Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

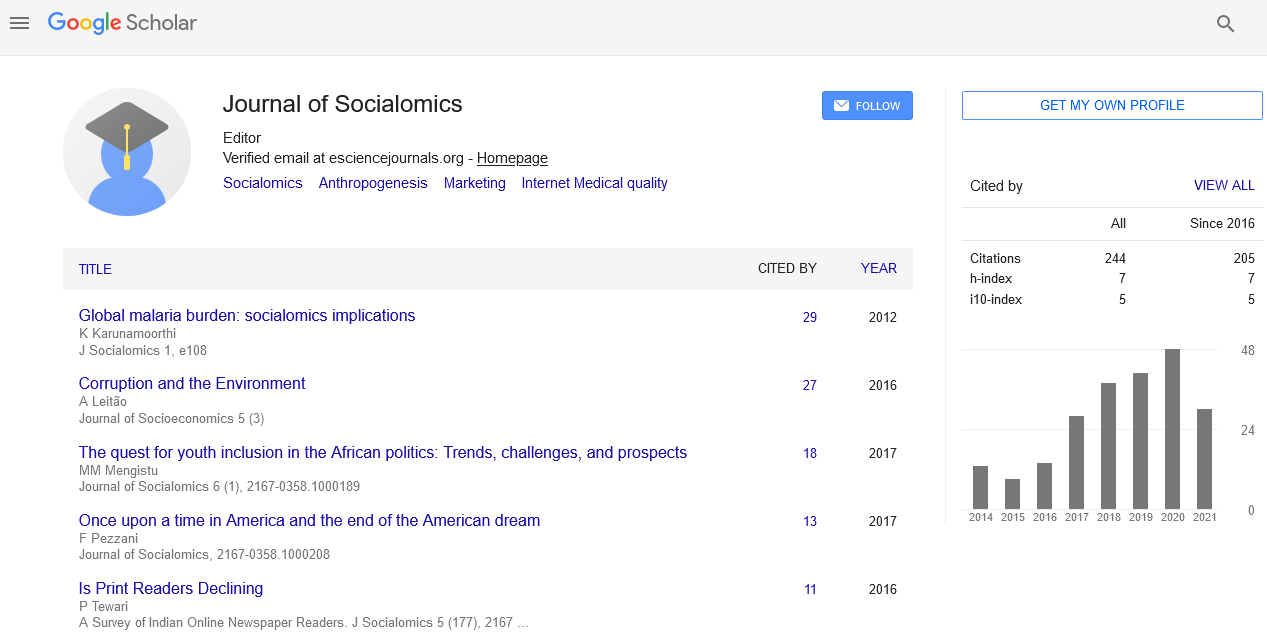

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Review Article - (2024) Volume 13, Issue 1

Does Lewiâs Contextualism Effectively Address the Gettier Problem? A Critical Analysis of David Lewis's Epistemic Contextualism

Khanh Trinh*Received: 17-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. JSC-23-23958; Editor assigned: 20-Nov-2023, Pre QC No. JSC-23-23958 (PQ); Reviewed: 04-Dec-2023, QC No. JSC-23-23958; Revised: 11-Dec-2023, Manuscript No. JSC-23-23958 (R); Published: 18-Dec-2023, DOI: 10.35248/2155-9627.23.12.224

Abstract

What makes knowledge possible? Can we be sure that the things we believe are true? Traditional epistemologists see knowledge as Justified True Belief (JTB). However, this theory has a severe problem, which Edmund Gettier pointed out and challenged in his three-page articles about the traditional analysis of knowledge in 1963. Contextualists with regard to knowledge argue that the truth of the claim 'S knows that P' is contextually dependent is one of the solutions that many philosophers propose to solve the problems in Gettier's cases. Among them, David Lewis, in his paper Elusive Knowledge, proposes a solution to the Gettier problem with the rules of relevance. In this paper, Khanh Trinh will attempt to investigate whether Lewis’s contextualism can offer a satisfactory explanation of Gettier's scenarios. In the first part, Khanh Trinh will provide a concise overview of Gettier problems. Second, Khanh Trinh analyzes how Lewis’s version of contextualism solves the Gettier problem. Third, Khanh Trinh will offer a critique of Lewis's assertion that epistemic contextualism can provide a satisfactory explanation for Gettier problems. In conclusion, Khanh Trinh asserts that Lewis's contextualism fails to address the challenges posed by the Gettier dilemma adequately. Epistemic contextualism, as proposed by Lewis, offers a partial resolution to the Gettier problem.

