Indexed In

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2019) Volume 22, Issue 2

Aquaculture Operation in Allocated Mangrove Areas in Kien Giang, Vietnam: Local Perceptions and Recommendations

Thai Thanh Luom*Received: 23-May-2019 Published: 19-Jun-2019

Abstract

Allocation of coastal mangrove areas for protection and livelihood improvement has been adopted as a management practice in Kien Giang and the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. However, allocated mangrove forests were eroded and ponds were abandoned. The literature reveals that there was a low level of local involvement in mangrove planning and management and limited understanding of the policy among the contractees in Kien Giang. The Kien Giang mangrove allocation policy needs to be revised as legally required. The voice of the contractees need to be heard because the contractees have been involved in protecting coastal mangrove forests since 2005. In addition, a sound policy needs to integrate all sources of knowledge during the policy making process. This study aims to adequately understand local perceptions of the status of their aquaculture ponds and aspirations for improving the efficacy of aquaculture pond operation. The study was undertaken using mixed methods, with the Kien Giang contractees’ involvement as co-investigators. The results show that the contractees believed that their ponds were jeopardized by natural factors, not their operation activities. Improper pond construction techniques significantly contributed to erosion, worsening the consequences of natural factors, breaking their ponds and forcing them to leave their ponds abandoned. The contractees at the end of the study became fully aware of the consequences of their improper pond operation activities. The contractees could not afford costs of proper protection or reconstruction of abandoned ponds to revive their livelihood incomes. Allocated mangrove areas should be configured at a more proper ratio to ensure the protection of, and sustainable use of, allocated mangrove forests for aquaculture purposes.

Keywords

Allocated mangrove areas; Aquaculture ponds; Kien Giang; Mangrove belt; Livelihood improvement

Introduction

The 2004 Law on Forest Protection and Development, promulgated by the Vietnam National Assembly in 2004, stipulates three types of forests that include special use forests, protection forests and production forests. Human activities in special use and protection forests need permission from competent government agencies [1]. Since 2001, forests in protected areas in Vietnam have been officially allocated to local community members who are dependent on forest resources for protection and local livelihood improvement [2].

The Kien Giang coastal mangrove protected area is classified as a protection forest (Vietnamese National Assembly 2004). Kien Giang province applied the 2001 allocation policy by Vietna mese Prime Minister for allocating coastal mangrove forests to local communities for protection and livelihood improvement in 2005. Local coastal communities were legally permitted to be involved under contracts in protecting coastal mangroves on the 70% of allocated areas in return to use the 30% for integrated aquaculture farming. Contracts, issued by the Management Boards (contractors), were signed by households, organizations, and individuals residing in Kien Giang Province (contractees) [3]. The 2005 Kien Giang policy was updated in 2011. The 2011 Kien Giang policy continued to promote the 30 (use)/70 (protection) allocation [4]. Nguyen et al. reported that contractees had limited understanding of the policy that resulted in ineffective and inefficient aquaculture and mangrove protection in almost all areas [5]. At the same time, mangroves were not well protected. Aquaculture ponds and agriculture areas were lost as a consequence of coastal erosion, causing significant economic loss for local contractees [6]. Nguyen et al. reported that there was a low level of local involvement in mangrove planning and management [5].

Kien Giang was projected to be negatively affected by sea level rise and climate change [7-9]. In 2012, a 500 m continuous mangrove belt has been planned to be established along the Kien Giang coast that could adapt to climate change and projected sea level rise [4,10]. Protection of mangrove areas and livelihoods in Kien Giang is a shared responsibility for local communities and the Kien Giang PPC. The 30 (use)/70 (protection) allocation is the mandate that cannot be changed. The 2011 Kien Giang policy needed to be reviewed, as is legally required.

