (Art. º 25) and literacy programs for older persons (Art. º 40). Leisure (Art. º 26); culture (Art. º 27); sports (Article 28) and housing (Art. º 29) are rights guaranteed by the State, through intersectorial actions between public and private institutions. The activities aimed at the aging population will be financed by the public budget and with private help (Art. º 50), and national or international contributions may be considered for these purposes (Art. º 52) [24]. | August, 2010 |

| Panama | Law for the Comprehensive Protection of the Rights of Older Adults (from Spanish, Ley para la Protección Integral de los Derechos de la Persona Adulta Mayor, n. º 36). | Older people are considered to be citizens aged 60 or over (Art. º 1). The right to freedom is recognized (Art. º 4, Inc. 1 - 3); to social participation (Art. º 5); to remain within the family nucleus when possible and to be institutionalized in homes when impossible (Art. º 6); to live a dignified and independent life (Art. º 7); to leisure (Art. º 8; Art. º 12); to sports (Art. º 13); to health (Art. º 16); to employment (Art. º 17). The financing of the actions aimed at Panamanian older adults will be planned in the annual budget plan (Art. º 39) [25]. | August, 2016 |

Note: *Did not show any registries.

Table 2: Description of the constitutional articles that address the rights of older adults in CA, according to the National Laws.

The national laws for older adults in CA countries are inserted into an environment of social protection consistent with international recommendations on human and fundamental rights of every individual, with an emphatic focus on health, education, housing and social security/retirement. One can see that, among these social rights, the community participation of older adults is privileged in order to create a sense of belonging and citizen empowerment in the construction of fair, inclusive, and equitable societies that do not ignore the voice of the aging population segment [20-25].

Central American national laws for older adults

It becomes relevant, at first, to mention health policies and see which characteristics differentiate them from other policies, also of a social nature. It is equally important to reiterate that health is a fundamental social right, belonging to the second generation/ dimension rights and involving higher costs than those of the first generation. In turn, social rights are implemented through public policies, under the responsibility of the Executive and Legislative branches [26], aimed at achieving objectives in the individual and collective spheres. Adding, Cohn [27] comments that: It is necessary, therefore, to take into account that when dealing with health policies, what becomes the focus of the study is the State's decision-making process (that is, those groups that hold power in that historical conjuncture being studied, and constituting the governments), in the face of a series of possibilities of alternative choices, each of which represents gains and losses for different social groups, taking, however, as a reference that the State is always responsible for guiding its decisions for the common good of society. In turn, health policies are categorized as social policies. Fleury and Ouverney [28-34] define social policy as "permanent or temporary actions related to the development, reproduction, and transformation of social protection systems. They further comment that social policies comprise relationships, processes, activities, and instruments that aim to develop public responsibilities (state or otherwise) in promoting social security and collective well- being. This is why the authors assert that social policies have a multifaceted dynamic, including interventionist actions in the form of distribution of resources and opportunities, the promotion of equality and citizenship rights, and the affirmation of human values. Health policies aimed at the aging population, known as "policies for older adults" or "policies for the third-age", focus on actions organized by the State, which aim to meet/respond to the difficulties/needs expressed by older persons, whether social, political, health, economic, cultural or environmental. Therefore, it is argued that national policies for older adults express the State's philosophy on the dilemmas and issues that bind it to senior citizens, in an immediately positivist principle of social responsibility.

According to Marín [29], the formulation of policies aimed at the aging population should consider the relationship with other age groups and their ability to generate benefits not only for older persons, because the welfare of the older population is based on the living conditions of the young years, hence the statement that geronto-sanitary programs also serve young people, with special consideration in those who suffer from some kind of disability. The author mentions a sequence of justifications for the development of this type of policy, among which are the following: Aging must be considered as a medical care challenge; countries will age, even if they are economically developed; aging is heterogeneous and markedly female; it is recommended to homologate the services or care provided in a long-term institution and design an adequate financing system; today there is a shortage of medical professionals specializing in the field of health care for the elderly in view of the number of elderly people in societies and, in this sense, the elderly suffer discrimination when they are not offered the necessary geriatric-geriatric medical services [29].

