Indexed In

- Online Access to Research in the Environment (OARE)

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- JournalTOCs

- Scimago

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- Access to Global Online Research in Agriculture (AGORA)

- Electronic Journals Library

- Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI)

- RefSeek

- Directory of Research Journal Indexing (DRJI)

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Scholarsteer

- SWB online catalog

- Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Publons

- MIAR

- University Grants Commission

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2020) Volume 11, Issue 6

Analyzing Livelihood Sustainability of Climate Vulnerable Fishers: Insight from Bangladesh

Atiqur Rahman Sunny1*, Kazi Mohammad Masum2, Nusrat Islam2, Mizanur Rahman3, Arifur Rahman4, Jahurul Islam5, Saidur Rahman6, Khandaker Jafor Ahmed7 and Shamsul Haque Prodhan12Department of Forestry and Environmental Science, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Bangladesh

3Department of Food Engineering and Tea Technology, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Bangladesh

4Department of Fisheries Biology and Genetics, Patuakhali Science and Bangladesh Technology University, Bangladesh

5Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS), Bangladesh

6The World Fish Center, Kishorganj, Bangladesh

7Department of Geography, The University of Adelaide, Australia

Received: 20-Dec-2019 Published: 20-Jun-2020, DOI: 10.35248/2155-9546.19.10.593

Abstract

Fish and fishery resources play an important role in improving socio-economic status of the fishing communities. Sylhet, the haor (bowl or saucer shape shallow depression) dominated administrative divisions (encompassing RAMSAR site and Ecological Critical Wetland Area) of Bangladesh is very promising for freshwater capture fisheries. But very few studies focused on the overall status on livelihood sustainability of fishing communities in this region. This study identified the demography, livelihood strategy, constraints of fishing and their coping strategies, strength, weakness and opportunity of fishing communities using household questionnaires, oral history interviews, and focus group discussions in Sylhet division (north eastern region of Bangladesh). The study identified physical strength and intention to work all the year round as the key strengths and acute poverty, poor economy, lack of alternative income generating opportunity and reduced fish availability as common weakness of fishers. Major threats facing by the fishers were natural calamities, overexploitation, dependency on natural resources and improper policy implication. Scope of alternative income generating opportunities, training and motivational program among the resource users and community based fisheries management could improve the situation. Findings of this study would provide important guideline for wetland management, planning and development of livelihood sustainability of the fishing communities.

Keywords

Fishing community; Livelihood Sustainability; Vulnerability; Biodiversity; Bangladesh

Introduction

Bangladesh is located on the world’s largest river deltas, created by the Ganges, the Brahmaputra, the Meghna and their tributaries. This is a riverine country of Southeast Asian region [1,2] having a total area of 147,570 km2 and a population of about 140 million [3]. The whole country is criss-crossed by 230 rivers and their tributaries and vast floodplain; thus ten percent of the total area of Bangladesh is always covered with water [4,5]. Bangladesh is the 4th largest producer of inland fisheries and has a huge water resource all over the country in the form of ponds, ditches, lakes, canals, small and large rivers and estuaries covering about 4.34 million hectares [6]. The favorable geographic position has blessed Bangladesh with a large number of aquatic species and provides plenty of resources to support fisheries potential [7]. It is enriched with freshwater fish species comprising 260 indigenous, 12 exotic, 24 freshwater prawn species [8,9].

Fish is the second most important agricultural crop in Bangladesh and its production contributes to the livelihoods and employment of millions of people [10,11]. The production and consumption of fish therefore has important implications for national income and food security. Bangladeshi people are also popularly referred to as “Mache BhateBangali” or “fish and rice makes a Bengali” [6]. Among all the division north eastern region (Sylhet division) is very promising for freshwater fishing due to abundance of wetlands of international importance [2,6]. Haor is a mosaic of wetlands including rivers, streams, irrigation canals and large area of seasonally flooded cultivated plains. There are 411 haors in Bangladesh comprising an area of about 8000 km2 [12]. Sylhet basin cover the most ecologically and economically important wetlands of Hakalukihaor (country’s largest haor), Tanguarhaor (RAMSAR site since 2000, country’s ecologically critical area 1999), Dekharhaor, Hail haor and Sanirhaor associated with Eralibeel and Jamaikatabeel. These haor occupies a land area of 40,000 ha area of three big districts (Sunamgonj, Moulvibazar, Sylhet) of Sylhet division. These Wetlands play vital role in the country’s economic, industrial, ecological, socio-economic, and cultural context [13-15]. It support the biodiversity of flora and fauna and contribute to build a sustainable socioeconomic life of millions of people of rural Bangladesh [14,16] by providing employment opportunities, irrigation, food and nutrition, fuel, fodder and transportation.

But the fish production from the fresh waters has declined to less than 40% [17] which gave a significant impact on the fishing community, their income, basic needs and overall socio-economic status. Fishermen community is deemed to be one of the most vulnerable communities in terms of their livelihood opportunities due to the deprivation of many amenities that considered them as the poorest of the poor [1,18-20]. It is important to understand the livelihood characteristics for sustainable development of Fish and fishery resources play an important role in improving socioeconomic conditions of the fishing community. Several studies were conducted on the socioeconomic condition of fishers of different districts in traditional method but very few systematic studies were conducted on the fishing community of north eastern region [1,16,18-20]. Thus the study was conducted using Sustainable Livelihood Approach (SLA) framework to gain knowledge about the livelihood strategy, strength, weakness, opportunity and threats of fishing communities of this region.

Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA)

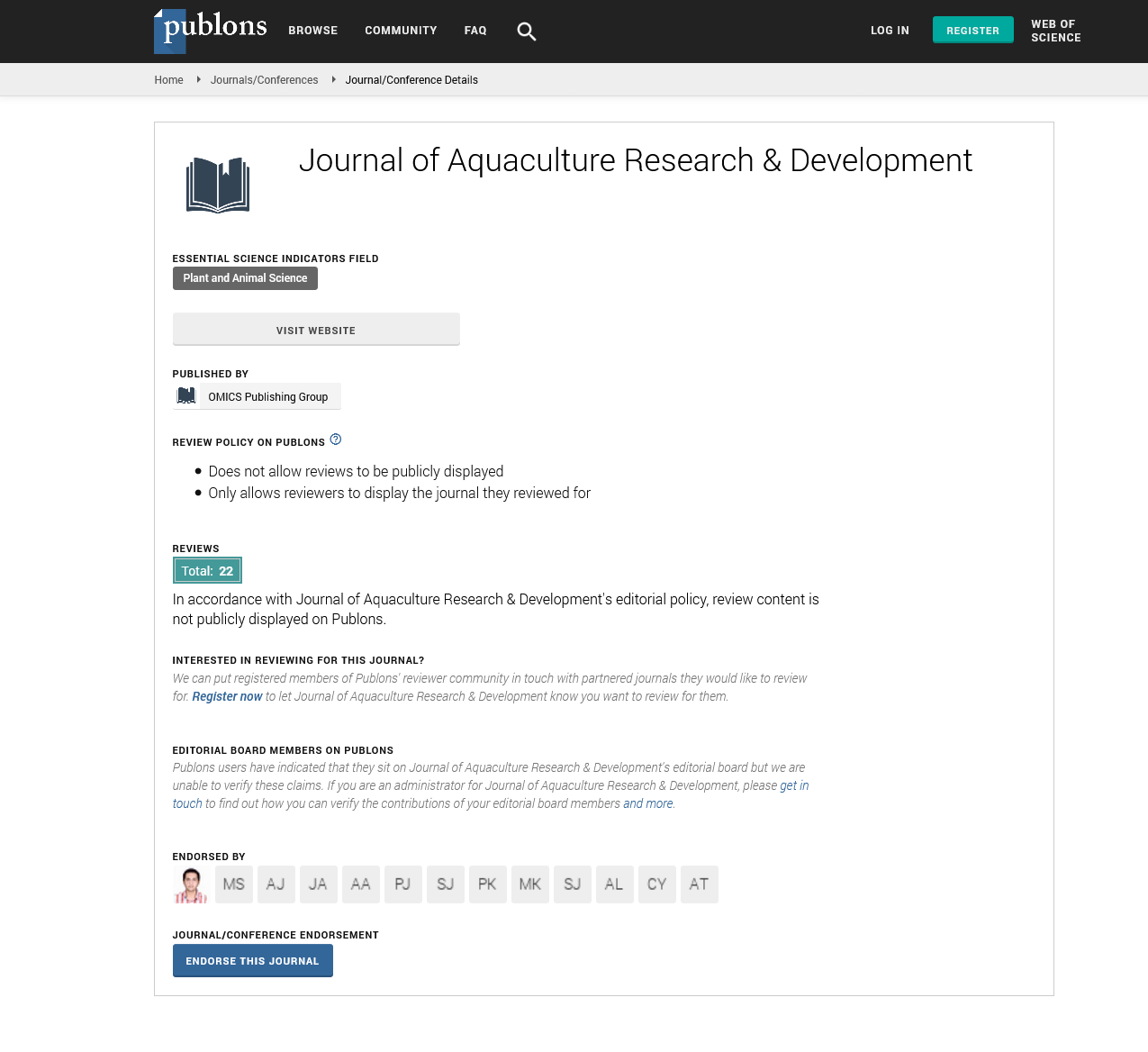

Livelihood means the capabilities, assets, resources and activities those are needed for living [21]. Livelihood become sustainable when it can be able to cope with and overcome stresses, shocks, and maintains capabilities and assets for present and future generation [22]. The Sustainable Livelihood Approach (SLA) provides an understanding of the lives of marginalized people by offering a way of poverty reduction [23]. There are five important key indicators for assessing sustainable livelihoods, these are natural (timber and non-timber forest resources, water, wildlife), physical (shelter, infrastructure, equipment), and financial capital as well as intangible human (education, skills, health) and social (institutions, relationships, trust) resources [24-28].

Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA) is important for development programs that aim to reduce poverty and vulnerability in communities who are engaged in small-scale fisheries and aquaculture [29,30]. The sustainable livelihoods framework helps to think and identify that poor might be very vulnerable to the assets and resources that assist them to survive, and the policies and institutions that put impact on their livelihoods [22]. Figure 1 shows the sustainable livelihoods framework and its various factors, which reduce or enhance livelihood opportunities and show their interrelation. Livelihood strategies include fisheries and agricultural intensification and expansion, livelihood diversification, and migration [24]. Institution and vulnerability are integral components of the SLA, and provide the crucial context where resources and strategies can be deployed and implemented.

Figure 1: The sustainable livelihoods framework [22].

Materials and Methods

Study sites

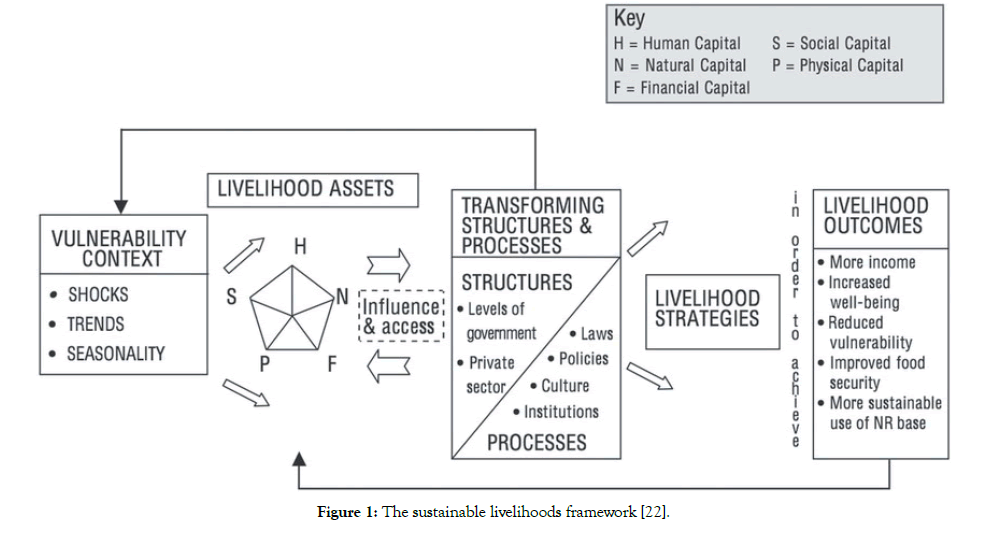

The study was conducted in five fishing communities of Sylhet division. The communities were selected considering the dependency on natural resources and socioeconomic structure. The communities were Dakkhinsreepur, Uttorsreepur of Tanguar Haor (ecologically critical area since 1999 and Ramsar site since, 2000) of Tahirpur Upazilla, and Uttorgaon, Dakkhingaon of Dekhar Haor of Sunamaganj Sadar Upazilla under Sunamganj District. For primary data collection, a number of qualitative tools such as individual interviews (II), focus group discussions (FGD) with various groups of stakeholders, key informant interview (KII) with knowledgeable persons and oral history were employed (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Location of the study areas.