Taking into consideration the issues discussed above, the Kien Giang coastal mangrove protected area is not effectively managed and the 500 m mangrove belt is not established if the situation still persists. The voice of the Kien Giang contractees should be properly heard during the policy making process because [11] indicates that local communities are a key contributor to ensuring sustainable development. A sound policy is formed using a variety of knowledge sources [12]. The Kien Giang contractees should be fully consulted during the policy revision process as well as the development of the 500 m continuous mangrove belt. For the time being, there has been limited knowledge of how the Kien Giang contractees perceive their aquaculture ponds and of what expectation they would like to have to improve the efficacy of aquaculture pond operation. This knowledge would be useful for revising the 2011 Kien Giang policy or developing technical guidelines on the 500 m mangrove belt program. Therefore, this study aims to adequately understand local perceptions of the status of their aquaculture ponds with respect to factors influencing the sustainability of aquaculture ponds for livelihood improvement and aspirations that the Kien Giang contractees might hold to improve the efficacy of aquaculture pond operation. The study was undertaken with the involvement by the Kien Giang contractees as co-investigators.

Material and Methods

Site description

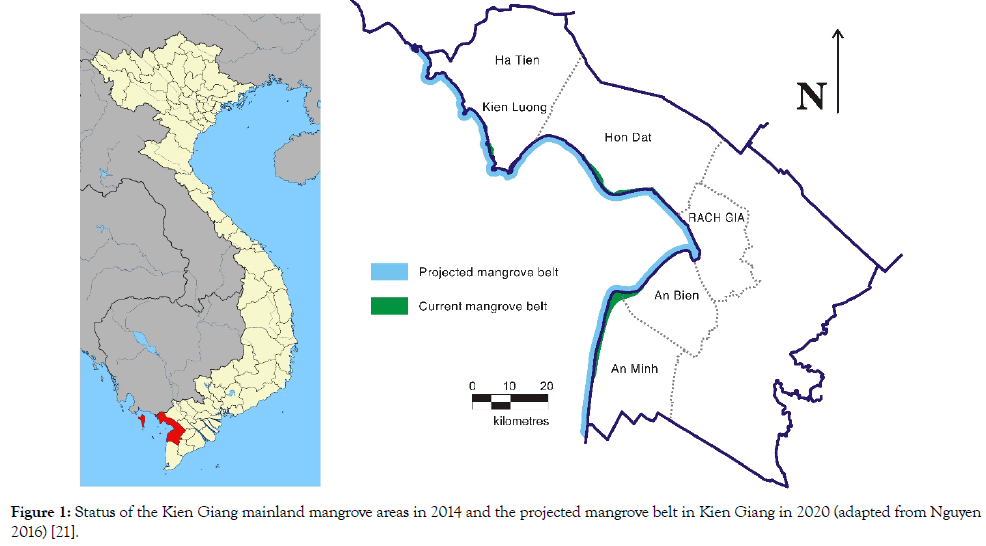

Kien Giang Province, located on the Mekong Delta region of Vietnam (Figure 1), is rich in mangrove species, with 27 of the 39 species reported to be found in Vietnam [13,14]. The Kien Giang coastal mangrove protected area has a total area of 6,951.8 hectares that stretch over four coastal districts, one town, and one city [15].

Figure 1: Status of the Kien Giang mainland mangrove areas in 2014 and the projected mangrove belt in Kien Giang in 2020 (adapted from Nguyen 2016) [21].

The Kien Giang coastal mangrove protected area is managed by two Management Boards that include the An Bien–An Minh Management Board and the Hon Dat–Kien-Ha Management Board, with support provided by the district level Departments of Forest Protection, the District People’s Committees, and Management Protection and Management People Units which were voluntarily established by local people in villages [10]. The Kien Giang coastal mangrove protected area is zoned into two ecological mangrove belts: the primary mangrove belt and secondary mangrove belt. The primary mangrove belt is strictly protected for improving resilience and protection of mangroves, while the secondary mangrove belt is managed for allocating mangroves to local communities for protection and livelihood improvement [10].

