Indexed In

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Case Report - (2023) Volume 7, Issue 1

Abdominal Cocoon as a Rare Cause of Acute Intestinal Obstruction: A Case Report

Mohamed A. Hussein1, Tamer A. Abouelgreed2*, Tamer Saafan3, Ehab A. Diab4, Dena M. Abdelraouf5, Nermeen M. Abdelmonem6 and Tamer G. Abdelhamid72Department of Urology, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

3Department of General Surgery, NMC Royal hospital, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

4Department of Radiology, AlQasemi Hospital, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

5Department of Radiology, NMC Royal Hospital, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

6Department of Radiology, Thumbay University Hospital, Ajman, United Arab Emirates

7Department of Anesthesia, Emirates specialty Hospital, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Received: 18-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. JSA-23-19602; Editor assigned: 20-Jan-2023, Pre QC No. JSA-23-19602 (PQ); Reviewed: 03-Feb-2023, QC No. JSA-23-19602; Revised: 10-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. JSA-23-19602 (R); Published: 20-Feb-2023, DOI: 10.35248/2684-1606.23.07.195

Abstract

Abdominal cocoon is one of the rare causes of intestinal obstruction. It is referred as complete or partial small bowel encapsulation caused by the thick fibro collagenous membrane. It is most common in young adolescent girls. We present a 34-year-old male patient with idiopathic abdominal cocoon causing intestinal obstruction. Few cases of male patients suffering from idiopathic abdominal cocoon have been reported in literature.

Keywords

Abdominal cocoon; Subacute intestinal obstruction; Idiopathic abdominal cocoon; Multinucleated giant cells; Hernia

Abbreviations

CT: Computed Tomography Abdominal cocoons; ABS: Abdominal Cocoon Syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal cocoon is referred as a complete or partial small bowel encapsulation caused by dense fibro collagen membranes leading to acute or chronic small bowel obstruction. It was first termed as peritonitis chronic fibrosin capsulata by Owtschinnikow in 1907 and finally abdominal cocoon by Foo in 1978 [1]. It is most commonly seen in adolescent girls of tropical and subtropical region though few cases of male have also been reported in literature [1, 2].

