Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- JournalTOCs

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2023) Volume 14, Issue 2

A Prospective Study on Direct Out-of-Pocket Expenses of Hospitalized Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in a Philippine Tertiary Care Center

Fernandez Lenora* and Ang Blake WarrenReceived: 28-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. JCRB-23-20421 ; Editor assigned: 31-Mar-2023, Pre QC No. JCRB-23-20421 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Apr-2023, QC No. JCRB-23-20421 ; Revised: 21-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. JCRB-23-20421 (R); Published: 28-Apr-2023, DOI: 10.35248/2155-9627.23.14.458

Abstract

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a frequent cause of morbidity and mortality in the Philippines and majority of the economic burden lies in hospitalizations during an exacerbation. Despite coverage of hospitalization cost with the national health insurance system (Phil-Health) for COPD exacerbations, patients often pay out-of-pocket. This study aimed to determine the demographic characteristics of COPD admissions at a Philippine tertiary care center, Philippine General Hospital, and assess mean cost of hospitalization, and identify predictors of prolonged hospitalization and cost >20,000 Philippine pesos (Php). A prospective cross-sectional study was conducted for 6 months by chart review. Patients were categorized as charity service patients, that is, with no charged professional fees and free medications and private service patients who pay for their health care services. A total of 43 COPD admissions were included. The average daily cost of hospitalization (per 1,000 pesos) for service patients was at 4.25 compared to private service patients at 16. Demographic characteristics and type of accommodation were not significant, predictors of prolonged hospital stay nor hospitalization cost of >Php 20,000. Accommodation cost and professional fees accounted for majority of the overall cost for private patients, while medications and diagnostic tests were the major contributor to the overall cost for charity patients. Despite existence of Phil-health, in-patient coverage for COPD remains insufficient. Measures for maximizing COPD control in the out-patient setting could potentially reduce total cost for this disease.

Keywords

COPD; Exacerbations; Cost of hospitalization

Introduction

COPD is an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality in the Philippines. Estimates of the disease burden project COPD to be the third leading cause of mortality worldwide. Majority of the economic burden lies in the cost of hospitalizations during a COPD exacerbation [1-3]. With the new national health insurance structure, diseases are given specific case rates, and allows for faster disbursement of claims [4]. This however may cause greater out-of- pocket expenses by the patients [5]. The Based on local studies of the disease in the Philippines, the incidence of COPD is reported to be at least 14%, whereas in other Association of Southeast Asian Countries (ASEAN) countries, the reported incidence is only at 6%. Smoking is one of the implicated risk factors for disease development, and smoking in the Philippines is noted to be higher at 28.3% than its ASEAN counterparts. This translates to at least 17 million of smoking adult Filipinos [6-8].

Although multiple therapies are already available for COPD, the disease remains underdiagnosed and undertreated especially among primary care physicians [9-11]. Undertreated and uncontrolled COPD is marked by frequent exacerbations, defined as an acute event of worsening respiratory symptoms requiring medications. Markers for increased risk of exacerbations based on studies include old age, chronic mucus hypersecretion, and decreased FEV1. Moreover, COPD is progressive and end-stage disease is characterized by dyspnoea even at rest with eventual respiratory failure [12].

Important factors that influence the health care costs of COPD, in general, include disease severity, frequency of exacerbations, and the presence of comorbidities [6,13]. The predominant economic burden lies in the hospitalization costs for COPD exacerbations which are linked to higher mortality rates. In the US, exacerbations account for $18 billion in direct costs annually [6,14].This high cost of therapy appears universal based on several studies conducted in Asia [15-17]. Treatment must, therefore, focus on the control of symptoms and prevention of future exacerbations with emphasis on the use of maintenance inhaler therapies. This poses a problem among low-income countries like the Philippines, which utilizes health care resources to respond mainly to acute illnesses and is less adept at addressing chronic conditions, such as COPD [18].