Methods

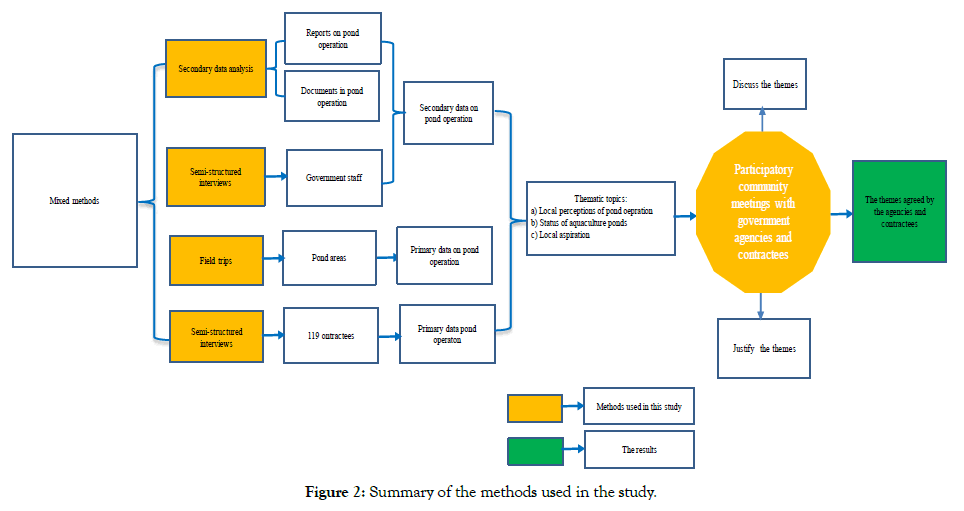

The study was undertaken between May 2015 and July 2016 using mixed methods [16]. Methods for data collection included secondary data analysis (a desk review) [17], semi-structured interviews [18], field visits (participant observation) [19]. Methods for data analysis were thematic analysis [20], and peer debriefings [17].

Secondary data including written reports and polices in relation to protection and uses of allocated mangroves for livelihood improvement were critically reviewed and analyzed using secondary data analysis method. Other secondary data which were not locally published were collected from various meetings organized with provincial agencies (DARD, Department of Natural Resource & Environment of Kien Giang Province, the An Bien – An Minh and Coastal Mangrove Management Board, Kien–Hai–Ha Coastal Mangrove Management Board, the District People’s Committees of An Bien, An Minh, Kien Luong and Hon Dat). Additional secondary data regarding mangrove and livelihood protection in Kien Giang were collected from semi-structure interviews. Six semistructured interviews were conducted with staff working for DARD and the two Management Boards.

Six field trips were organized by boat along the Kien Giang coastline using Google maps of the areas, maps of forestry planning and inventory, results provided by CDBRP [13,14] and maps of land use planning. During the field visits, the entire Kien Giang coastline was strategically assessed to view the vulnerability of coastal mangrove areas, as determined by the nature of coastal erosion to which they are exposed, the likelihood or frequency of occurrence of coastal erosion, the extent of erosion, and the sensitivity of the coastal areas to the impacts of the erosion.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 119 representative contractees of 11 communes of Kien Giang province. The 119 representative contractees were selected because they have lived in the areas for their life, and have operated aquaculture ponds since 2005. Questions that were used in semi-structured interviews focuses on local perspectives on factors influencing the sustainability of aquaculture ponds, and improving the efficacy of their aquaculture pond operation.

The secondary data and primary data were systematically categorized into themes that were used for discussion in meetings with local fishers and farmers and two Management Boards at a later stage. The themes included (a) Local perceptions of factors influencing the sustainability of aquaculture ponds, (b) The status of aquaculture ponds along the Kien Giang coastline; and (c) Aspirations of improving the efficacy of aquaculture ponds operation.

Eleven peer debriefings were held involving 325 contractees and private land owners, with administrative assistance from the Women’s Union, the Farmers’ Union, local government agencies and the two Management Boards. The themes were discussed and agreed in the meetings. The results gained from peer debriefings were validated by detailed minutes that were signed by the community representatives. The methods are summarized in (Figure 2). The results were presented in Section 3.