Keywords

Epistemology; Gettier problem; Contextualism; Justified true belief; Skepticism

Introduction

Gettier challenges the traditional theory of knowledge in his famous paper is Justified True Belief Knowledge. Many epistemologists after Gettier sought an alternative perspective to address these concerns. Numerous philosophers often suggest contextualism as a prospective resolution to address the challenges presented in Gettier's cases. This paper aims to explore Lewi’s contextualism in order to assess its effectiveness in resolving the Gettier problem. This will be accomplished by thoroughly analyzing how Gettier cases challenge the traditional theory of knowledge in the first section. In the second section, Khanh Trinh will analyze David Lewis’s contextualism effectiveness as a possible solution to the epistemological problem posed by Gettier. In the third section, Khanh Trinh gives some critiques of Lewis's contextualism, which offers a limited resolution in addressing the Gettier dilemma by highlighting its deficiencies. Khanh Trinh concludes that Lewis’s contextualist gives a partial solution to Gettier's problems.

Literature Review

Gettier's counter-examples

In his article Is Justified True Belief Knowledge? Edmund L. Gettier presented examples that illustrate situations in which Justified True Belief (JTB) is present, yet it is evident that knowledge is lacking. These examples challenge the efficacy of the Justified True Belief theory of knowledge is called the “Gettier problem”. The Gettier problem shows how an individual can meet the classical analysis of knowledge criteria, namely justified true belief, yet still lacking genuine knowledge. Gettier’s cases show that a justified true belief is true by chance. This implies that the three conditions of JTB. Do not guarantee knowledge.

Gettier says that in his two counter examples, a proposition can meet all three conditions of knowledge and still not be knowledge. According to Gettier, the justification present in each case is deemed to be fallible. In other words, the justification allows for the possibility of false belief. The main idea behind Gettier's counter-example is that a person can have a valid but false belief P, and because of P, he is also valid in believing a proposition that is true. Then, he can say that he has a true belief based on evidence but not knowledge [1]. We can structure the cases provided by Gettier in this way:

1. S believes that P.

2. S has sufficient but fallible justification for believing that P.

3. P is true.

4. S does not know that P.

According to the analysis put forth by Gettier, it is evident that the traditional tripartite definition of knowledge fails to provide a comprehensive framework for establishing knowledge, as it needs more conditions to do so. Gettier et al. argues that the Justification Truth and Belief (JTB) framework is not adequate for establishing the truth of a proposition. Hence, the counter examples put forth by Gettier appear to present a substantial obstacle to the traditional understanding of knowledge [2]. In essence, it can be argued that the challenges posed by Gettier's problems are inherent to nearly all theories of knowledge that posit knowledge as comprising true belief in conjunction with an additional element [3]. In the next part, Khanh Trinh will discuss epistemic contextualism as a response to the Gettier problem.

Lewi’s contextualist deal with gettier cases

This section will begin with a recapitulation of epistemic contextualism followed by an examination of David Lewis's contextualism. In this analysis, Khanh Trinh gives an outline of how contextualists look at the idea of knowledge attributions from Lewis's point of view. Then, Khanh Trinh will evaluate the potential of Lewis's contextualism as a solution to the Gettier problem by employing the rules outlined in Lewis's account. Epistemic contextualism is the idea that the word ‘know’ or the truth values of knowledge ascriptions depend on the epistemic standards operative in the attributor's context [4-10]. According to contextualists, the meaning of an utterance can change depending on when and who says it. We can thus define epistemic contextualism as follows:

The truth-values of 'knowledge’-attributions may vary with the context of utterance, where this variance is traceable to the occurrence of 'know(s) p' and concern a distinctively epistemic factor [11].