Data collection

To collect empirical data, ‘household survey’ and ‘survey during fishing’ was conducted and a number of qualitative tools such as interviews, focus group discussions, and oral history were employed. Secondary data was collected from several sources including different articles, reports of freshwater wetlands, local and International newspapers. For analysis of qualitative data, content analysis method was employed; themes were identified and classified into manageable categories of different variables, such as natural capital, social capital, strength, opportunities, weakness, threats etc.

Questionnaire interviews

Using a semi-structured questionnaire exploratory interviews (total= 125) were conducted in five areas to collect necessary information. Each interview took approximately 50 minutes to complete. In addition to the 90 interviews above, ten FGD sessions with resource users (where each group consisted of 8–10 persons) were conducted. Finally, fifteen KII or cross-check interviews with local entrepreneurs, NGO personnel working on mangrove issues and forest officials were conducted to collect and verify or necessary information. Fishermen and community people were interviewed on boat, bank of the beel and haor, fishers’ houses, fish markets, paddy field and where participants could sit and feel comfortable.

Results

Socioeconomic status of fishers

Nuclear (72.9%) and joint families (27.1%) were present in the study areas. Size of the family was 4-7 persons in nuclear families and 8-12 persons in joint families and main profession was fishing. Among all the fishers 32% people were found engaged in fishing at the age group of 31-40 years, 22% people were in 41-50 years, 24% people were below 20 years, 22% people were between 21 to 30 years. Education is very important in socioeconomic aspects. Among the respondents of fishing communities 45% were illiterate, 30% can only sign their name, 15% got primary level education, 10% went to secondary level and no one went to higher secondary level. The income of the fishers was very poor. The only source of income of fishermen was selling fish in the market and other place. There were very limited options for non-fishery activities such as day labor activities in Agricultural field. Fishers got wages from 100 BDT (1.3 US$) to 180 BDT (2.3 US$) daily depending on their capability in Sylhet region. Alternative income generating activities are must for living standard improvement of the community people. Moreover, every year many people are leaving fishing profession getting involved in other profession due to increasing fishing pressure and climate change. Among the respondents 38% got assistance from the government and different private voluntary organizations during natural calamities especially flood. Most of the respondents (72%) had credit facility from NGOs. They didn’t have access to take bank loan as they didn’t have enough wealth to morgue in the bank (Table 1).

Table 1: Socioeconomic profile of fishers in the study area.

| Variables | Status | Mean (± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Family type | Nuclear | 72.9% |

| Joint | 27.1% | |

| Family size (in number) | Nuclear 4 to 7 | 5 (1.4) |

| Joint 8 to 12 | 10 (2.3) | |

| Age of fishers | <30 | 24% (5.9) |

| 21 to 30 | 22% (2.6) | |

| 30 to 40 | 32% (4.9) | |

| 40 to 50 | 22% (4.5) | |

| Education | Illiterate | 45% |

| Signed | 30% | |

| 0 to 5 | 15% | |

| 5 to 10 | 10% | |

| Occupation | Fishing | 94.9% |

| Other | 5.1% | |

| Income | Net annual income | 52,280 (1510) BDT |

| Access of alternative income | Yes | 51% |

| No | 49% | |

| Public/private assistance | Yes | 38% |

| No | 62% | |

| Access to credit | Yes | 72% |

| No | 28% |

People of this community become poorer and poorer due to debt cycle and intensive pressure of NGO’s credit. As natural calamities like flood, storm etc. is now a common phenomenon that badly hampers the income of the fishers especially who is dependent on only fishing profession. So, alternative income generating activities should be created and ensured. Income source should be diversified and engagement of women in income generating activities by maintaining the norms of their own society. Following suggested AIGAs (Alternative Income Generating Activities) could be helpful in this regards (Table 2).

Table 2: Potential AIGAs for men and women of fishing households.

| Name of potential AIGA | Rank | Target group | Justification | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Mechanic | 1 | Men | Who completed primary education |

|

| Auto mobile mechanic | 1 | Men | Part time/full time (Age 15 to 40) |

|

|

||||

| Tea stall | 2 | Men | Part time/during less availability (Age>40) |

|

|

||||

| Cage culture in open water | 2 | Men | Part time/during less availability (Age>40) |

|

|

||||

| Agriculture (Crop cultivation in land) | 1 | Men | Part time/during less availability (Age>40) |

|

|

||||

| Aquaponics (Integrated culture of fish and vegetables in homestead area) | 1 | Men | Part time/during less availability (Age>40) |

|

|

||||

| Poultry farm | 1 | Men | Part time/during less availability (Age>40) |

|

|

||||

| Small business | 2 | Men | Part time/during less availability (Age>40) |

|

| Rickshaw pulling | 1 | Men | Part time/during less availability (Age>40) |

|

| Sewing (Nakshikatha) | 1 | Women | Age 15 to 40 |

|

| Baby toys (made by cloth, clay, paper etc.) | 1 | Women | Age 15 to 40 |

|

|

||||

| Handy craft (made by bamboo, cloth etc.) | 1 | Women | Age 15 to 40 |

|

|

||||

| Hen/duck rearing (indigenous) | 1 | Women | Age>40 |

|

|

||||

| Vegetable cultivation in yard | 1 | Women | Age>40 |

|

| Fish pot mending | 2 | Women | Age>40 |

|

|

||||

| Net mending | 2` | Women | House wife and children |

|

|

Livelihood assets of fishing communities

Sustainable livelihoods approach (SLA) discuss with five types of capital upon which fishermen’s livelihood depend, categorized as human, natural, financial, social and physical capital.