Figure 2: Summary of the methods used in the study.

Results

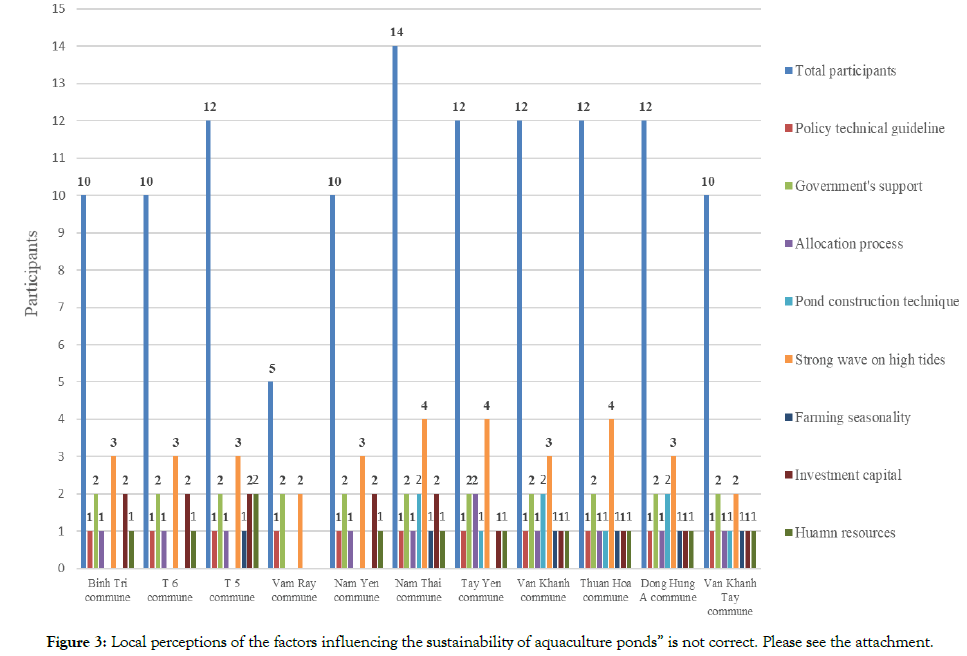

Local perspectives of factors influencing the sustainability of aquaculture ponds Of 8 factors identified influencing the sustainability of aquaculture ponds including policy technical guidelines, government’s support, allocation process, pond construction techniques, strong waves on high tides, farming seasonality, investment capital, and human resources. Strong waves on high tides is the most influencing factor to the sustainability of aquaculture ponds, followed by policy technical guidelines, and pond construction techniques (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Local perceptions of the factors influencing the sustainability of aquaculture ponds” is not correct. Please see the attachment.

The status of aquaculture ponds along the Kien Giang coastline

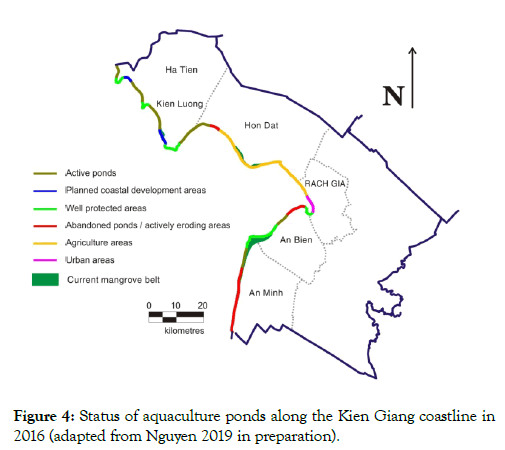

Up to 2016, the Kien Giang coastline remained severely eroded, with remnants of pond dykes and pond gates found along the shoreline on low tides, loss of mangrove vegetation, sea dykes breached, mangroves were degraded or deforested, especially with Rhizophora apiculata being uprooted. The coastline were dissected by ponds of all sizes and protected by a thin line of coastal mangroves, aquaculture ponds of all sizes exposed to the sea, and agriculture areas (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Status of aquaculture ponds along the Kien Giang coastline in 2016 (adapted from Nguyen 2019 in preparation).