Thus, contextualism theory argues that someone's knowledge does not change upon shifting their perspective or situation, but the truthfulness of the utterances does. It means that someone could perceive a statement as either true or false based on varying contextual factors. As a result, different situations create various epistemic settings, which in turn set different truth conditions for claims of knowledge. While skepticism focuses on the justifications for knowledge and the semantics of the language employed to convey that knowledge, contextualism directs its attention toward the context and language. In this case, the epistemic matter is either true or false depending on the situation, which leads to the following actions. So, it is important to know what is at stake or what the speaker stands to gain. This kind of pragmatic approach shows that knowledge is not just based on the context of the speech, but also on things that are useful in real life.

Contextualism could be understood in a broader sense in which contextualism means that whether Bill knows or whether Sarah's belief is reasonable depends on the situation [12]. Contextualism is also understood in a narrower sense. In this sense, the proposition (S knows that P or S is justified in believing P) has different truth conditions depending on the conversation context and factors like the importance of the error possibilities.

In brief, contextualism can be understood as an epistemological framework that examines the truthfulness of knowledge by considering the specific contexts in which the utterance is produced and the pragmatic concerns of a speaker. The value of truth may have different values if you look at it from different points of view, but knowledge remains the same. It will be discussed more in the next section, where Khanh Trinh focuses on Lewis's contextualism point of view.

Lewis’s contextualist account of knowledge ascriptions

As mentioned above, the Gettier problem is a tough challenge for the traditional theory of knowledge. However, the problem of skepticism and the Gettier problem are not problems for some contextualists. In other words, contextualists say contextualism can solve the skeptical and Gettier problems [5,8,10,13]. Especially, Lewis in his paper, Exclusive Knowledge, has proposed that contextualism has the potential to address both the challenges posed by skepticism and the issues raised by the Gettier problem since Gettier cases have two errors confusions of contextual knowledge with non-contextual knowledge and confusions of a cognizor’s context with an attributor’s contextwhich will be fixed by epistemic contextualism [1].

Some clarifications: According to the traditional definition of knowledge, all things we know are at risk since we know that many possibilities have not been eliminated [10].

Therefore, beginning with the assumption of infallibilism, Lewis presents and elaborates upon a conceptualization of knowledge as follows:

Subject S knows that P if P holds in every possibility left uneliminated by S's evidence; equivalently, if S's evidence eliminates every possibility in which not-P [10]. According to Lewis, the concept of "every possibility" does not include all possibilities within logical space, but rather only those that hold relevance to the truth of a given knowledge statement.

Therefore, on the next page, Lewis revises his definition by adding a 'sotto voce proviso:

S (Subject) knows that P if S's evidence eliminates every possibility in which not P- Psst!-except for those possibilities that we (attributor and hearer) are properly ignoring [10].

The term of utmost importance in the aforementioned definition is 'properly ignoring.' The act of ignoring something explicitly expresses the perspective of contextualism in relation to the attribution of knowledge. Therefore, to comprehend Lewis's account correctly, we must thoroughly analyze this concept. Generally speaking, 'ignoring' could be understood in two ways. In other words, ignoring has two meanings: involuntary ignoring or unaware and voluntary ignoring or deliberate. In the first sense, when we say that S ignores P, it might mean that S is not aware of P or S is unconscious of P. This kind of ignoring is involuntary; in the latter sense, to say that S ignores P might mean that S does not want to deal with S, even though S is aware of P [14]. In Lewis's account, ignoring is understood mainly as the first kind – involuntary ignoring [15]. According to Lewis's definition, it is pointed out that we cannot choose to ignore all possibilities. If not, it would be very easy to achieve true ascription knowledge. In some cases or specific situations, some uneliminated possibilities can be properly ignored, while in others, we may not be properly ignored. These meanings give the verb "to know" a contextualist reading. Lewis comes up with a set of rules for "properly ignoring" things in order to help us figure out which possibilities we can properly ignore and which ones we cannot. In the following, Khanh Trinh will briefly introduce and discuss the rules.