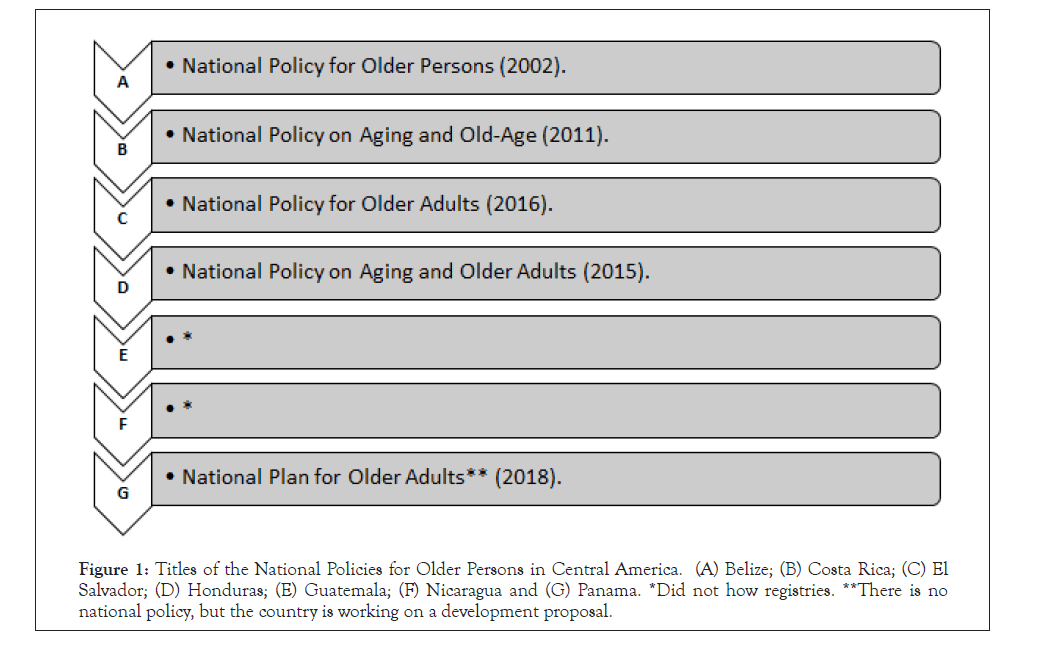

Acknowledging that the current challenges are many, CA countries have materialized their geronto-sanitary apprehension through the following National Policies on Aging (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Titles of the National Policies for Older Persons in Central America. (A) Belize; (B) Costa Rica; (C) El Salvador; (D) Honduras; (E) Guatemala; (F) Nicaragua and (G) Panama. *Did not how registries. **There is no national policy, but the country is working on a development proposal.

Belize's National Policy on Aging (hereafter NPA) comprises nine axes of intervention, as follows: 1) national mechanism (establishing the creation of the National Council on Aging); 2) education and media (aiming at providing access to education and making the population aware of aging); 3) health and nutrition (facilitating access to health services through the holistic perspective, considering the concept of health recommended by the WHO); 4) social security (providing independence rather than dependence, preventing crises as much as possible); 5) secure income (emphasizing the social participation of older adults, specifically economic participation); 6) family (making the family nucleus responsible for assisting the elder, whenever possible); 7) housing and healthy environment (adequate and accessible housing for the elderly); 8) legal (proper legal compliance with the framework of the law) and 9) research (updating the social and health indices that concern the elderly) [30]. It is worth mentioning that no other policy was found that has updated the NPA of 2002.

In the case of the Costa Rican NPA, the main objective is to strengthen the State's responsibility to ensure the comprehensive protection of the elderly, in all areas provided by specific law (Costa Rica, 2011). Costa Rica's NPA is structured along five strategic lines, such as: 1) social protection, income and poverty prevention (working specifically on social inequities and promoting the social well-being of the elderly); 2) abandonment, abuse and mistreatment of the elderly (monitoring, through prevention and punishment programs, all forms of physical, moral and/or psychological aggression); 3) social participation and intergenerational integration (strengthening of spaces and mechanisms for social control that include the participation of older persons); 4) consolidation of rights (dissemination and development of information for the validation of the rights contemplated in specific law) and 5) comprehensive health (universal guaranteed access to the Social Security System in Health and access to comprehensive care in health services) [31].