Case Presentation

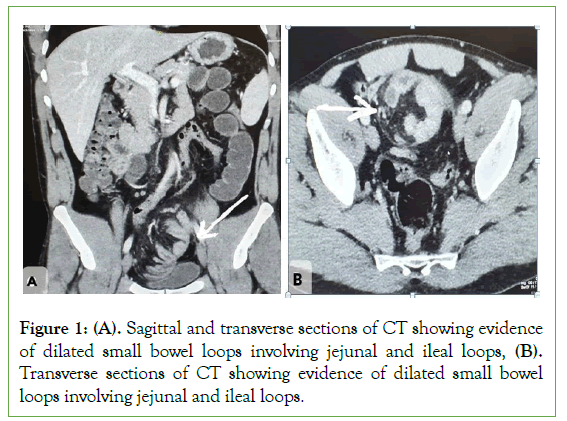

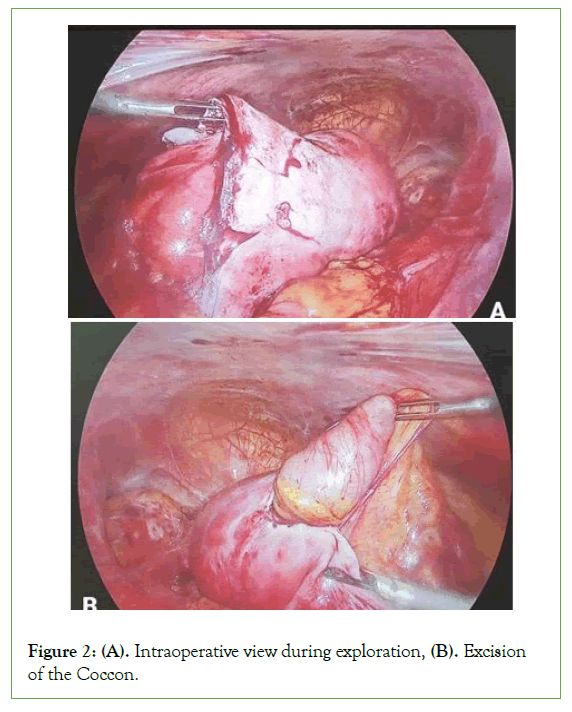

A 34-year-old male patient presented with acute abdominal pain, distension and recurrent vomiting for the last 2 days with signs of intestinal obstruction. The patient had a past history of recurrent abdominal pain during the last 2 months. There was no associated fever. On physical examination, there was tenderness over the right iliac fossa. The patient underwent Computed Tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis (plain and contrasted) which showed evidence of dilated small bowel loops involving jejunal and ileal loops apart from the distal few centimeters of ilium (Figure 1). The distal ileal loops is seen clustered within thin wall sac like structure in the lower abdomen with convergent, crowded and congested mesenteric vessels associated with minimal streaks of edema. The sigmoid colon is displaced medially and right supero-lateral surface of urinary bladder is compressed. Normal enhancement pattern of the bowel walls. The above finding is suggesting small bowel obstruction due to internal hernia likely of trans mesenteric type (Figure 2). Laparoscopic exploration of the whole abdomen was done; the internal herniated ileum was found encased in a cocoon- like fibrotic tissue with a diameter of nearly 15 cm. We cut the fibrous membrane and the small bowel loosened. Circulation of the bowel segment was intact. On the 3rd post-operative day the patient was discharged.

Figure 1: (A). Sagittal and transverse sections of CT showing evidence of dilated small bowel loops involving jejunal and ileal loops, (B). Transverse sections of CT showing evidence of dilated small bowel loops involving jejunal and ileal loops.

Figure 2: (A). Intraoperative view during exploration, (B). Excision of the Coccon.

Histopathology

Gross description: The specimen is identified as hernia sac and consists of 4 cystic like fragments together measuring 4.5 cm × 4.5 cm × 0.5 cm totally submitted in four cassettes.

Microscopic description: Sections examined show fibrous tissue infiltrated by plasma cells, multinucleated giant cells, plump activated fibroblasts with pale staining nuclei, histiocytes with small nuclei and abundant vacuolated cytoplasm, hemorrhage and granulation tissue with chronic inflammatory infiltrate.

Results and Discussion

Abdominal cocoon is one of the rare sicknesses causing acute to subacute intestinal obstruction. This is an unprecedented peritoneal sickness characterized through a dense, off-white, membranous layer of fibrous connective tissue that surrounds a few or all the stomach organs, such as a silkworm cocoon. Because of the shortage of specificity of clinical manifestations, it is difficult to distinguish from intestinal obstruction, perforation, or abdominal mass as a result of different reasons, so preoperative prognosis is tough, and the diagnosis specifically depends on intraoperative findings [3]. The prevalence of Abdominal Cocoon Syndrome (ACS) is unknown, but it occurs in 1.4%–7.3% of peritoneal dialysis patients [4]. Abdominal cocoons are more common in males, and the male to female ratio is about 1.2 to 2:1 [5]. The role of laparoscopy is limited to elective investigation and auxiliary diagnosis, but due to the nature of adhesions and bowel entrapment, open exploration is unintentionally required for treatment [6]. In our case, we performed diagnostic laparoscopy and completed the procedure without conversion to laparotomy. The patient underwent emergency surgery for intestinal obstruction, during which an abdominal callus was found. Abdominal cocoons are characterized by small bowel obstruction caused by all or part of the small bowel being covered by a dense fibrous membrane, also known as idiopathic sclerosing peritonitis, small bowel incarceration, and intestinal fibrous membrane prolapse [7]. The etiology of abdominal cocoon can be divided into primary abdominal cocoon and secondary abdominal cocoon. Primary abdominal cocoon disease is mainly caused by curling embryo body, abnormal differentiation of mesoderm, and dysplasia of dorsal intestinal mesentery. It is often associated with diseases such as loss of omentum, loss of gastrocolic ligament, bowel or colon malrotation, visceral displacement, cryptorchidism, and hernia [8]. The causes of secondary abdominal cocoon formation are as follows: (1) Changes in the abdominal microenvironment: abdominal and pelvic infections caused by various factors, history of abdominal surgery, long-term peritoneal dialysis, malignant tumors, etc. In addition to abdominal tuberculosis, autoimmune diseases, liver transplantation and other immune factors can cause abdominal cocoons [9]. In recent years, some clinicians have also observed abdominal injury and hepatitis C as etiologies [10]. There are also reports of abdominal cocoons with free abdominal gas [11]. (2) Drug effects: Chemotherapy drugs, B-receptor blockers, and mercury can cause peritonitis, leading to abdominal cocoon formation, accompanied by excessive collagen production and abdominal fibrosis [12]. Because the patient had a history of anemia in the past and no other diseases were found, the diagnosis was primary abdominal cocoon. Abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting, and large lumps are all symptoms of abdominal cocoon. The course of the disease varies in length. Preoperative diagnosis is challenging and most are based on intraoperative findings. According to Wei et al, The main clinical manifestations of 24 cases of abdominal cocoon were incomplete or complete intestinal obstruction (88%) and abdominal mass (54%) [13]. According to Machado et al. The most common clinical manifestations of abdominal cocoon are abdominal pain (72%), abdominal distension (44.9%), and abdominal mass (30.5%) [14]. There are few reports of abdominal cocoon with intestinal perforation. Preoperative gastrointestinal x-rays and high-resolution CT scans help to identify the presence of abdominal cocoons [15]. However, gastroenterography can exacerbate abdominal symptoms in patients with acute intestinal obstruction or perforation and should therefore be used with caution [16]. CT diagnosis requires high technical requirements for doctors; this patient underwent an abdominal CT scan and found abdominal cocoons; therefore, the diagnosis of abdominal cocoons mainly relies on the results of CT scans. The principle of operation is to remove the capsule, loosen adhesions, and relieve obstruction [16].