Lewis's list of rules

Lewis proposed a categorization of seven rules, which can be further classified into two distinct groups. For Lewis, the first category of rules consists of four prohibitive rules (Rule of Actuality, Rule of Belief, Rule of Resemblance, and Rule of Attention) that delineate what must not be properly ignored. The second category comprises permissive rules consisting of three specific rules (Rule of Reliability, Rule of Method, and Rule of Conservatism) that indicate the permissible actions or conditions that may be properly ignored. This paper mainly focuses on the four prohibitive rules. The rest are not relevant and do not require further discussion in this paper.

The rule of actuality: "The possibility that actually obtains is never properly ignored" [10]. According to this rule, if a possibility that not-p is actual then the attributor can never properly ignore it. Therefore, nothing false is ever known. In other words, we cannot know p if p is false.

The rule of belief: "A possibility that the subject believes to obtain is not properly ignored, whether or not he is right to so believe". According to Lewis, what is believed or should be believed cannot be properly ignored. We cannot know something if we do believe the opposite. The level of belief that makes it impossible to ignore properly may change depending on the situation.

The rule of attention: "A possibility not ignored at all is ipso facto not properly ignored. What is not being ignored is a feature of the particular conversation context. No matter how far-fetched a certain possibility may be, no matter how properly we might have ignored it in some other context, if in this context we are not ignoring it but attending to it, then for us now, it is a relevant alternative". This rule says that the attributor cannot properly ignore the possibility of not-P, which he is attending. In other words, if a possibility' c' is attended to in 'D,' then c is relevant in D. Lewis claims that this rule is ‘‘more a triviality than a rule.”

The rule of resemblance states that if "one possibility saliently resembles another. Then if one of them may not be properly ignored, neither may the other". According to Lewis, if one of two similar possibilities is not being ignored according to the previous three rules, then the other possibility is also not being ignored. This rule will be used to overturn the Gettier cases.

Lewis's treatment of the gettier problem

Lewis' relevant alternative contextualism says that there are two ways to know something: by ruling out possibilities and not being aware of the chance of making a mistake. He also contends that there are some possibilities that cannot be eliminated but can be properly ignored. The above set of rules tells us which possibilities cannot be ignored, and there is no Gettier situation [16]. In this section, Khanh Trinh will examine how Lewis's rule solves the Gettier problem by focusing on prohibitive rules.

In "Elusive Knowledge", Lewis argues that his three restrictive rules, namely the rule of resemblance, the rule of actuality, and the rule of attention, can assist him in comprehending the underlying dynamics of Gettier cases and proposing potential solutions to the problem at hand. For Lewis, Gettier cases are solved because the Rule of Resemblance says that there must be a world where P is false and S's evidence cannot rule it out. By applying these rules, Lewis proposes that the Gettier problem in cases such as the Nogot-Havit case, fake barns cases, lottery cases, and the stopped clock case, which he emphasizes that very close resemblance of these cases to Gettier cases will be solved [10,17]. The following will examine how Lewis solves the lottery and Nogot-Havit cases.

The problem with the lottery paradox is that Bill bought a ticket in the fairy lottery. He cannot know ahead of time that he will lose, no matter how tiny the chances are that he will win. According to Lewis's definition of knowledge and his prohibitive rules, when Bill decides that he will lose the lottery, he does not think about the chance that he can win. However, this possibility cannot be ignored. What is the reason? The main reason is that each ticket has an equal chance of winning, and since each ticket has an equal chance of winning, one of the tickets will actually win. There is an equal chance (albeit a small one) that Bill's ticket will win like any other tickets. After all, Bill cannot deny the possibility that his ticket will win because of the Rule of Actuality. In light of this, Bill cannot exclude the possibility that his ticket will win by the Rule of Resemblance. According to Lewis' definition of knowledge, Bill does not know that his ticket will not win, because this possibility excludes his winning [18].

In the Nogot-Havit case, assuming that Khanh Trinh believes either Nogot or Havit owns a vehicle. Khanh Trinh believed that Nogot is the owner of vehicle a because he has seen Nogot driving a vehicle, whereas there is no evidence to suggest that Havit is the owner of a vehicle. I's conclusion is based on his observation of Nogot driving a vehicle. Having said that, let us presume that Nogot does not possess any vehicle. It turns out that he had rented the vehicle that he was driving. In addition, Khanh Trinh never saw Havit driving, but it turns out that Havit is the one who owns the vehicle. Then, Khanh Trinh believe that either Nogot or Havit owns a vehicle is true since (in reality, Havit owns a vehicle), and this true belief is also justified because Khanh Trinh witness that Nogot drives a vehicle every day. However, it (this true belief justified) is not knowledge. Therefore, Khanh Trinh does not know that either Nogot or Havit owns a vehicle. Why Khanh Trinh cannot achieve knowledge in this case?

