Indexed In

- Academic Journals Database

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- JournalTOCs

- China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI)

- Scimago

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- MIAR

- University Grants Commission

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2021) Volume 12, Issue 3

Evaluating Child Malnutrition in Southern Belize using an Anthropologic Screening Tool

Sara Brenner* and Raymond BaliseReceived: 30-Apr-2021 Published: 21-May-2021, DOI: 10.35248/2157-7560.21.12.453

Abstract

The WHO describes the double burdenal of malnutrition as obesity coexisting with under nutrition. These conditionals increasing prevalence makes it an important disorder to monitor and address. Screening tools exist to evaluate child malnutrition in hospital settings, but few are available to evaluate children elsewhere. This study taught Community Health Workers (CHWs) in Southern Belize to implement the Hasegawa et. al. screening tool for child malnutrition. Data was collected at home visits, mobile clinics and at two rural polyclinics. Descriptive statistics were performed, and the data was analyzed using two tailed t-tests and the Anscombe-Glynn test for kurtosis. 171 child-mother pairs were screened. Of the children screened, 10 met the WHO definition of underweight, 29 met the WHO definition of overweight, and 30 met the WHO definition of stunted. The combination of measured weight and length, expressed as the weight for length z-score, showed a statistically significant increase of 0.83 [95% CL: 0.51 to 1.14, p<0.0001] with 4% (6/167) of the children showing clinically significant wasting and 17% (29/167) being clinically overweight. The screening tool correctly identified all 10 underweight children. Further modelling is needed to develop an anthropological measure to assess the double burden of malnutrition.Keywords

Child malnutrition; Community health worker; Double burden of malnutrition

Abbrevations

CHW: Community Health Worker; MOH: Ministry of Health

Introduction

Child malnutrition is prevalent, worldwide affecting more than 149 million children under 5 [1]. The issue of child malnutrition has become increasingly complex with the increased prevalence of obesity. Malnutrition can be defined as stunted growth, overweight growth, wasting or a combination of these due to poor nutritional intake [1]. Children who suffer from any form of malnutrition are at risk for irreversible harm including stunted brain development, increased risk for infections, decreased productivity in adulthood, and early death [1-5]. It is estimated that there are 2.1 million stunted children under 5, and 1.1 million overweight children under 5 in Central America [1]. This ‘double burden’ of malnutrition is described by the WHO as undernutrition coexisting with obesity [4]. The changing dynamic of this condition makes it an especially important disorder to monitor and intervene. In order to prevent the long-term effects of child malnutrition it is vital to intervene early in a child’s life. The first 1000 days of a child’s life are sometimes referred to as the ‘window of opportunity’ for a child, as it is the most vital time to prevent long term stunting due to malnutrition [2].

Many screening tools currently exist to detect child malnutrition in the hospital setting, but to our knowledge, the screening tool developed by Hasegawa et al. is the only tool developed to be utilized in the community setting, administered by community health workers [2]. In order to catch children within the ‘window of opportunity’, action in the community setting is a necessity. The Hasegawa et al. screening tool could give CHWs the opportunity to catch children at risk of malnutrition early in their life, before irreversible damage has occurred. However, further studies are needed to confirm the feasibility and efficacy of such screening questionnaires.

The Belize Ministry of Health has identified the Southern districts as having the worst indicators for child malnutrition in Belize [5]. The Ministry has identified preventing or treating child malnutrition in the first two years of life as a goal for their Health Sector Strategic Plan 2014-2024 [5]. This study documents the strengths and limitations of the Hasegawa et al. screening tool in rural Belize both in the setting of the CHW and in polyclinics throughout the Independence catchment area and provides evidence for the double burden of malnutrition.

Materials and Methods

Study area: Stann creek and toledo districts

The Stann Creek and Toledo districts of Belize are the two southern most districts in the country. An estimated 45%-100% of households in the sample area earn less than 20% of the national income [6]. Furthermore, according to the Abstracts of Statistics Belize in 2018 the district of Toledo had by far the highest infant mortality rate in the country of 29.5 [7]. The district of Stann Creek also had a significant infant mortality rate of 20.7 [7]. In 2000, 39.8% of the rural Stann Creek population identified as Mestizo, 22.1% as Creole, and 17.6% as Mayan and 74.7% of the rural Toledo population identified as Mayan [8]. This area is extremely heterogeneous and numerous languages are spoken in even one community.