The surgical methods are as follows

Intestinal resection: suitable for cases of intestinal ischemic necrosis. In this case, due to intestinal necrosis, we removed part of the necrotic small intestine.

Bowel assembly: It is suitable for cases where the adhesion is firm and cannot be separated to eliminate the obstruction. In order to avoid excessive other injuries, such as postoperative intestinal fistula, necrosis and other complications, it is not advisable to cut too far to completely remove the capsule.

Appendectomy: It is suitable for patients who are found to have obvious appendix stones during the operation and may develop acute appendicitis in the future.

Conclusion

Intestinal obstruction caused by abdominal cocoon is rare. When we encounter patients with intestinal obstruction in clinical work, we must carefully inquire about their medical history. If the patient has no history of digestive system disease, the possibility of abdominal cocoon should be considered.

Declaration

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by first author institute. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

TA and MH designed this study, collected the information, images, and wrote the manuscript. ED and TS, reviewed the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Solak A, Solak I. Abdominal cocoon syndrome: Preoperative diagnostic criteria, good clinical outcome with medical treatment and review of the literature. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2012; 23(6):776-779.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oran E, Seyit H, Besleyici C, Unsal A, Alis H. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis as a late complication of peritoneal dialysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2015; 4(3):205-207.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Çolak S, Bektas H. Abdominal cocoon syndrome: A rare cause of acute abdomen syndrome. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2019; 25(6):575-579.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Solmaz A, Tokocin M, Arıcı S, Yiğitbaş H, Yavuz E, Gülçiçek OB, et al. Abdominal cocoon syndrome is a rare cause of mechanical intestinal obstructions: A report of two cases. Am J Case Rep. 2015; 16:77.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yavuz R, Akbulut S, Babur M, Demircan F. Intestinal obstruction due to idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: A case report. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015; 17(5).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar M, Deb M, Parshad R. Abdominal cocoon: Report of a case. Surg Today.2000; 30(10):950-953.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Azzawi M, Al-Alawi R. Idiopathic abdominal cocoon: A rare presentation of small bowel obstruction in a virgin abdomen. How much do we know?. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;bcr2017219918

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uzunoglu Y, Altintoprak F, Yalkin O, Gunduz Y, Cakmak G, Ozkan OV, et al. Rare etiology of mechanical intestinal obstruction: Abdominal cocoon syndrome. World J Clin Cases. 2014; 2(11):728.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaur S, Doley RP, Chabbhra M, Kapoor R, Wig J. Post trauma abdominal cocoon. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015; 7:64-65.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akbulut S, Yagmur Y, Babur M. Coexistence of abdominal cocoon, intestinal perforation and incarcerated Meckel’s diverticulum in an inguinal hernia: a troublesome condition. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2014; 6(3):51.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asotibe JC, Zargar P, Achebe I, Mba B, Kotwal V. Secondary abdominal cocoon syndrome due to chronic beta-blocker use. Cureus. 2020; 12(9).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li S, Wang JJ, Hu WX, Zhang MC, Liu XY, Li Y, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of 26 cases of abdominal cocoon world. J Surg. 2017; 41(5):1287-1294.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wei B, Wei HB, Guo WP, Zheng ZH, Huang Y. Hu BG, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of abdominal cocoon: A report of 24 cases. Am J Surg. 2009; 198(3):348-353.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Machado NO. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016; 16(2):e142-151.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gorsi U, Gupta P, Mandavdhare HS, Singh H, Dutta U, Sharma V. The use of computed tomography in the diagnosis of abdominal cocoon. Clin Imaging. 2018; 50:171-174.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh AU, Subedi SS, Yadav TN, Gautam S, Pandit N. Abdominal cocoon syndrome with military tuberculosis. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2021; 14(2):577-580.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Hussein MA, Abouelgreed TA, Saafan T, Diab EA, Abdelraouf DM, Abdelmonem NM et. al, (2023) Abdominal Cocoon as a Rare Cause of Acute Intestinal Obstruction: A Case Report. J Surg Anesth. 7:195.

Copyright: © 2023 Hussein MA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.