National health coverage initially came into law through the Philippine Medical Care Act of 1969 and was eventually implemented in 1971. This act provided total coverage of medical services according to the needs of the patients. The passage of legislative House Bill 14225 and Senate Bill 01738 enabled the development of the National Health Insurance Act of 1995. This created the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (Phil Health) [19]. As of 2011, the case rate system was introduced where the payment mechanism sets pre-determined coverage for select medical conditions and surgical procedures [5].This significantly reduced the turnaround time or processing of claims since the amount of coverage is already identified. The new case rate system however may cause out-of-pocket expenses, with the present coverage for COPD set at only Php 12,200. This study aims to identify the amount of out-of-pocket expenses by patients admitted for COPD exacerbation at the Philippine General Hospital and predictors for prolonged stay and hospitalization costs [19]. This study aimed to determine the economic burden of COPD admissions in Philippine General Hospital, which is the largest national university hospital in the Philippines that caters to both private (paying) and charity (service) patients. Financial estimates on the direct costs of treatment for COPD exacerbations in excess to the case rate provided by Phil-Health insurance were likewise determined. This was a pilot study that will lead to the performance of a national-scale research project.

The objectives of this study were to determine the out-of-pocket expenses of adult patients admitted for COPD in acute exacerbation using direct costing. The general demographics of the confined COPD patients were gathered, the mean cost of hospitalization due to COPD exacerbation among private and charity patients were compared, the relationship between baseline demographic characteristics and costs was evaluated and the predictors of hospitalization cost and prolonged hospital stay of COPD in exacerbation were determined.

A prospective cross-sectional study was conducted for 6 months from the time of institutional ethics board approval by chart review. This study focused on out-of-pocket expenses of patients for hospitalization utilizing direct costing. A total enumeration of cases was employed for sample size.

Materials and Methods

The subjects included in this study were admissions from both charity and pay wards of adult patient’s ≥ 19 years old with the main diagnosis of COPD and Phil Health enrollment claims using the ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code J44.9. Patients who were ≤ 18 years old, not having COPD or ICD code J44.9 as being one of the primary assessments on admission and those who developed COPD exacerbation only during the hospital stay were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

All admissions fulfilling the inclusion criteria within the pre- set period was included in the study. Baseline characteristics, diagnostic and therapeutic sheets review was done. Recognizing the variability in terms of costing for medications that will be bought outside the institution, actual brand names used by each patient for their medicines have been recorded to allow for costing to be more accurately derived. For the diagnostic procedures, laboratory or imaging tests that were performed outside the institution were also recorded. Information was gathered directly from the nursing personnel/watchers caring for the patient. Direct costing for these medicines and procedures were inquired from patients/company or the actual establishments where these tests were bought or performed. Medications and diagnostic tests not indicated in the chart or not implemented or carried out were excluded as part of the direct costing. Other sources of direct costs such as syringes, IV lines, fluids, etc were not included in this study due to difficulty in accounting its use. Chart reviews were done regularly at 1-3- day intervals during the course of stay, noting daily changes in the medications, or new diagnostic procedures ordered. Records from the billing section were consequently reviewed upon discharge to account for the professional fees. A data extraction form was used during chart review.

Data were encoded on Microsoft Word format for documentation and analysis was done in Microsoft Excel. Estimated total expenses were itemized as costs of accommodation, diagnostics, treatment, and professional fees as pre-specified. The total computed net expenditure incurred was compared to the actual case rate as follows:

Total net expenditure=Accommodation cost+Diagnostics cost+Therapeutics cost+Professional fess (if applicable)

Out-of-pocket cost=Total net expenditure-Phil-health case rate

Diagnostic and medication expenses for co-morbidities apart from COPD were included as direct costs of the hospitalization. Costing for charity patients under the No Balance Billing system was derived similar to other charity patients, and the same case rate will be implemented. External funding of charity patients from third party financial sources inside PGH were considered as excess costs (hypothetical) for this study based on the formula expressed above. Descriptive statistics was used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. Frequency and proportion were used for categorical variables, median and inter quartile range for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and mean and SD for normally distributed continuous variables. Independent Sample T-test, Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s Exact/Chi- square test were used to determine the difference of mean, rank and frequency, respectively, between charity and private patients. Odds ratio and corresponding 95% confidence intervals from binary logistic regression were computed to determine significant predictors for prolonged hospital stay and hospitalization cost of >P20,000. All statistical tests were two-tailed test. Shapiro-Wilk was used to test the normality of the continuous variables. Missing variables were neither replaced nor estimated. Null hypotheses were rejected at 0.05α-level of significance. STATA 13.1 was used for data analysis.