It cannot be understated how different these cultures are in nearly every aspect. The ethnic identity of a family or community dictates everything from family structure to diet. Most of these factors are well established social determinants of health. Furthermore, the rural villages in each region remain rather homogenous in their ethnic breakdown. For example, in the rural village of Cow Pen, the major ethnicity is Mestizo. Because of this, the cultural and socioeconomic effects of each ethnicity are persistent within a community. The demographics of the study population are visible in Table 1.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex assigned at birth | ||

| Female | 79 | 46% |

| Male | 92 | 54% |

| Location sample collected | ||

| Bella Vista | 47 | 27% |

| Red Bank | 74 | 43% |

| Cow Pen | 3 | 2% |

| Trio | 7 | 4% |

| Independence | 40 | 24% |

| Age | ||

| 6 months and younger | 76 | 44% |

| 7-12 months | 40 | 24% |

| 12-24 months | 55 | 32% |

Table 1: Demographics and sample location.

Study period, sampling and measurements

A cross-sectional study assessing children aged 0-24 months old for malnutrition and stunting was conducted between May and July of 2019. This study took place on the southern border of the Stann Creek district and the Northern border of the Toledo district which includes the Independence catchment area outlined by the Belize Ministry of Health. Rural catchment areas execute most of their care through polyclinics, or rural outpatient clinics that provide a wide variety of care. There are two polyclinics in this area: Bella Vista and Independence polyclinics where the majority (48%) of the sampling took place at well-child visits. Other sampling, accounting for 27% of the data, occurred in the rural villages that these polyclinics serve, where CHWs screened child- mother pairs with the researcher. A mobile clinic day was deployed on a single day in the rural village of Red Bank where child-mother pairs were also screened. This accounted for the remaining 25% of the samples.This study was designed using the methods outlined in the Hasegawa et al. study. Sampling was mainly executed via convenience sampling as child-mother pairs attended vaccination appointments at the Polyclinics. However, sampling in the villages through home visits or mobile clinics, gave CHWs the opportunity to utilize the tool so they could begin to incorporate it into their general practice.

Screenings were conducted in semi-structured interview format to collect the anthropologic variables outlined in the Hasegawa et al. screening tool. However, height and weight were measured using either supplies already present in clinics, or foldable rulers and a mobile scale, in order to best approximate the resources CHWs and clinic personnel use on a day-to-day basis. The purpose of using different resources for height and weight measurements was to best reflect the reality the CHWs and clinic personal would experience without the researcher present.

Most interviews were conducted in English or Spanish depending on the mother’s preference by the researcher who spoke English and Spanish. When mothers preferred Qeqchi or other Mayan dialects, CHWs conducted the interviews under the supervision of the researcher. Child health cards were also referred to during interviews to collect the child’s birth weight. Before conducting the interview, the mothers were consented following the guidelines established by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board. Mothers were told that their participation in the study was entirely optional and that their care would not be impacted by their participation in the study.

Anthropologic variables were collected in the same manner outlined in the Hasegawa et al study. In the field, data was collected using paper records. After data was collected in the field, it was transferred to a REDcap data base [9,10] project hosted by the University of Miami secure storage. The REDCap data collection tool allowed the data to then be analyzed in SAS 9.4 (TS1M5) [11] and R 4.0.2 [12] with the tidyverse [13] (version 1.3.0), tidyREDCap [14](version 0.2.0), janitor [15] (version 2.0.1), anthro [16] (version 0.9.3) and moments [17] (version 0.14) packages.

Community health worker education

CHWs in Belize are employed on a voluntary basis. They provide nutritional and health promotion services to the communities in which they live. CHWs can help provide care and referral services in under-resourced settings. Each CHW reports to the Ministry of Health official that is stationed at the Polyclinic serving their area. The Independence catchment area has between 8-10 CHWs with at least one in each village and some larger villages having multiple.During the study period, CHWs gathered at the Independence Polyclinic for a series of trainings. One was conducted by the researcher on the Hasegawa et al. screening tool. Workbooks were provided to CHWs for the purpose of recording the metrics of children in their own community. Growth curves were also provided to the CHWs. During the workshop, training was provided on how to properly plot children on the growth curves using publicly available WHO training material. An open conversation was conducted about many of the variables in the screening tool such as diet, water source, and parental education in order for these variables to be as culturally competent as possible.

After the workshop, the researcher traveled to the villages of Cow Pen and Red Bank to do home visits with the CHWs in these communities. Travel to other rural villages was limited by a lack of transportation.