Human capital

Human capital includes the knowledge, skills, working ability and good health of fishers. Fishing was done by using indigenous technology and fishers built up skills through their own knowledge. People were engaged in income generating activities like fishing, fish marketing, agriculture, homestead gardening and poultry rearing. Risk of contagious disease like diarrhea, typhoid and jaundice was found a common phenomenon due to inundation and flood when the locality suffers from lack/no sanitation facility. Decreased in fish catch due to seasonality, unavailability and overexploitation is responsible for malnutrition of this community. Fluctuation of temperature and rainfall and frequent occurrences of natural calamities reduce working capacity.

Natural capital

Natural capital of this region includes land, water, wild fry, fish and minerals. Environmental goods are critical in fish production. Fishers relied on rainfall, and sometimes canal water for fish availability and fishing. List of available fish species collected from local community is given below (Table 3).

Table 3: List of different fish species with their order name, local name, and scientific name.

| S. No. | Order | Scientific identity of the taxon with author | Vernacular or local Bengaliname | Common English name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Anguilliformes | Anguilla bengalensis (Gray, 1831) | Bamos | Indian mottled eel |

| 2. | Cypriniformes | Salmostomaphulo(Hamilton, 1822) | Fulchela | Flying barb |

| 3. | Cypriniformes | Esomusdanrica (Hamilton, 1822) | Darkina | Flying barb |

| 4. | Cypriniformes | Rasborarasbora (Hamilton, 1822) | Darkina | Flying barb |

| 5. | Cypriniformes | Chela labuca (Hamilton, 1822) | Labuca | Hatchet fish |

| 6. | Cypriniformes | Psilorhynchussucatio (Hamilton, 1822) | Titari | River stone carp |

| 7. | Cypriniformes | Bengalaelanga (Hamilton, 1822) | Sephatia | Bengala barb |

| 8. | Cypriniformes | Bariliusbendelisis (Hamilton, 1807) | Joia | Hamilton’s barila |

| 9. | Cypriniformes | Danio rerio (Hamilton, 1822) | Anju | Zebra danio |

| 10. | Cypriniformes | Osteobramacotio (Hamilton, 1822) | Dhela | Cotio |

| 11. | Cypriniformes | Systomussarana (Hamilton, 1822) | Sarpunti | Olive barb |

| 12. | Cypriniformes | Puntius chola (Hamilton, 1822) | Chalapunti | Chola barb |

| 13. | Cypriniformes | Pethiaguganio (Hamilton, 1822) | Molapunti | Glass-barb |

| 14. | Cypriniformes | Puntius conchonius (Hamilton, 1822) | Kanchanpunti | Rosy barb |

| 15. | Cypriniformes | Puntius ticto (Hamilton, 1822) | Tit punti | Ticto barb |

| 16. | Cypriniformes | Puntius sophore (Hamilton, 1822) | Jatpunti | Pool barb |

| 17. | Cypriniformes | Puntius terio (Hamilton, 1822) | Teri punti | One spot barb |

| 18. | Cypriniformes | Oreichthyscosuatis (Hamilton, 1822) | Kosuati | Sortfinner barb |

| 19. | Cypriniformes | Garra gotyla (Gray, 1830) | Gharpoia | Sucker head, Gotyla |

| 20. | Cypriniformes | Acanthocobitiszonalternans (Blyth, 1860) | Bilturi | River loaches |

| 21. | Cypriniformes | Schisturacorica (Hamilton, 1822) | Koikra | Stone loach |

| 22. | Cypriniformes | Schisturascaturigina (McClelland, 1839) | Dari | Stone loach |

| 23. | Cypriniformes | Schisturabeavani (Gunther, 1868) | Shavonkhokra | Greek loach |

| 24. | Cypriniformes | Somileptesgongota (Hamilton, 1822) | Poia | Gongota loach |

| 25. | Cypriniformes | Botiadario (Hamilton, 1822) | Rani | Stripped loach |

| 26. | Cypriniformes | Lepidocephalusguntea (Hamilton, 1822) | Gutum | Guntea loach |

| 27. | Cypriniformes | Labeorohita (Hamilton, 1822) | Rui | Rohu |

| 28. | Cypriniformes | Catlacatla (Hamilton, 1822) | Catla | Catla |

| 29. | Cypriniformes | Cirrhinuscirrhosus (Bloch, 1795) | Mrigal | Mrigal carp |

| 30. | Cypriniformes | Labeocalbasu (Hamilton, 1822) | Kala Baush | Karnataka labeo |

| 31. | Cypriniformes | Labeobata (Hamilton, 1822) | Bata | Bata labeo |

| 32. | Cypriniformes | Chaguniuschagunio (Hamilton, 1822) | Jarua | Minor carp |

| 33. | Cypriniformes | Labeoangra (Hamilton, 1822) | Angrot/kharas | Angralabeo |

| 34. | Cypriniformes | Labeogonius (Hamilton, 1822) | Ghainna | Kuria labeo |

| 35. | Cypriniformes | Labeonandina (Hamilton, 1822) | Nandina | Nandi labeo |

| 36. | Cypriniformes | Labeopangusia (Hamilton, 1822) | Ghoramach | Pangusialabeo |

| 37. | Cypriniformes | Cirrhinusreba (Hamilton, 1822) | Bhagna | Reba carp |

| 38. | Cypriniformes | Amblypharyngodonmola (Hamilton, 1822) | Mola | Molacarplet |

| 39. | Cypriniformes | Danio devario (Hamilton, 1822) | Debari | Bengal danio |

| 40. | Cypriniformes | Raiamas bola (Hamilton, 1822) | Bhol | Trout barb, Indian trout |

| 41. | Siluriformes | Eutropiichthysvacha(Hamilton, 1822) | Bacha, Bhacha | Schilbi |

| 42. | Siluriformes | Clariasbatrachus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Magur | Walking catfish |

| 43. | Siluriformes | Wallago attu (Bloch & Schneider, 1801) | Boal | Freshwater shark |

| 44. | Siluriformes | Heteropneustesfossilis (Bloch, 1794) | Shing | Stinging catfish |

| 45. | Siluriformes | Pangasiuspangasius (Hamilton, 1822) | Pangus | Pangas catfish |