On the other hand, the Salvadoran NPA aims at protection, respect, family and community participation, access to public services and improvement of the quality of life of the elderly (El Salvador, 2016). Thusly, El Salvador's NPA contemplates ten strategic axes, being: 1) empowerment, participation and enjoyment of rights (promoting citizen participation of older adults and ensuring social inclusion based on respect and dignity); 2) protection and access to justice (punishing any and all forms of violence or form of vulnerability of the social rights of older adults); 3) comprehensive health and care (boosting the supply of health and nutrition services through the timely reception older adults); 4) social services (implementing social services for the promotion of autonomy, independence and permanence of the elderly in their common surroundings); 6) education (improving knowledge management on aging and access to education); 7) physical activity, sport and culture (fostering these three activities); 8) economic entry and access to benefits (seeking better economic opportunities for older persons); 9) housing and accessibility (improving universal access to housing and habitat); 10) attention to specific groups (attention to minority groups such as: LGBTI+; people deprived of freedom; indigenous peoples; older people with disabilities, strengthening the rights and services of older people facing multiple discrimination) [32].

The main objective of the Honduran NPA is to "generate health, socio-political, legal, environmental, economic, cultural and scientific conditions, with a focus on rights that facilitate the comprehensive development of active and healthy aging" [33]. In turn, the Honduras' NPA has nine strategic lines, being respectively: 1) adaptation of the current health model to the specific needs of the aging and old age process; 2) promotion of the offer of friendly, interactive and receptive spaces that contribute to the active and healthy aging of older persons; 3) awareness and communication about active aging and old age; 4) efficient management of public spending on attention to the dynamics of aging and old-age; 5) integration of the legal framework under a social protectionist and comprehensive approach to older adults; 6) promotion of the participation of older adults in the various cultural expressions of the country; 7) establishment of mechanisms to generate economic income for older persons who are not affiliated to the social contribution regime; 8) satisfaction of the basic conditions of social development and 9) generation of evidence for decision making, related to the demographic transition and old-age [33]. In the case of Guatemala and Nicaragua, it was not possible to find a NPA or proposal plan. We consulted the official websites of the Consejo Nacional del Adulto Mayor-CONAM (for Nicaragua) and the Comité Nacional de Protección a la Vejez-CONAPROV (for Guatemala). The case of Panama, which also has no NPA, draws attention; however, the country has been working since 2014 on the development of the National Proposal for Older Adults, to subsequently achieve the enactment of Panama's own NPA. According to the official website of the Ministry for Social Advancement, the Panamanian NPA would have as its main objective "to promote and guarantee the quality of life of the elderly, through the comprehensive satisfaction of their needs, their active participation and promotion of civil and social rights, through articulated responses from the State and the community, favoring their insertion as citizens" [34]. Finally, the analysis of the CA NPAs, allowed us to identify that there are some similar doctrinal principles (Table 3).

| Belize | Costa Rica | El Salvador | Honduras |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuality | Universality | Focus on Rights | Autonomy |

| Independence | Equity | Autonomy | Self-sufficiency |

| Choice | Dignity | Independence | Preferential assistance |

| Accessibility | Intergenerational Solidarity | Gender Equity | Dignity |

| Role Changes | Social Engagement | Dignity and Respect | Active Aging |

| Family Care | Social co-responsability | Intersectoriality | Co-responsibility |

| Dignity | Social Inclusion | Social Engagement | |

| Freedom of Religion | Interinstitutionality | Intergenerational Solidarity | |

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 3: Doctrinal principles found among the NPA in CA countries.

Human dignity consists of values that respect the guarantee of rights that the state recognizes for the individual. In the case of the CA NPAs, these principles explain the Government interventions of these countries in the recognition and defense of the dignity of the older person, not only for the fact of being aged, but for the fact of being, per se, an individual who is entitled to the highest rights, and with regard to equity, it reflects the countries' attempt to provide the services and means necessary to maintain the dignity and integrity of their aged citizens, prioritizing care interventions that promote autonomy and independence.