Statistical analysis

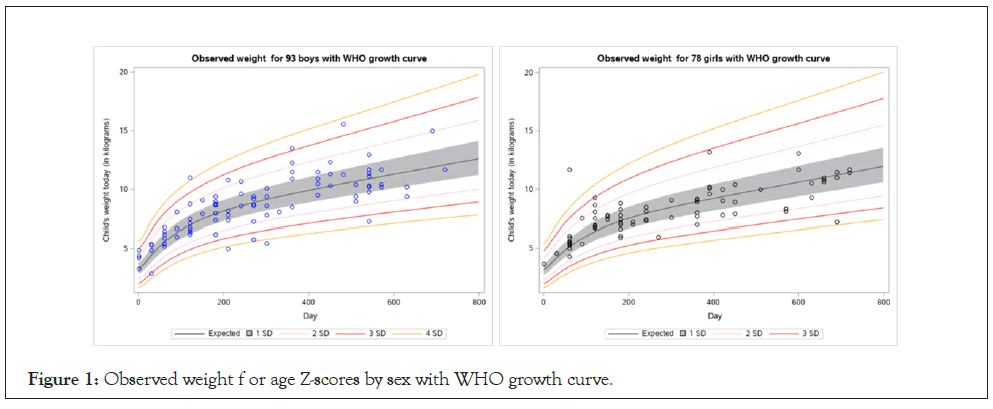

Three metrics of malnutrition were identified prior to gathering data: weight, length, and weight for length. Children were evaluated relative to age and sex specific norms developed by the WHO [18] using algorithms instantiated in the R anthro package. Following the standards proposed by the WHO, a length z-score less than two is indicative of stunting, a weight z-score less than two is considered underweight, a weight for length z-score less than two is considered wasting [19]. Further, prior to analyses, overweight was defined as a weight for length z score greater than two, per WHO guidelines. Weight-for-age Z-scores by sex are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Observed weight f or age Z-scores by sex with WHO growth curve.

After descriptive statistics were performed, the samples were scored in SAS (and R) based on the Hasegawa et al. original model. In their model, points were assigned to specific variables in an attempt to predict nutritional status.Two kinds of tests were used to evaluate the children’s anthropomorphic scores. For each of the three metrics, one sample, two tailed t-tests were used to test for differences relative to an expected z-score of zero. Given our hypothesis that the distributions could contain an excessive number of children the both the high and low extremes of the distributions we also tested for departure from normality using the Anscombe-Glynn test for kurtosis from the R moments package. Given the use of two analyses on three primary endpoints a Bonferroni adjusted p-value of less than 0.008 (i.e., p<0.05/6) was considered statistically significant.

Results

After scoring with the algorithm from the Hasegawa et. al study, 10 children (6%) were predicted to be underweight, 30 children (18%) were predicted to be stunted, 6 (4%) were predicted to be wasting and 29 (17%) to be overweight. Predictive modeling to determine risk factors significant for malnutrition in this population was not possible as there were not enough children meeting the WHO definitions of malnourishment.