| 46. | Siluriformes | Ailiacoila (Hamilton, 1822) | Kajuli | Gangetic catfish |

| 47. | Siluriformes | Rita rita (Hamilton, 1822) | Rita | Rita, Striped catfish |

| 48. | Siluriformes | Sperataaor (Hamilton, 1822) | Ayre | Long-whiskered catfish |

| 49. | Siluriformes | Mystuscavasius (Hamilton, 1822) | GolshaTengra | Gangetic mystus |

| 50. | Siluriformes | Mystusbleekeri (Day, 1877) | Tengra | Catfish |

| 51. | Siluriformes | Mystustengara(Hamilton, 1822) | BazariTengra | Stripped dwarf catfish |

| 52. | Siluriformes | Clupisomagarua (Hamilton, 1822) | Garua | River catfish |

| 53. | Tetraodontifomes | Tetraodon cutcutia (Hamilton, 1822) | Potka | Ocellated pufferfish |

| 54. | Beloniformes | Xenentodoncancila (Hamilton, 1822) | Kakila | Freshwater garfish |

| 55. | Beloniformes | Hyporhamphuslimbatus (Valenciennes, 1847) | Ekthota | Congaturi Halfbeak |

| 56. | Cyprinodontiformes | Aplocheiluspanchax (Hamilton, 1822) | Kanpona | Blue Panchax |

| 57. | Channiformes | Channastriatus (Bloch, 1793) | Shol | Snakehead murrel |

| 58. | Channiformes | Channamarulius (Hamilton, 1822) | Gajar | Giant snakehead |

| 59. | Channiformes | Channabarca (Hamilton, 1822) | Piplashol | Barca snakehead |

| 60. | Channiformes | Channa punctatus (Bloch, 1793) | Taki | Spotted snakehead |

| 61. | Channiformes | Channaorientalis(Bloch & Schneider, 1801) | Raga/Cheng | Walking snakehead |

| 62. | Clupiformes | Chitalachitala (Hamilton, 1822) | Chital | Clown knifefish |

| 63. | Clupiformes | Notopterusnotopterus (Pallas, 1769) | Foli | Bronze featherback |

| 64. | Clupiformes | Coricasoborna (Hamilton, 1822) | Kachki | The Ganges River Sprat |

| 65. | Perciformes | Macrognathusaculeatus (Bloch, 1786) | Tara baim | Lesser spiny eel |

| 66. | Perciformes | Mastacembelusarmatus (Lacepede, 1800) | Baim | Spiny eel |

| 67. | Perciformes | Mastacembeluspancalus (Hamilton, 1822) | Guchibaim | Spiny eel |

| 68. | Perciformes | Colisafasciatu(Bloch & Schneider, 1801) | Khalisha | Banded gourami |

| 69. | Perciformes | Colisalalia(Hamilton, 1822) | Lalkholisha | Dwarf gourami |

| 70. | Perciformes | Anabas testudineus (Bloch, 1792) | Koi | Climbing perch |

| 71. | Perciformes | Chanda nama Hamilton, 1822 | NamaChanda | Elongate Glass Perchlet |

| 72. | Perciformes | Parambassislala (Hamilton, 1822) | LalChanda | Highfin Glassy Perchlet |

| 73. | Perciformes | Parambassisranga (Hamilton, 1822) | Rangachanda | Indian glassy fish |

| 74. | Perciformes | Chanda beculis (Hamilton, 1822) | Chanda | Himalayan glassy perchlet |

| 75. | Perciformes | Glossogobiusgiuris (Hamilton, 1822) | Bele | Freshwater goby |

Financial capital

Financial capital includes fishers’ incomes, savings and credit. Fishers spent their income mostly for payment of loan, dowry payments and buying of fishing utensils like fishing net, boat etc. Farmers had very little scope to collect loan from Bank due to their ignorance and complex banking system. NGO activities were rampant in these areas. Due to lack of education, fishers went to money lenders and pay high interest rate of 10% monthly.

Physical capital

House, fishing gear, boat Vehicle, road, communication system, market, electricity, water supply, sanitary and health facilities were the physical capital of the fishing community. A totalof 14 types of fishing gear belonging 7 categories like koiajal, current jai, patijal, berjal, moiyajal, dubajal, tuna jal, kunijal, thelajal, chip/borshi, teta, koach, anta, chai were found in this region (Table 4).

Table 4: Different types of fishing gears used by the fishers.

| S. No. | Category | Type | Length (m) | Width (m) | Mesh size (cm) | Operating manpower |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gill net | Koiajal (Specialized net for Anabas testudineus | 50-65 | 1-1.5 | 0.5-1 | 1-2 |

| 2 | Gill net | Current jal (monofilament gill net) | 105-110 | 1.2-1.5 | 1-1.5 | 1-3 |

| 3 | Gill net | Patijal | 80-90 | 1.5-2 | 2.5-4 | 1-3 |

| 4 | Seine net | Tunajal | 7-8 | 3.5-5 | 0.5-1.2 | 5-10 |

| 5 | Seine net | Dubajal | 100-150 | 25-35 | 0.5-0.8 | 4-10 |

| 6 | Seine net | Moiajal | 5-7.5 | 4-4.5 | 0.3-0.4 | 4-10 |

| 7 | Seine net | Berjal | 100-220 | 2-3 | 0-0.5 | 5-10 |

| 8 | Cast net | Kunijal | - | - | - | 1 |

| 9 | Push net | Thelajal | - | - | - | 1 |

| 10 | Hook and line | Borshi | - | - | - | 1 |

| 11 | Spears | Teta | - | - | - | 1 |

| 12 | Traps | Chai | - | - | - | 1-2 |

Road and transportation service was very poor with severe health and sanitary problems. People got poor medical facilities due to long distance of the upazila hospital, scarcity of necessary pathological test and inactiveness of the community clinic system and people often suffered from diarrhea, cholera and malnutrition. Almost all households used tube-wells for drinking water. Electricity status of the communities was very poor and only 15% of farmers had electricity.

Social capital

Social capital includes relationship, cultural norms and other social factors that significantly help in exchanging experiences, sharing of knowledge and cooperation among rural communities. Fishers and their neighbors didn’t get any training so they contribute to the livelihood of each other by their own ideas of indigenous knowledge.