Pond design and construction techniques

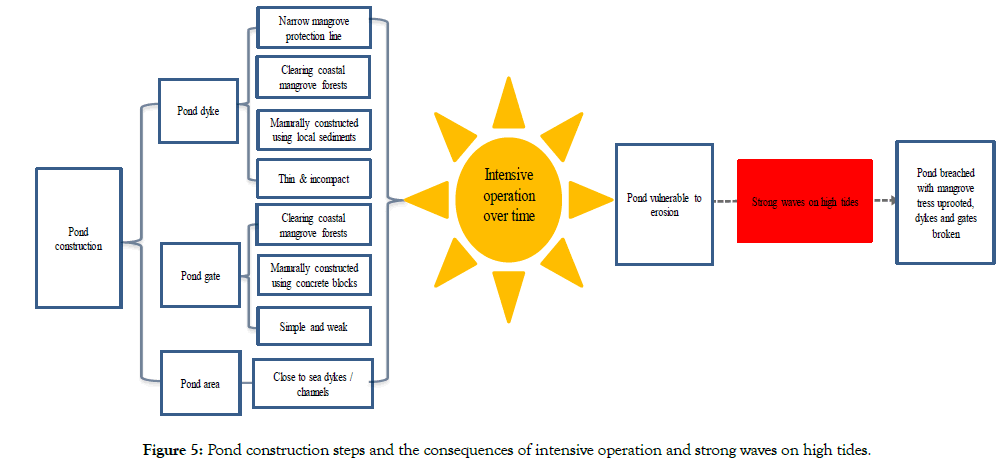

The semi-structured interviews with the Kien Giang contractees revealed that the contractees used their knowledge for constructing aquaculture ponds. Ponds were constructed in areas close to water areas. Gates were constructed along mangrove areas to allow the passage of sea water to ponds located far from water areas (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Pond construction steps and the consequences of intensive operation and strong waves on high tides.

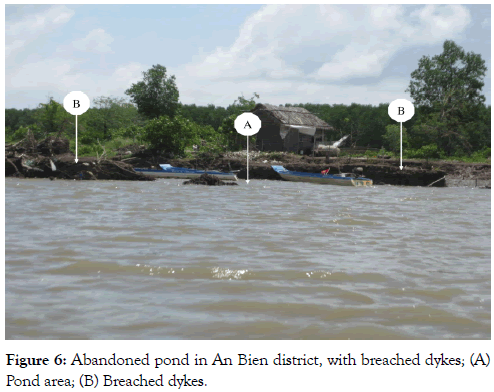

Ponds were breached in the 2000s. During the rainy season, strong waves on high tides uprooted mature trees of Rhizophora apiculata, breaching thin and incompact dykes and entering into pond areas. When breached, ponds were abandoned. Abandoned ponds were still seen along the Kien Giang coast in low tides (Figure 6). Ponds were abandoned because they were severely eroded and the contractees could not operate aquaculture ponds.

Figure 6: Abandoned pond in An Bien district, with breached dykes; (A) Pond area; (B) Breached dykes.

Local aspirations

The Kien Giang contractees were eventually sure that the current pond construction techniques resulted in their ponds being vulnerable to erosion or abandoned. Those whose ponds were not breached also became aware that if they keep using the same techniques, they will soon encounter the same consequences other contractees did. Proper protection of active ponds or the reconstruction of abandoned ponds would require significant capital investment and efforts. For the time being, they did not have access to local loan programmes or financial support from the governments at all levels. In some cases, the contractees could not afford reconstruction of their abandoned ponds. The contractees expressed that they need additional economic and technical support to secure their pond operation as well as to reconstruct their ponds for their livelihood improvement. The contractees wished that they are eligible to low interest loan programmes so that they afford aquaculture pond operation costs.