Debating the issue of the health of older persons is, in fact, a complex and challenging task. It appeals beyond an academic preparation and/or interprofessional and multidisciplinary experience, a multifaceted look, often difficult to conceive when one has as ideology of uniprofessional and/or unidisciplinary training. More precisely, the very concept of the health of older persons is configured as a locution due to this understanding. As voiced by Marín [29], there is no logic, within the geronto-sanitary dimension, in proposing public policies to meet the demands of human aging if one does not incorporate, within all stages of policy design, the number of professionals with training/qualification in the area of health of older adults.

Such affirmation would permeate a scenario mediated by the validation of rights, however, with the fear of human resources limited to the old and to professional hegemony, leading doors to assistance discrimination. Discussing the training of these professionals, it is vital to work on geriatric-gerontological skills to understand the various heterogeneous aspects of human aging and its current challenges; to differentiate the pathophysiological changes associated with aging; to deepen the thematic study of social psychological aging to, finally, are able to perceive older adults as biopsychosocial and functional beings.

As for COMISCA, this work found out that the council has not yet incorporated in a detailed way the issue of population aging through the management of the geriatric-gerontological clinic, as proposed by Moraes [11]. Although the responsibilities of the organ are many and complex, until now there is no evidence of a tangible regional intervention on CA aging. In this statement, an element to consider is the divergence of the health profile of the countries under its tutelage. On the one hand, the Republics of Costa Rica and Panama have, respectively, the best health rates in the region, in almost all aspects recommended by ECLAC. Other countries such as Belize, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador are struggling to keep up with regional development.

The enactment of SICA's Regional Health Policy 2015-2022 was regional thinking materialized by CA teamwork and bravery. It was the target of failed interventions, accelerated propositions and weak planning in its first conception. Notwithstanding, these initial experiences opened the field for the use of resources and the materialization of a pluri-annual plan, making possible the internationalization of a common health instrument. Howbeit, the mere acts of formulating, approving and pronouncing laws on human aging and on the special needs of the older population do not translate into the real enjoyment of these rights. It is necessary for society as a whole, and this strongly includes older persons as a primary target, to incorporate adherence and respect for such norms into their daily lives.

Eventually, to cognize in a futuristic way a regional policy aimed at meeting the spontaneous and chronic demands of human aging may not be a despairing or unreasonable undertaking. In fact, CA countries have all the organizational and integrationist forms for such a proposition. What is missing, however, is the recognition of the potentialities of each nation, and the confrontation of the contemporary challenges of population aging in an articulated manner. It would be a palliative process, where the handouts of each nation would come to totalize efforts in the pursuit of this regional dream, allowing bestowment for all nations equitably, however, recognizing the socio-sanitary realities of each nation.

In this study it was possible to discern that, in addition to the current internal regulations aimed at promoting comprehensive care for aging populations in CA, the health actions for the older persons find strong state support, backed by single texts in the political constitutions in some CA territories. Notwithstanding, it was noticed the absence of constitutional articles defending the rights of older adults in the constitutions of Costa Rica and Belize, for example, and more deeply, identified the scarcity of a national law that provides legal defense of the rights of older adults in Belizean territory. By way of clarification, it can be seen that the non-insertion of constitutional texts oriented to attend the demands of older adults did not mean that the Republic of Costa Rica was not interested in promoting and defending the wholeness of its older citizens. It is felt that the sympathy for the improvement of the quality of life of older people has gained prominence through the new integrationist processes that arose in the 90's, which said about social, economic, cultural, health issues and CA identity in a constructivist perspective.

Conclusion

The presence of COMISCA, a regional body officially recognized by the CA countries and mediator of the health debate, represents for the region an opportunity for socio-sanitary development and the strengthening of the health systems of these countries, based on the positivist aspects of health law. The CA States agree that their societies are in a process of constant structural change, not only because of the aging population, but also because of the changes intentionally outlined in the regional integration proposals. And in this environment, it cannot be avoided that older persons must be seen through the lens of intersectoriality, but in order to achieve this, it is first necessary to produce changes in the hegemonic training of the various professionals who produce health care acts and, emphatically, in the management of the health sector in the public and private spheres. To conclude, the efforts of CA countries are highlighted, in the aspiration to expand comprehensive health protection for older adults and develop intersectoral competencies to promote the enhancement of the capabilities, their autonomy and social insertion. Perhaps the greatest geronto-sanitary challenge of the CA region, in a broad view, is to actually achieve the materialization and institutionalization of fundamental rights. This is a shared task, which does not simply involve the State; it also needs the help of society and the empowerment of older citizens, aiming for the full recognition and enjoyment of such rights.