According to Lewis, Khanh Trinh wrong do not know who owns a vehicle because from the point of view of a knowledge attributor, Khanh Trinh do not consider the possibility that Nogot drives a vehicle but he does not own it while Havit does not drive or own a car. Why this possibility cannot be properly ignored? Lewis argues that as in the lottery paradox, these dual possibilities saliently resemble actuality. The first rule says that the possibility that happens to be actual is never properly ignored. Nogot is a perfect closeness of actuality, whereas Havit is not true, but similar to actuality in two ways: Havit does not drive a car, and people who do not drive a car tend not to own one. Khanh Trinh does not know whether Havit or Nogot has a car, but he cannot rule out the possibility that both of them do not have a car. Khanh Trinh does not know whether Nogot or Havit has a car.

Rule of Resemblance says that the two possibilities are very similar to each other, so Khanh Trinh cannot ignore the possibility that Nogot drives his own car and Havit does not drive or own a car. Khanh Trinh cannot properly ignore this possibility based on his evidence and because I believe it is a Rule of Belief.

By involving the same rules with the same explanation, Lewis contends that the fake barn cases will be treated as follows: On the journey through the land of fake barns, Henry comes across only a few real barns. Henry has no idea what happened. His first thought is that what he sees is a barn, and he comes to believe it is a barn. So, Henry is looking at a real barn, but he could be seeing a fake one because there are a lot of them in that area. That is why it is incorrect to say Henry knows he is seeing a real barn [19]. On Lewis’s account, Henry lacks knowledge since he cannot properly ignore the possibility that he is looking at one of many fake barns in the land. This possibility cannot be ignored because it resembles actuality.

Lewis also uses the Rule of Attention to develop a theory about how "know" works in different situations. He says we can have various knowledge claims in different conversational settings by focusing on different possibilities. In this way, we can focus on different possible outcomes, which can help us see the different ways we "know" things in different situations [14]. Li gives an example regarding the Rule of Attention:

1. John knows that (Phil) hits Jack.

2. John knows that Phil (hits) Jack.

According to Li, both statements (1,2) can be true from their respective contexts because they are attended to different alternative possibilities. The first statement is true because John has strong evidence to exclude other possibilities (Peter hits Jack, Paul hits Jack). The second statement is also correct since John has good evidence to rule out other options, such as Peter hugs Jack, Paul hits Jack. Therefore, we can say that John knows that (Phil) hits Jack, although, of course, John does not know that Phil (hits) Jack. This rule can be used to solve the Gettier problem in the case of the lottery paradox in a way that is more effective and satisfactory than the solution that Lewis offered through the Rule of Resemblance [20].

Petty asserts that we can also use the Rule of Attention as a solution to the lottery cases as follows. Assuming that Janes buys a lottery ticket. She focuses on the lottery, which is a set of possible outcomes based on how the numbers are drawn. If Janes buys a lottery ticket, she automatically thinks about the chance that she will win. She thinks of it as one of a number of possible outcomes, or ways the lottery could go, not necessarily as her winning ticket. Janes does not know that she will lose since she is focused on or attended to the lottery and is thinking about the chance she will win (81).

At this point, Lewis’s version of contextualism seems to be a potentially fruitful epistemological framework. This point of view effectively minimizes skeptical outcomes. In addition, it preserves the criteria for truth condition. Notably, this approach successfully resolves both Gettier and lottery cases. Nevertheless, some critics contend this perspective is overly optimistic [20].