Discussion

Local involvement and the ownership of local issues

Previous attempts that advanced coastal mangrove and livelihood protection in Kien Giang Province were conducted by external specialists, recruited by CDBRP or government staff [23]. As a consequence, the Kien Giang contractees could not raise their voices on issues that mattered them. The less involved the Kien Giang contractees were in undertaking the attempts, the less chances they had for understanding their own problems. In this study, the Kien Giang contractees first perceived that their ponds were vulnerable to erosion mainly due to natural factors i.e. strong waves on high tides, while human induced activities such as policy technical guidelines, and pond construction techniques were not significant contributors. Figures 5 and 6 show that improper pond construction techniques worsen consequences of natural factors such as strong waves on high tides. Likewise, [24] confirmed the consequences.

Also in this study, the co-investigation undertaken by the Kien Giang contractees greatly assisted in understanding the severity of their own issues. According to [24] local ‘ownership’ of their own problems is possibly one of the highest levels of participation, and is likely to contribute to ensuring the sustainability and applicability of the solutions at the local level. A high level of participation, local ownership, and sustainability are needed in all development projects [11].

Transferring knowledge to other provinces in the lower Mekong Delta region and Vietnam

The findings of the study provided a valuable technical reference regarding aquaculture pond construction techniques and the interaction between the techniques and natural factors. The same pond construction techniques have become popular in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. This study indicates that if the same techniques are used in Kien Giang as well as the Mekong Delta region, the consequences would be highly likely to occur as that in Kien Giang. Kien Giang and other coastal provinces in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam promote the establishment of the 500 m mangrove belt along the Mekong Delta coast for adaptation to climate change and sea level rise [25]. Up to date, the 500 m mangrove belt has not been established either in Kien Giang or the Mekong Delta region [26,27]. Allocated mangrove areas in Kien Giang should be configured in a way that that comply with the 2011 Kien Giang mangrove allocation policy, which is to protect 70% of allocated mangrove areas on the seaward side in return for the use of aquaculture ponds, as suggested by [23]. If configured at the ratio of 70/30 as proposed, a continuous mangrove belt should be established, probably assisting in achieving the 2011 Kien Giang mangrove allocation policy and the establishment of the 500 m continuous mangrove belt as decided by Kien Giang PPC and for the entire Mekong Delta coast.

Conclusion

The Kien Giang contractees’ involvement was crucial in identifying factors influencing the sustainability of aquaculture ponds for livelihood improvement. Local perceptions of the status of aquaculture ponds have been recorded with the local understanding that their ponds were negatively affected by natural factors, not by their aquaculture pond operation and construction techniques. At the end of the study, the contractees all became fully aware that their techniques significantly contributed to the abandonment of their ponds. They would like to obtain technical and economic assistance that help protect their current ponds and reconstruct abandoned ponds for livelihood improvements. Allocated mangrove areas should be properly configured at a ratio of 70 (protection)/30 (use) to ensure proper protection of their ponds and achieve the objective of the Kien Giang allocation policy and the establishment of the 500 m mangrove belt along the Mekong Delta coast.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Commune People’s Committees of Tay Yen, Nam Yen, Nam Thai, Thuan Hoa, Dong Hung A, Van Khanh, Van Khanh Tay, Binh Giang, Binh Son, Binh Tri for their assistance in organizing community meetings.

REFERENCES

- The Forest Protection and Development Law in 2004 Hanoi: Vietnamese National Assembly. 2004.

- Vietnamese Prime Minister. The Decision re benefits and responsibilities of households and individuals provided, allocated or rented with forests and forestland. Hanoi: Vietnamese Prime Minister. 2001.

- Kien Giang PPC. The decision on issuing the mangrove protection and development in Kien Giang province. Rach Gia: Kien Giang PPC. 2005.

- Kien Giang PPC. The decision on issuing the regulations of mangrove planting, protection, and utilization in Kien Giang province. Rach Gia: Kien Giang PPC 2011.