REFERENCES

- Santos ZMSA, Frota MA, Martins ABT. Health technologies from theoretical approach to construction and application in the care setting. 2016.

- Serge M. The concept of health. Rep Public Health. 1997;31(5): 538-542.

- Melo EA, Mendoça MHM, Oliveira JR, Andrade GCL. Changes in the National Care Policy: between setbacks and challenges. Saúde Debate. 2018;42(1): 38-51.

- Fontelles MJ, Simões MG, Farias SH, Fontelles RGS. Scientific research methodology: guidelines for writing a research protocol. Rev Pan Medicine. 2009;32(1): 25-34.

- Andrade FB, Ferreira-Filha MO, Dias MD, Silva AO, Costa ICC, Lima EAR, et al. Promoting elderly mental health in basic care: community therapy contributions. Texto Contexto Enfermagem. 2010;19(1): 129-136.

- Segura R. Central American Integration System: coincidences, challenges and opportunities in the framework of its governance, governability and effective management of its resources. 2018.

- Central American Integration System. Protocol of Tegucigalpa, Honduras, 1991.

- Central American Integration System. Treaty for the Social Integration of Central America, San Salvador, 1995.

- Sposati A, Lobo E. Social control over policies. Rep Public Health. 1992;8(4): 366-378.

- Moraes EN, Lanna FM. Multidimensional evaluation of Older Adults. 2014.

- Moraes EN. Pan American Health Organization Brazil; Ministry of Health. Older adults’ health care: conceptual aspects, Brasilia – DF. 2012.

- Council of Ministers of Health of Central America. SICA Regional Health Policy. 2016.

- United Nations Organization. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The United Nations Principles for Older Persons. 1991.

- United Nations Organization. Proclamation on Aging. 1992.

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Charter of San José on the Rights of the Elderly in Latin America and the Caribbean. Third Regional Intergovernmental Conference on Aging, San José. 2012.

- Guatemala. Political Constitution of the Republic of Guatemala. Political Agreement No. 18. 1993.

- Nicaragua. Political Constitution of the Republic of Nicaragua. 1995.

- Panama. Political Constitution of the Republic of Panama. 1972.

- Honduras. Political Constitution of the Republic of Honduras. 1982.

- Costa Rica. Legislative Assembly. Costa Rican Legal Information System. 2001.

- El Salvador. Comprehensive Law for the Care of Older Adults. 2002.

- Guatemala. Congress of the Republic. Law for the protection of Older Adults. 1996.

- Honduras. Comprehensive law for the protection of senior citizens and retirees. 2007.

- Nicaragua. Regulation of the Law for Older Adults, no. 51. 2010.

- Panama. Law for the Comprehensive Protection of the Rights of Older Adults. 2016.

- Bueno JA. Health a basic social right. 2014.

- Cohn A. The study of health policies: implications and facts. 2012.

- Fleury S, Ouverney AM. Health policy: a social policy. 2012.

- Marín PPL. Reflections to consider in a public health policy for older adults. Rev. Med. Chile. 2007;135(1):392-398.

- Belize. National Council on Ageing. National Policy for Older Persons. 2002.

- Costa Rica. National Council for Older Adults. National Policy on Aging and Old-Age 2011 - 2021, San José. 2011.

- El Salvador. National Council of Comprehensive Attention to Older Adults. National Policy for Older Adults, San Salvador. 2016.

- Honduras. Secretariat of Development and Social Inclusion. National Policy on Aging and Older Adults, Tegucigalpa. 2015.

- Panama. MINDES launches national plan for older adults. 2018.

Citation: Gutiérrez-Murillo RS (2021) Health and Social Rights of Older Adults in Continental Central America: A Comparative Historical and Legal Analysis. J Aging Sci. S9: 003.

Copyright: © 2021 Gutiérrez-Murillo RS. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.