Indexed In

- CiteFactor

- RefSeek

- Directory of Research Journal Indexing (DRJI)

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- Scholarsteer

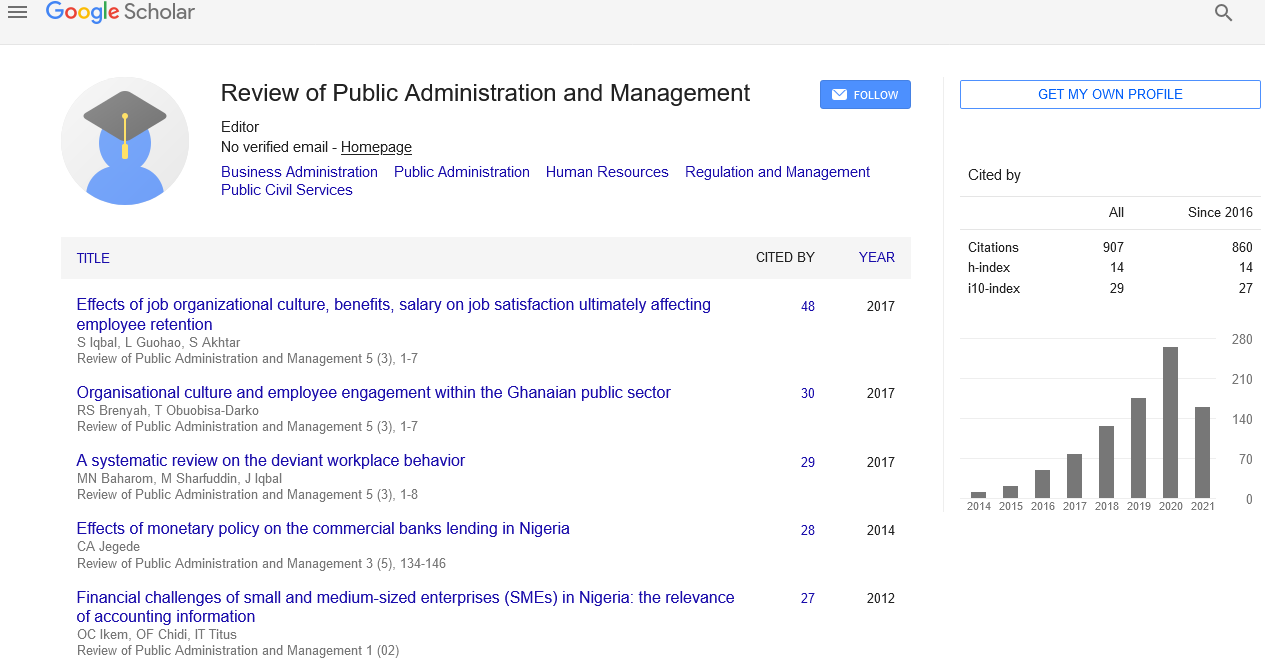

- Publons

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Editorial Note - (2021) Volume 9, Issue 9

Editorial Note on Youth Unemployment

Sonali Tiwari*Received: 15-Sep-2021 Published: 25-Sep-2021, DOI: 10.35248/2315-7844.21.9.302

Editorial

Unemployed refers to those who are unemployed for a set amount of time but are willing to work and have taken concrete actions to find paid work or self-employment. Unemployment among young people is a major stumbling block in the rising social disequilibrium that leads to economic chaos and poverty in society. On the one hand, India is a case of massive youth unemployment, while on the other; the nation is undergoing a transitional struggle to channel its energy into gainful alternate employment. High youth unemployment is directly related to a lack of education, training, and skills, as today's jobs demand a higher level of education and skill, which is not being passed down through the generations. High school dropouts have a jobless rate that is more than double that of university graduates. However, current statistics show that 96 million young people are unemployed, with 10 million new job seekers entering the market every year. As a result, the unemployment rate continues to rise day by day.

The Department of Youth Affairs and Sports, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, started a proposal to establish a National Youth Policy in 1985, the International Year of the Youth. Late in 1988, the National Youth Policy was introduced in both houses of Parliament. It has recognised that "elimination of unemployment, rural and urban, educated and uneducated" is "the most significant component of the youth programme." However, little concrete effort has been taken to achieve the goal of eliminating or at least reducing youth unemployment, as outlined in the National Youth Policy of 1988. The abovementioned reference to youth idealism in the National Agenda is likely to be scrutinised. The planned national rehabilitation corps, on the other hand, could be one way to address the problem of youth unemployment. However, a rigorous examination of the current data base and policy actions done thus far is required to assist build a comprehensive approach to youth problems and to evolve the necessary steps to alleviate youth unemployment. The current study tries to conduct the necessary review, focusing on the statistical data base made accessible by the National Sample Survey's numerous surveys.

India has a large proportion of the world's overall young population, with 540 million individuals under the age of 25 and nearly 200 million between the ages of 15 and 25. In terms of the quantity and relative percentage of youth in the population, different institutions, such as the Office of the Registrar General on behalf of the Planning Commission and the United Nations, have conflicting data. Youth made up roughly 18.5 to 19 percent of the national population in the early 1990s, according to best national estimates, and totalled around 159 million at the time of the 1991 Census. Over 53 percent of the 85 million people were employed.

The National Sample Survey Organization's data reveal that the youth unemployment rate, as assessed by different ideas, is 100 to 200 per cent higher than the general population average. In terms of weekly status, the unemployed young made up 40 to 50 percent of all rural unemployed and 58 to 60 percent of all urban unemployed. The absolute number of unemployed youth was between 5.5 and 8.6 million in 1987-88, and between 5.2 and 8.9 million in 1993-94, according to a range of estimates based on three alternate ideas. If the unemployment rate in terms of typical status remained constant during 2001, the number of unemployed people would increase.

The alarming increase in youth unemployment, as well as the equally concerning high numbers of young people who work but are still poor, demonstrate how difficult it will be to achieve the global goal of ending poverty by 2030 unless we redouble our efforts to achieve sustainable economic growth and decent work. “This research also reveals significant gaps in the labour market between young women and men, which must be addressed promptly by ILO member states and social partners,” said Deborah Greenfield, ILO Deputy Director-General for Policy.

When it comes to the subject of youth unemployment and the limitations of government intervention in India, It is not often understood that in a country with about 587,000 communities, the population is spread and that enforcing norms and laws is difficult. The reason for this is because in 1991, after 40 years of rapid population increase, 67 percent of India's villages had populations of less than 1000 people, with almost 3/5 of these villages having populations of less than 500 people. Although only 26 and 9.5 percent of the rural population lived in these settlements, they had larger proportions of scheduled tribes. There would be less than 100 youth in each of these communities with populations of less than 500.

Citation: Tiwari S (2021) Editorial Note on Youth Unemployment. Review Pub Administration Manag. 9:302.

Copyright: © 2021 Tiwari S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.