Critiques of Lewis' epistemic contextualism

There are several problems with using the rule of relevance to account for epistemic context changes. This section will offer some arguments that are raised against Lewis' arguments. Firstly, in his article titled "Contextualist Solutions to Epistemological Problems:

Scepticism, Gettier, and the Lottery," Steward Cohen presents an argument asserting that Lewis's Rule of Resemblance fails to solve Gettier problems effectively:

Because of the salience qualification, the Rule of Resemblance is speaker-sensitive. (We have seen that it is also subject-sensitive). This means that features of the context of ascription-facts concerning what resemblances are salient to the speaker (and hearers)-will determine which possibilities cannot, by this rule, be properly ignored. This aspect of the Rule of Resemblance, Khanh Trinh shall argue, leads to a serious difficulty for Lewis’s treatment of the Gettier problem [4].

Cohen contends that the Rule of Resemblance in Lewis’s account cannot solve Gettier's problems since the resemblances are required to be salient as its definition (Lewis, 1996: p. 565). According to Cohen, salient can be understood in two ways: speaker salience (speaker-sensitive) and subject salience (subjectsensitive). The resemblance is salient to the speaker when a feature of a possibility is somehow important to the speaker. When a feature of a possibility is somehow important to the subject, it is the subject salience [4].

Cohen emphasizes that in all Gettier cases, the subject is unaware of being in a Gettier situation. If he knows he is in a Gettier case-subject salience, there is no more a Gettier case. Therefore, it is impossible for the Rule of Resemblances to solve Gettier problems when the resemblance is salient to the subject. In order to solve Gettier problems, the Rule of Resemblance's kind of salience operant must be speaker salience (ibid.). To illustrate how the rule of Resemblance (the speaker salience) solves Gettier cases, Petty adapted Cohen’s sheep on a hill example to show the problem as follows:

S is looking at a sheep-shaped rock on a hill behind which there happens to be a sheep. F, who is far away from S, can see that S is in a Gettier situation. F claims that S fails to know that there’s a sheep on the hill [20].

In this case, the sheep-shaped rock is irrelevant to S, and the subject S is in a Gettier situation. S would not be in a Gettier situation if S knew about a rock that looks like a sheep. Whereas, the sheep-shaped rock is salient to speaker F since F knows that S is in a Gettier situation. From speaker F’s point of view, we can apply the Rule of Resemblance to solve Gettier problems as Lewis proposed. According to the Rule of Resemblance, the possibility of the sheep-shaped rock is relevant because it looks like the real possibility (real sheep). The sheepshaped rock looks like a sheep cannot be ruled out or ignored, so S does not know there is a sheep on the hill. Petty concludes that if all instances of Gettier cases were similar to the one mentioned earlier the resemblance is speaker salience, it is plausible that Lewis could have potentially resolved Gettier's problem. However, Cohen argues that Lewis faces a challenge in that there is nothing to guarantee that resemblance will be salient. It is possible that the resemblance is salient in some contexts, but it could not be salient in others. The not-P possibility will be properly ignored when the resemblance is not salient, and the subject will know [4]. Furthermore, he pointed out that the relevant resemblance may fail to be speaker salience in his alternative version of the sheep on the hill in which both subject and speaker are unaware that the subject is in a Gettier situation:

S is looking at a rock on a hill that looks like a sheep. Behind the rock, there is a sheep. A is in the same scene as S. However, both S and A think they are seeing a sheep rather than a sheepshaped rock. None of them knows that he is in a Gettier situation. A says, "S knows there is a sheep on the hill" [4].

In this case, the sheep shaped rock is not salient to both the speaker and the subject. Since in this case, no one thinks there is a rock in the shape of a sheep, everyone thinks it is a sheep. The rock in the shape of a sheep is not important to anyone. Therefore, there is no way to use the Rule of Resemblance to explain why there is a hill without sheep and a rock in the shape of a sheep. So, Cohen says that Lewis claims there is a sheep on the hill, even though S in a Gettier situation is not satisfactory since salience is a requirement of the Rule of Resemblance [20]. In other words, Lewis’s account of contextualism with the Rule of Resemblance cannot solve the Gettier problem.