- Nguyen TP, Luom TT, Parnell KE. Mangrove Allocation for Coastal Protection and Livelihood Improvement in Kien Giang Province, Vietnam: Constraints and Recommendations. Land Use Policy. 2017;63:401-407.

- Nguyen HH, Pullar D, Duke NC, Mcalpine C, Hien T, Hoa NH, et al. Historic shoreline changes: an indicator of coastal vulnerability for human land use and development in Kien Giang, Vietnam. In: 31st Asian Conference on Remote Sensing. 2010;1835-1843.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of Vietnam. Climate Change, Sea Level Rise Scenarios for Vietnam. Hanoi: Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Vietnam. 2010.

- Kien Giang PPC. Land use planning report with a vision up to 2020 and five year land use planning phase 1 (2011–2015). Rach Gia: Kien Giang PPC. 2010.

- Asian Development Bank. Climate Risks in the Mekong Delta: Ca Mau and Kien Giang provinces of Vietnam. Manila, the Philippines: Asian Development Bank 2010.

- DARD. The 2012-2016 Mangrove Rehabilitation and Development Project in Kien Giang province. Rach Gia: DARD. 2012.

- Anderson MB, Brown B, Jean I. Time to listen: Hearing People on the receiving end of international aid. Cambridge, Massachusetts: CDA Collaborative Learning Projects 2012; 144.

- Van Stigt R, Driessen PPJ, Spit TJM. A user perspective on the gap between science and decision-making. Local administrators’ views on expert knowledge in urban planning. Environmental Science & Policy 2015; 47:167-176.

- CDBRP. Biomass and Regeneration of Mangrove Vegetation in Kien Giang Province in 2010. Rach Gia: CDBRP.2010.

- CDBRP. Assessing mangrove forests, shoreline condition and feasibility of REDD for Kien Giang province. Rach Gia: CDBRP.2010.

- DARD. Report on preliminary results of the five year implementation of the decision 51 by Kien Giang PPC re coastal mangrove planting and protection in Kien Giang province. Rach Gia: DARD. 2010.

- Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative and quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publication. 2009.

- Schutt RK. Investigating the social world: the process and practice of research. Chapter 10: qualitative data analysis. London: SAGE Publications.2009.

- Ayres L. Thematic coding and analysis. The SAGE Encyclopedia of qualitative research methods 2008;868-869.

- Kindon S, Pain R, Kesby K. Participatory action research – origins, approaches and methods. In: Kondon S, Pain R, Mike K (eds). Participatory action research approaches and methods: connecting people, participation and place. 2008;9-18.

- Ayres L. Semi-structured interviews. The SAGE Encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. 2008;1(2):811-812.

- CDBRP. Coastal Rehabilitation and Mangrove Restoration using Melaleuca Fences: Practical Experience from Kien Giang province. 2011; Rach Gia: CDBRP.

- Nguyen TP, Parnell KE, Cottrell A. Human activities and coastal erosion on the Kien Giang coast, Vietnam. J Coast Conserv 2017;21(6):967–979.

- Pretty JN. Participatory learning for sustainable agriculture. Pergamon 1995;23(8):1247-1263.

- Vietnamese Prime Minister. The Program of Reinforcing and Upgrading the Sea Dyke System from Quang Ngai to Kien Giang provinces. 2009; Hanoi: Vietnamese Prime Minister.

- Vietnam Administration of Forestry. Report on assessment of management and uses of mangroves in the coasts of Southwestern Sea. Hanoi: Vietnam Administration of Forestry. 2012.

- Nguyen, Tan P, Luomb TT, Kevin EP. Mangrove Allocation for Coastal Protection and Livelihood Improvement in Kien Giang Province, Vietnam: Constraints and Recommendations. Land Use Policy 2017;63:401-407.

Citation: Luom TT (2019) Aquaculture Operation in Allocated Mangrove Areas in Kien Giang, Vietnam: Local Perceptions and Recommendations. J Coast Zone Manag 22:2.470

Copyright: © 2019 Luom TT. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.