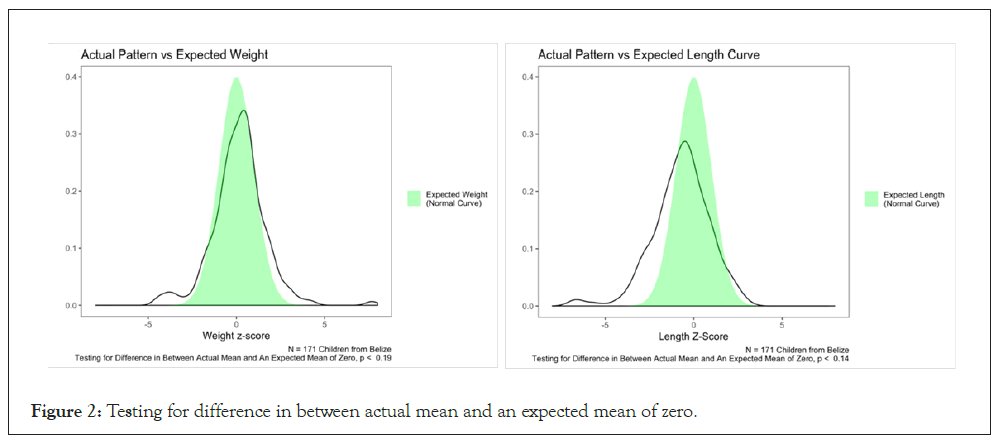

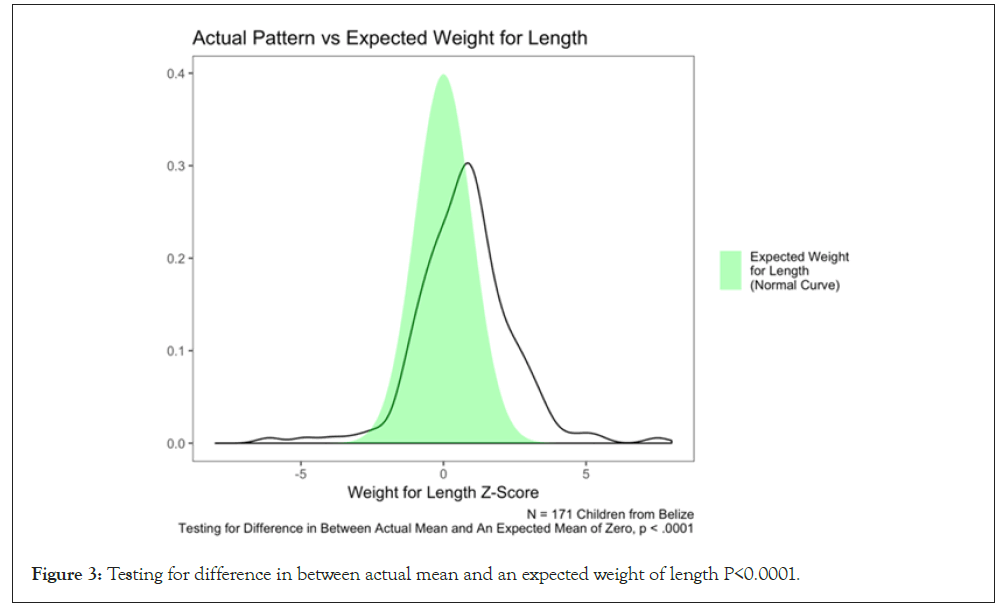

A total of 171 child-mother pairs were screened. Two children could not be assessed for length, three for weight and four for weight for length. As can be seen in Figures 2 and 3, all three distributions showed notable departures from normality with heavy tails (p<.00001). While weights were typically slightly higher than normal [mean z-score=0.15, 95% CL: -0.08 to 0.38] and lengths were on average lower than normal [z=-0.43, 95% CL:-1.02 to 0.15] neither of these effects were statistically significant. However, a large number of children showed clinically significant symptoms of malnutrition. While only 6% of children were underweight (10/158), 18% (30/169) of the children were stunted. The combination of the two factors, expressed as the weight for length z-score showed a statistically significant increase of 0.83 [95% CL: 0.51 to 1.14, p<0.0000008] with 4% (6/167) of the children showing clinically significant wasting and 17% (29/167) being clinically overweight.

Figure 2: Testing for difference in between actual mean and an expected mean of zero.

Figure 3: Testing for difference in between actual mean and an expected weight of length P<0.0001.

Discussion

This study illustrated that the children in the sample were shorter and heavier than the expected curve described by the WHO. This is illustrated in Figure 3. We believe this is an illustration of the double burden of malnutrition, as defined by the WHO [4]. Further conclusions about the applicability of the Hasegawa et al screening tool in the setting of the community health worker needs further investigation. This tool did correctly score the underweight children surveyed in our sample as underweight. However, because there were not enough children in the sample with abnormal weights and heights, we were not able to perform predictive modelling to create a new model for the demographics of Southern Belize. Again, because of the small sample size, which would afford only highly unstable estimates, we were not able to perform predictive modelling to determine risk factors that put children at risk of having a double burden of malnutrition.

Strengths and Limitations

The value of a tool that can be utilized in the setting of CHWs, especially in rural communities, cannot be overstated. With a tool like the one analyzed here, CHWs have the potential to identify children at risk of malnutrition before the permanent effects of malnutrition affects a child’s life. Furthermore, the tool is simple to use and interviews can be conducted in a reasonable amount of time, making it feasible to use in many settings. Several of the anthropologic variables capture valuable data about the household and the community. For example, factors measuring clean water and access to plumbing do describe the income status of a family and the development of the community. With further research these variables could be a significant variable dictating the income status of a family and community and could translate to nutritional status of a child.