The second argument about the rule of Attention. On Lewis’s account, this rule states that “ignoring a possibility” means actually ignoring it, rather than merely having the potential to ignore it but choosing not to do so. It means that we can ignore a possibility if we do not mention or talk about it or draw attention to it in any way. When we draw attention to a possibility, it cannot be ignored anymore, and a fortiori a fortiori is not ignored properly [21]. Given this rule, it seems that Gettiers problems, such as a fake barn case and a sheep shaped rock case, no longer exist. For example, in the context of the sheep-shaped rock case, the potential existence of a rock resembling a sheep is brought up as a relevant consideration when examining the entailment. By acknowledging the potential existence of a rock resembling a sheep, one is compelled to consider this possibility and cannot reasonably disregard it thereafter. However, according to Baker, Lewis faces another problem with this rule. If someone in a conversation brings up a possibility, even if they do so by accident, it cannot be ignored anymore, even if everyone has been ignoring it before. Stopping this possibility from happening again can only be done by starting to ignore it again. However, it is a mistake. Why do we talk about something and then agree that what we did was wrong? Baker concludes that Lewis's explanation is to assert that the rule of attention merges psychological factors with epistemic factors. Specifically, it combines the psychological aspect (what we can or have disregarded in a psychological and contingent manner) with the epistemological aspect (what we are permitted to ignore from an epistemic standpoint). The determination of what is considered "proper" or not, from an epistemological perspective, should be unaffected by the contingent thoughts that enter my mind [22-24].

Other objections come from Oakley in which he contends that the Rule of Attention leads to contradictions. In the previous section, Khanh Trinh discussed that the Rule of Attention could show us the different ways we "know" things in different situations when we change our focus to different possible outcomes (in the example: Although John knows that (Phil) hits Jack, John does not know that Phil (hits) Jack.). Oakley provides examples that illustrate the application of the Rule of Attention, revealing instances where two individuals may make seemingly contradictory knowledge ascriptions and denials. He claims that the Rule of Attention necessitates acknowledging the possibility of both affirmation and negation being valid. In other words, many agreements about knowledge ascriptions were only apparent and not real because of the Rule of Attention. Therefore, we should reject the Rule of Attention.

Another argument against Lewis's claim that lottery cases and fake barns are similar to Gettier cases was made by Delia Belleri and Annalisa Coliva in The Gettier Problem and Context. According to Lewis, Gettier cases are very similar to Lottery cases and fake barns. This means that if we can use a set of rules to solve the problem in these cases, it must also work in the Gettier cases. Belleri and Coliva contend that the lottery cases and Gettier cases are not similar. Using Pritchard's concept of veritic epistemic luck, Belleri and Coliva claim that luck is the central point in Gettier cases, while it is absent in the lottery cases. For Duncan Pritchard there are some kinds of luck that are good for us, while others are bad. It does not threaten knowledge if someone learns something by accident or through luck, but it does threaten knowledge if someone believes something that was based on luck and could have been wrong. As an illustration, an individual A might think that 8:29 really is 8:29, which would mean that his belief is true by chance because the real world has a possibility that is not present in nearby worlds. On the other hand, in the context of lottery cases, B knows that his ticket will not win based on the lottery statistics, but B's belief is not lucky. In this case, B has a true belief that he is not lucky, but it is not knowledge [17]. The lottery cases are not the same as Gettier cases, so Lewis's solution for lottery cases cannot be used for Gettier cases. This means the Gettier problem is still a big problem for Lewis's contextualism [10].

The section's conclusion posits that Lewis's contextualism enables the acquisition of knowledge without elimination, achieved through deliberately disregarding certain factors. Lewis establishes a framework consisting of various rules, namely the Rule of Actuality, Rule of Resemblance, and Rule of Attention, to illustrate the existence of uneliminated knowledge that aids in addressing the challenges posed by Gettier. However, Lewis's proposed solution does not fully satisfy the Gettier problem due to the remaining issues concerning the Rule of Attention and Rule of Resemblance and Lewis's confusion between lottery cases and Gettier cases [25-30].