Vulnerabilities

Vulnerability deals with different strategies like shocks (unexpected events), trends (factors influence financially), seasonality (seasonal fluctuation of available resources), (Table 5) institutional structure and process that were composed of a range of activities and could vary from individual to individual or from household to household.

Table 5: Vulnerabilities of fishing communities.

| Shocks | Trends | Seasonality |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

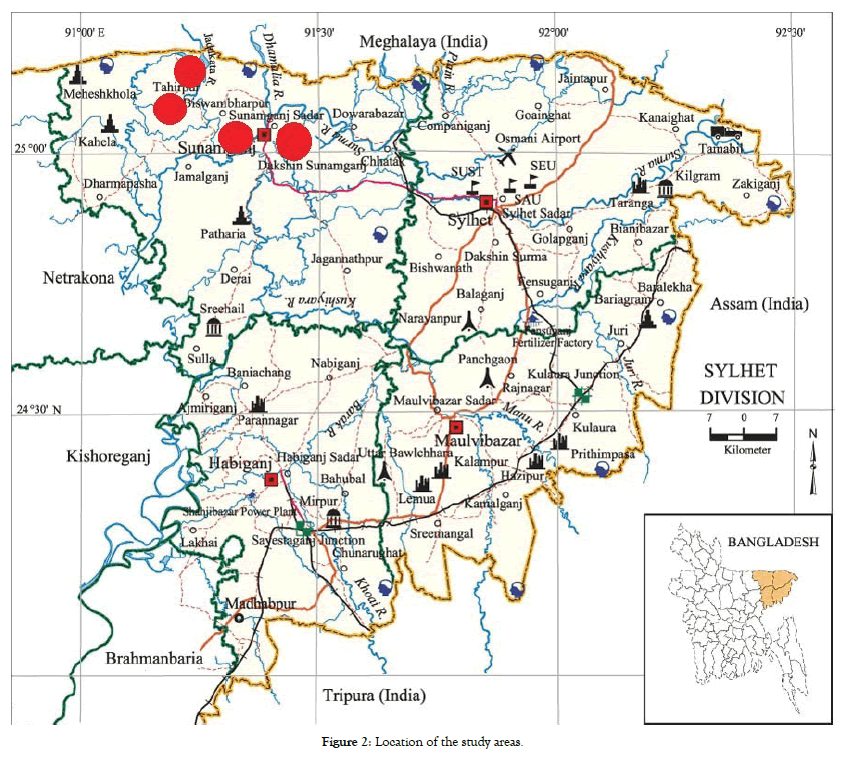

Institutional processes and livelihood outcomes

Understanding institutional processes help to identify the opportunities and barriers to sustainable livelihoods. Livelihood strategies and livelihood outcomes are influenced by transforming structures and institutional processes. The study found several transforming structures and processes that could be helpful for desirable outcomes from the fish production, harvesting and other economic activities of the fishing community. It was found livelihood outcome of the fishers depended simultaneously on livelihood assets, vulnerabilities and performance of institutions and organizations (Figure 3). Poor fishers had limited resources to maintain their livelihood. Government agencies, NGOs and the private sector could play significant role in this regards to improve the livelihood of the fishing communities. Introduction of public private partnership system for creating employment opportunities can improve the situation which will also encourage some entrepreneurs to small business as well as open the door of alternative income generating activities (AIGA).

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of livelihood outcomes of fishers.

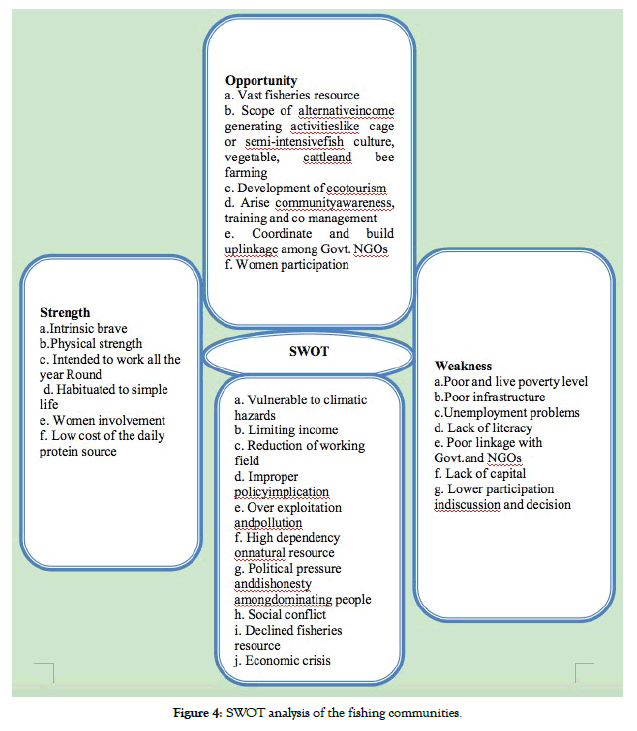

Strength, weakness, opportunity and threat

This study identified the Strength, weakness, opportunity and threat of the fishers from their livelihood approach and represents these by SWOT analysis (Figure 4). Intrinsic brave, physical strength, hardworking capacity, simple life style, protein availability and women involvement in economic activities were strengths of the fishing community. Weaknesses included acute poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, poor infrastructure and linkage with public and private organization, lack of capital and lower participation in the decision making. Vast water resources, Scope of AIGAs, ecotourism, awareness rising through co-management practice were the opportunities for the fishing communities to develop their livelihood in sustainable way. Fishers are facing some threats that included frequent occurrence of natural calamities, over exploitation, high dependency on natural resources, poor income, political pressure and improper policy implication. A summary of the key strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats with respect to the sustainable livelihood framework is given below (Figure 4).

Figure 4: SWOT analysis of the fishing communities.