However, other anthropologic variables used in the screening tool may not be the most appropriate variable in every setting. This tool could be strengthened by adjusting the anthropologic variables on a cultural and community basis according to members of the community, local experts and officials. For example, this tool does little to assess the average family income which often affects the health of a family. The variable ‘head of household’ could, in some contexts, capture something about income status, however it translated poorly to the setting of rural Belize. The Mestizo and Mayan cultures are highly dominated by machismo, where the father is the head of the household even if he is not present in day-to-day life. This variable did little to assess income status in this study population and could be adjusted to better assess this. Furthermore, this tool does not assess how many children are present in each household. This factor would be highly valuable in a setting such as rural Belize to assess the economic burden of raising multiple children in an already low-resource setting.

Additionally, a limitation of this study was the sample method of convince sampling. Because of this, not all rural communities in the Independence catchment area were able to be assessed. Furthermore, the southern districts of Stann Creek and Toledo are much larger than the sample are. Because of the ethnic heterogenicity of Belize, it is challenging to extrapolate the findings here to the greater area at large. Further research should be aimed to expand the applicability of the tool to not only the study area, but the entirety of the southern districts.

Future Directions

The reason that the patterns seen in this study emerged are multifactorial. First, as previously mentioned, the area of Belize where this study was conducted is low income in comparison to the rest of the country. It is also a rural area, making resources scarce. This includes access to health care as well as access to healthy and affordable food. Much of the diet in these rural villages and communities surrounding polyclinics consists of processed food from local corner stores, fried foods and foods high in carbohydrates. Additionally, nutritional supplements, such as Incaparina, are usually given to children that are not meeting their growth requirements. This supplement is imported to Belize from Guatemala. It is often not available in the quantity needed by communities. Additionally, it is only distributed at the polyclinics and not at mobile clinics to rural villages. The lack of nutritional supplementation to the children of rural Belize is likely another contributing factor to the patterns seen in this study.

Conclusion

Further analysis is needed to identify the most significant factors affecting the double burden of malnutrition in southern rural Belize, however diet and access to foods is likely a significant variable.

Further research is needed to identify specific anthropologic variables that put children at risk of malnutrition, and the double burden of malnutrition in southern rural Belize. Once these factors are clearly delineated, policy and interventions by the Ministry of Health should be aimed to intervene early in a child’s life. This tool could serve as a vital detection device to capture children before the effects of malnutrition become irreversible.

Funding

The corresponding author received a small grant from the University of Miami Department Of Public Health for travel expenses. The funding body had no role in the design of the study or analysis.

Authors’ Contribution

First author, Reza Sheikhnejad (RS) has developed and formulated the experimental drug for this study, and carried out the in vitro tests as well. The second author, Farzaneh Ashrafi (FA) has directed the animal study and helped to design the protocol. The co-author, MN has designed and supervised the animal study; AT, has performed the pathology; BM and FM have carried out the animal study.

REFERENCES

- UNICEF UNCsF, Organization WH, for IB, Bank. RaDTW. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: key findings of the 2019 Edition of the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019.

- Hasegawa J, Ito YM, Yamauchi T. Development of a screening tool to predict malnutrition among children under two years old in Zambia. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1339981.

- Blossner M, De Onis M, Prüss-Üstün A. Malnutrition: quantifying the health impact at national and local levels. WHO; 2005.

- WHO Double Burden of Malnutrition: WHO. 2021.

- Belize Ministry of Health. Belize Health Sector Strategic Plan 2014-2024. 2014.

- Hersh J, Martín Rivero L, Engstrom R, Mann M, Mejía A. Mapping Income Poverty in Belize Using Satellite Features and Machine Learning. Inter-American Development Bank- Felipe Herrera Library. 2020.

- Abstract of Statistics Belize. In: Belize SIo, Editor. 2019.

- Abstracts of Statistics Belize. In: Belize SIo, Editor. 2013.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

- SAS Software. TS1M5 ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. 2017.

- Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing.2020.

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan L, François R, et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Softw. 2019;4(43):1686.

- Balise R, Odom G. Helper Functions for Working with REDCap Data. 2020.

- Firke S. janitor: Simple Tools for Examining and Cleaning Dirty Data. 2020.

- Schumacher D. anthro: Computation of the WHO Child Growth Standards. 2020.

- Komsta L, Novomestky F. Moments, cumulants, skewness, kurtosis and related tests. R package version. 2015;14.

- World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. World Health Organization. 2006.

- WHO. Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) country profile indicators: interpretation guide. 2010.

Citation: Brenner S, Balise R (2021) Evaluating Child Malnutrition in Southern Belize using an Anthropologic Screening Tool. J Vaccines Vaccin. 12:453.

Copyright: © 2021 Brenner S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.