Conclusion

In this paper, Khanh Trinh showed that David Lewis, a prominent figure in the field of contextualism, presents a solution to the Gettier problem in his paper titled "Elusive Knowledge." In this work, Lewis argues that the Gettier problem does not challenge his contextualism framework, which he developed by formulating two sets of rules. Notably, the prohibitive rule encompasses the Rule of Actuality, the Rule of Resemblance, and the Rule of Attention. Lewis demonstrates that three specific constraints can offer a satisfactory resolution to the issues of lottery cases, fake barns, and certain cases that he assumes closely resemble Gettier's cases. However, Lewis's rules also exhibit certain limitations raised by objections from other scholars regarding the Rule of Resemblance and the Rule of Attention. Upon carefully examining the various perspectives and thoroughly evaluating the available evidence and arguments, Khanh Trinh contend that Lewis's contextualism does not offer a comprehensive resolution to the Gettier problem but presents a partial solution to this philosophical quandary.

References

- Jianbo C. A critique to the significance of Gettier counter-examples. Front Philos China. 2006;1(4):675-687.

- Gettier EL. Is justified true belief knowledge?. Analysis. 1963; 23(6):121-123.

- Zagzebski L. The inescapability of Gettier problems. The Philos Q. 1994; 44(174):65-73.

- Cohen S. How to be a Fallibilist. Philos Perspect. 1988:581-605.

- Cohen S. Contextualist solutions to epistemological problems: Scepticism, Gettier, and the lottery. Australas J Philos. 1998; 76(2):289-306.

- Cohen S. Contextualism, skepticism, and the structure of reasons. Philos Perspect. 1999; 13(1):57-89.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- De Rose K. Contextualism and knowledge attributions. Philos Phenomenol Res. 1992; 52(4):913-929.

- De Rose K. Solving the skeptical problem. The Philos Rev. 1995; 104(1):1-52.

- De Rose K. Contextualism: An explanation and defense. The Blackwell guide to epistemology. 2017; 19(1):187-205.

- Lewis DE. Elusive knowledge. Australas J Philos. 1996; 74(4):549–567.

- Blome-Tillmann M. The semantics of knowledge attributions. Oxford University Press; 2022.

- McKenna R. Contextualism in Epistemology. Analysis. 2015; 75(3):489-503.

- Stine GC. Skepticism, relevant alternatives, and deductive closure. Philos Stud. 1976;29(1):249-261.

- Li Q. Subject-sensitive invariantism and the knowledge norm for practical reasoning. McMaster University. 2012.

[Crossref]

- Oakley IT. A skeptic's reply to Lewisian contextualism. Can J Philos. 2001; 31(3):309-332.

- Brogaard B. Contextualism, skepticism, and the Gettier problem. Synthese. 2004;139 (1):367-386.

- Belleri D, Coliva A. The Gettier problem and context. In the Gettier Problem Cambridge University Press. 2018: 78-95.

- Gutting G. What philosophers know: Case studies in recent analytic philosophy? Cambridge University Press. 2009.

- Goldman AI. Discrimination and perceptual knowledge. The J Philos. 1976; 73(20):771-791.

- Petty JM. Brains and barns: The role of context in epistemic attribution. University of Massachusetts Amherst. 2004.

- Brendel E, Jager C, Barke A. Contextualisms in epistemology. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. 2005.

- Foucault M. The archaeology of knowledge. Pantheon. 2013.

- Hawthorne J. Knowledge and lotteries. Oxford University Press, USA; 2004.

- Hospers J. An introduction to philosophical analysis. Routledge. 2013.

- Longino HE. The fate of knowledge. Princeton University Press. 2002.

- Moser PK, Vander Nat A. Human knowledge: Classical and contemporary approaches. Oxford University Press. 1987.

- Van Ormondt P. Finite narrative modelling, contextual dynamic semantics and Elusive Knowledge. Universiteit van Amsterdam.2012.

- Rorty R. Philosophy and the mirror of nature. Princeton university press. 2009.

- Shope RK. Cognitive abilities, conditionals, and knowledge: A response to Nozick. The J Philos. 1984; 81(1):29-48.

- Wittgenstein L. On certainty. Oxford University. 1969.

Citation: Trinh K (2023) Does Lewi’s Contextualism Effectively Addresses the Gettier Problem? A Critical Analysis of David Lewis's Epistemic Contextualism. J Socialomics. 13:224.

Copyright: © 2024 Trinh K. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.