Discussion

Fishers are the key protein supplier to the consumer though they are still deprived of basic needs and other professional facilities [1]. Sustainable livelihoods approach (SLA) can be helpful to find out the existing status of fishers and fisheries resource [31]. Fishers require various assets to achieve positive livelihood outcomes [24]. Capitals like knowledge, skills, working ability and good health enable fishers to pursue their livelihood strategies and achieve their livelihood objectives [22]. Changes in food availability and affordability due to natural calamities and seasonality add an additional burden to the health and income of the community [31]. Rapid population growth in fishing communities accelerated natural capital depletion that affected fish production and fishing. Changes in the availability of fish (natural capital) could affect total profit and harvesting costs, resulting in greater costs in managing and accessing natural capital [31]. Income of the wetland’s fishers in Bangladesh is not up to the mark. Low income hampers the savings and induces the credit taking tendency. Informal source of credit is only easily available to fishers with unfavorable interest, terms and condition [10,32-34]. Mahmud (2007) indicated fishers of Chalan beel (largest beel of north region) area had the highest income of 8000 BDT (196,000 BDT yearly) and Lowest 3000 BDT (36, 000 BDT yearly) [19] that support the finding of this study (yearly average income 52, 280 BDT). Reduction in income causes decreased in catches due to overexploitation, seasonality and climate change that induce malnutrition and under nutrition [35]. Climate change is also responsible for reduction of fish abundance and catches [36-38]. Income diversification could be the best option to increase the income of the fishers [20,39] and reduce over exploitation as well as high dependency on natural resources. Women could also contribute in family income [40]. Alternative income generating option could vary from place to place according to local demand, age, education, gender and capacity of the fishers.

Frequent occurrences of natural calamities destroy and hamper the productive assets and infrastructures [33,38,41-43]. This increased exposure to the hazard could also be attributed to inadequate structural protection, health facility, potable water, and sewage and drainage facility. Vulnerabilities of fishing community could also be influenced by different factors like shocks (diseases, floods and drought), trends (economic trends) and seasonality (seasonal fluctuation of fisheries resources) as well as social factors such as policies, institutions and process [2,44,45]. Existing livelihood status of a community could be understood easily by analyzing the strength, weakness, opportunities and threats of a community.

Internal factors are discussed via strengths and weakness, while threats and opportunities focus on external factors that affect the communities [18,46]. The process is a simple, qualitative analysis that encourages the development of opportunities to build strengths of the communities and overcome weaknesses while at the same time utilizing community’s strengths to minimize vulnerability to external threats [32,46]. The view that emerges from this SWOT analysis suggests training and motivational program should arrange to increase awareness among the resource users and improve their skill for sustainable use of natural resource that will ultimately change their living status. It is also helpful for the organizations who are involved in the development of such communities to carry out the activities of the organizations and for the consideration of their effective options.

Conclusion

Creation of alternative livelihood opportunity for fishers of north eastern region is vital for the current situation. Most of the families of this area are directly involved in fishing to maintain their livelihood throughout the year though the socioeconomic status of the fishers is not satisfactory due to social, economic and technical constraint. There is also lack sufficient baseline information to initiate proper developmental steps and to improve the livelihood of fishermen. Resource base data bank should be established for future research and development. Implementation of appropriate policies, legal instruments and introduction of comanagement strategies for wetland management could improve the situation of the fishing communities and fish production of the wetland. Community based fisheries management could also improve the situation with the help of different government organizations, NGOs, donor organization, research organization and other national and international organizations. The findings of the present study could become a guideline for planning and management of the wetlands and development of the livelihood of fishing communities.

REFERENCES

- Kamruzzaman M, Hakim MA. Livelihood status of fishing community of Dhaleshwaririver in central Bangladesh. International Journal of Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering. 2016; 2: 25-29.

- Sunny AR, Reza J, Anas M, Hassan MN, Baten MA, Hasan MR, et al. Biodiversity assemblages and conservation necessities of ecologically sensitive natural wetlands of north eastern Bangladesh. Indian Journal of Geo Marine Sciences. 2020.

- Kamal MM. Temporal and spatial variation in species diversity of fishes in the Karnafully River Estuary. M.Sc. Thesis, Institute of Marine Sciences, University of Chittagong, Bangladesh. 2020.

- Ali A. Livelihood and food security in Rural Bangladesh: The Role of Social Capital. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University. 2005.

- Rahman MJ, Wahab MA, Meisner CA. ECOFISHBD Project: A joint initiative of government-non-government donor for hilsa and other fisheries resources conservation, productivity improvement and strengthening fishers capacity, National Fish Week 2015 Compendium (In Bengali), Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock, Bangladesh. 2015; 116-118

- Ghose B. Fisheries and Aquaculture in Bangladesh: Challenges and Opportunities. Annals of Aquaculture and Research. 2014; 1: 1001.

- Shamsuzzaman MM, Islam MM, Tania NJ, Al-Mamun MA, Barman PP, Xu X. Fisheries resources of Bangladesh: Present status and future direction, Aquaculture and Fisheries. 2017.

- DoF. Compendium on Fish Fortnight 2005. Department of Fisheries, Matshya Bhaban, Park Avenue Ramna, Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2005; 109.

- DoF. Development project, Department of Fisheries, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2012.

- Islam MM, Islam N, Sunny AR, Jentoft S, Ullah MH, Sharifuzzaman SM. Fishers’ perceptions of the performance of hilsa shad (Tenualo sailisha) sanctuaries in Bangladesh, Ocean & Coastal Management; 2016; 130: 309-316.

- Sunny AR. A review on the effect of global climate change on seaweed and seagrass. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies. 2017; 5: 19-22.

- Pandit D, Kunda M, Harun-Al-Rashid A, Sufian MA, Mazumder SK. Present Status of Fish Biodiversity in Dekhar Haor, Bangladesh: A Case Study. World Journal of Fish and Marine Sciences. 2015.

- Islam SN, Gnauck A. Effects of salinity intrusion in mangrove wetlands ecosystems in the Sundarbans: an alternative approach for sustainable management. In: Okruszko T, Jerecka M, Kosinski K,eds. Wetlands: Monitoring Modelling and Management. Leiden: Taylor& Francis/Balkema, USA. 2007; 315–322.

- Ahmed I, Deaton BJ, Sarker R, Virani T. Wetland ownership and management in a common property resource setting: A case study of Hakaluki Haor of Bangladesh. Ecological Economics, Science Direct, 2008; 429-436.

- Islam MM, Sunny AR, Hossain MM, Friess DA. Drivers of mangrove ecosystem service change in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography. 2018; 39.

- Nishat A. Fresh water wetlands in Bangladesh: Status and issues. In: Nishat A, Hossain B, Roy M K, Karim A, eds. Freshwater Wetlands in Bangladesh—Issues and Approaches for Management. Dhaka: IUCN. 1993; 9–22.

- DoF. Fisheries resources information of Bangladesh. In: Islam, M.N. (ed.). Fish fortnight compendium. Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries and livestock. Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2002; 44-46.

- Hossain T. Study on biodiversity of fish fauna and socio economic condition of Kolimarhaor, Itna, Kishoreganj. M.S. Thesis, submitted to the Department of Fisheries Management, BAU, Mymensing. 2007; 38.

- Mahmud TA. Fish biodiversity and socio-economic conditions of the fishing community in some selected areas of Chalanbeel. M.S. Thesis submitted to the Depeartment of Aquaculture, BAU, Mymensingh. 2007; 27-53.

- Mohammed EY, Wahab MA. Direct economic incentives for sustainable fisheries management: the case of hilsa conservation in Bangladesh. International Institute for Environment and Development, London, England. 2013.

- Scoones I. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. The Journal of Peasant Studies. 2009; 36: 171-196.

- DFID. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. Department for International Development (DFID), London, UK. 1999.

- Agarwala M, Atkinson G, Fry BP, Homewood K, Mourato S, Rowcliffe JM, et al. Assessing the Relationship between Human Well-being and Ecosystem Services: A Review of Frameworks. Conservation and Society. 2014; 12: 437.

- Scoones I. Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis. IDS Working Paper 72, Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Brighton, UK. 1998.

- Fine B. The development state is dead: Long live social capital? Development and Change. 1999; 30: 1-19.

- Brocklesby MA, Fisher E. Community development in sustainable livelihoods approaches – an introduction. Community Development Journal. 2003; 38: 185-198.

- Stirrat RL. Yet another ‘magic bullet’: the case of social capital. Aquatic Resources, Culture and Development. 2004; 1: 25-33.

- Schreckenberg K, Camargo I, Withnall K, Corrigan C, Franks P, Roe D, et al., Social assessment of conservation initiatives: a review of rapid methodologies. London: IIED. 2010.

- Edwards P, Little D, Demaine H. Rural Aquaculture. CABI International, Wallingford, Oxford, UK. 2002; 358.

- Neiland AE, Bene C. Poverty and small-scale fisheries in West Africa. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nation, Rome, Italy. 2004.

- Badjeck MC, Allision HA, Halls AS, Dulvy NK. Impacts of climate variability and change on fishery-based livelihood. Marine policy. 2010; 34: 375-383.

- Stanton D, Foreman N, Wilson P. Uses of virtualreality in clinical training: Developing the spatial skillsof children with mobility impairments. In G. Riva, B. Wiederhold & E. Molinari (Eds.), Virtual reality in clinical psychology and neuroscience. 1998; 219–232.

- Tietze U, Villareal LV. Microfinance in fisheries and aquaculture. Guidelines and case studies. Rome: FAO. 2003.

- De Silva D, Yamao M. Effects of the tsunami on fisheries and coastal livelihood: a case study of tsunami-ravaged southern Sri Lanka. Disasters. 2007; 31: 386–404.

- Ogutu-Ohwayo R, Hecky RE, Cohen AS, Kaufman L. Human impacts on the African Great Lakes. Environmental Biology of Fishes. 1997; 50: 117–131.

- Mahon R. Adaptation of fisheries and fishing communities to the impacts of climate change in the CARICOM region: issue paper-draft. Mainstreaming adaptation to climate change (MACC) of the Caribbean Center for Climate Change (CCCC), Organization of American States, Washington, DC. 2002.

- Sunny AR, Islam MM, Nahiduzzaman M, Wahab MA. Coping with climate change impacts: The case of coastal fishing communities in upper Meghnahilsa sanctuary of Bangladesh. In: Babel MS, Haarstrick A, Ribbe L, Shinde V, Dichti N (Eds.), Water Security in Asia: Opportunities and Challenges in the Context of Climate Change, Springer. 2018.

- Islam MM, Islam N, Mostafiz M, Sunny AR, Keus HJ, Karim M, et al. Differences between livelihood and biodiversity conservation: A model study on gear selectivity for harvesting small indigenous fishes in southern Bangladesh, Zoology and Ecology. 2018.

- Sunny AR, Islam MM, Rahman M, Miah MY, Mostafiz M, Islam N, et al. Cost effective aquaponics for food security and income of farming households in coastal Bangladesh. The Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research. 2019.

- Gupta MV, Ahmed M, Bimbao B, Lightfoc C. Socioeconomic impact and farmers assessment of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromisniloticus) culture in Bangladesh. ICLAM, Makati, Metro, Malina, Philippines. 1992; 50.

- Iwasaki S, Razafindrable BH, Shaw R. Fishery livelihood and adaptation to climate change: a case study of chilika lagoon, India. Mitigation and adaptation strategies for global Change. 2009; 14: 339-355.

- Sunny AR, Hassan MN, Mahashin M, Nahiduzzaman M. Present status of hilsa shad (Tenualosailisha) in Bangladesh: A review. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies. 2017; 5: 2099-2105.

- Olago D, Marshall M, Wandiga SA, Opondo M, Yanda PZ, Kangalawe R, et al. Climatic, socioeconomic and health factors affecting human vulnerability to cholera in the lake Victoria basin, East Africa, AMBIO. 2007; 36: 350-358.

- Beatrice SM. Impacts of protected areas on local livelihood: a case study of saadani national park. Master’s thesis in Natural Resources Management (Biology), Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Natural Science and Technology. 2016.

- Sunny AR. Impact of oil Spill in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies. 2017; 5: 365-368.

- Cowx IG, Arlinghaus R, Cooke SJ. Harmonizing recreational fisheries and conservation objectives for aquatic biodiversity in inland waters. Journal of Fish Biology. 2010; 76: 2194–2215.

Citation: Sunny AR, Masum KM, Islam N, Rahman M, Rahman A, Islam J, et al. (2020) Analyzing Livelihood Sustainability of Climate Vulnerable Fishers: Insight from Bangladesh. J Aquac Res Development. 11: 6. doi: 10.35248/2155-9546.19.10.593

Copyright: © 2020 Sunny AR, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.