Names of the research subjects were not indicated in the questionnaires and forms were safely stored in a secure location. The vulnerability of the elderly and socio-economically disadvantaged (charity) patients was considered in the study. The investigators ensured that the best level of care was given and social welfare assistance was provided irrespective of the patient’s decision to participate. This study was performed in accordance with the regulations of the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board and the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. There were no conflicts of interest identified among the investigators.

Results

There were a total of 43 admissions between June 2019 to November 2019 at the Philippine General Hospital with a diagnosis of COPD exacerbation. Table 1 shows the basic demographic characteristics of the patients admitted. All of the patients included in this study had Philippine Health Insurance support, and zero private Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) coverage. The mean age was significantly younger among patients admitted to charity service at 60 years old, while the mean age of patients admitted to private service was at 72 years old. Most of the admissions were predominantly males at 88%, with almost one half residing in a rural environment. Majority of the admissions between the two groups belonged to COPD Class D, and the most common comorbidities reported were hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. The number of pack years was significantly higher among those patients admitted to private service at 47.5 years (mean) as compared to those under charity service at only 22.5 years (mean). The average length of stay was 8 days for both groups. There were no statistical difference between the two groups in terms of sex distribution, type of residence, GOLD classification, comorbidities, smoking history, and length of hospital stay (Table 1).

| Total | Charity | Private | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=43) | (n=28, 65.12%) | (n=15, 34.88%) | ||

| Frequency (%); Mean + SD; Median (IQR) | ||||

| Age | 64.49 + 12.68 | 60.43 + 10.99 | 72.07 + 12.47 | 0.003 |

| 19 to 45 years old | 3 (6.98) | 3 (10.71) | 0 | 0.042 |

| 45 to 64 years old | 20 (46.51) | 16 (57.14) | 4 (28.57) | |

| > 65 years old | 20 (46.51) | 9 (32.14) | 10 (71.43) | |

| Sex | 0.643 | |||

| Male | 38 (88.37) | 24 (85.71) | 14 (93.33) | |

| Female | 5 (11.63) | 4 (14.29) | 1 (6.67) | |

| Type of Residence | 1.000 | |||

| Urban | 23 (53.49) | 15 (53.57) | 8 (53.33) | |

| Rural | 20 (46.51) | 13 (46.43) | 7 (46.67) | |

| Gold Classification | 1.000 | |||

| Class A | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Class B | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Class C | 10 (29.41) | 7 (30.43) | 3 (27.27) | |

| Class D | 24 (70.59) | 16 (69.57) | 8 (72.73) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 20 (46.51) | 10 (35.71) | 10 (66.67) | 0.064 |

| Diabetes | 3 (6.98) | 1 (3.57) | 2 (13.33) | 0.275 |

| Heart disease | 12 (27.91) | 6 (21.43) | 6 (40) | 0.287 |

| Cancer | 2 (4.65) | 2 (7.14) | 0 | 0.535 |

| Number of pack years | 30 (20-50) | 22.5 (20-30) | 47.5 (30-100) | 0.005 |

| Smoking history | 0073 | |||

| Current Smoker | 37 (86.05) | 26 (92.86) | 11 (73.33) | |

| Previous smoker | 3 (6.98) | 0 | 3 (20) | |

| Non-smoker | 3 (6.98) | 2 (7.14) | 1 (6.67) | |

| Length of hospital stay | 8 (6-12) | 8.5 (7-11.5) | 8 (6-31) | 0.759 |

Table 1: Demographic and clinical profile of the patients.

Table 2 shows the type of room accommodation among all COPD exacerbation admissions.

| Room of the patients | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Charity Non-ICU | 22 (51.16) |

| Charity ICU | 6 (13.95) |

| Private Non-ICU | 14 (32.56) |

| Private ICU | 1 (2.33) |

Table 2: Type of room of the patients (n=43).

Majority were admitted to the non-ICU or regular ward rooms, with only 2.33% and 13.95% of these patients requiring ICU level care under charity and private service patients, with respectively.

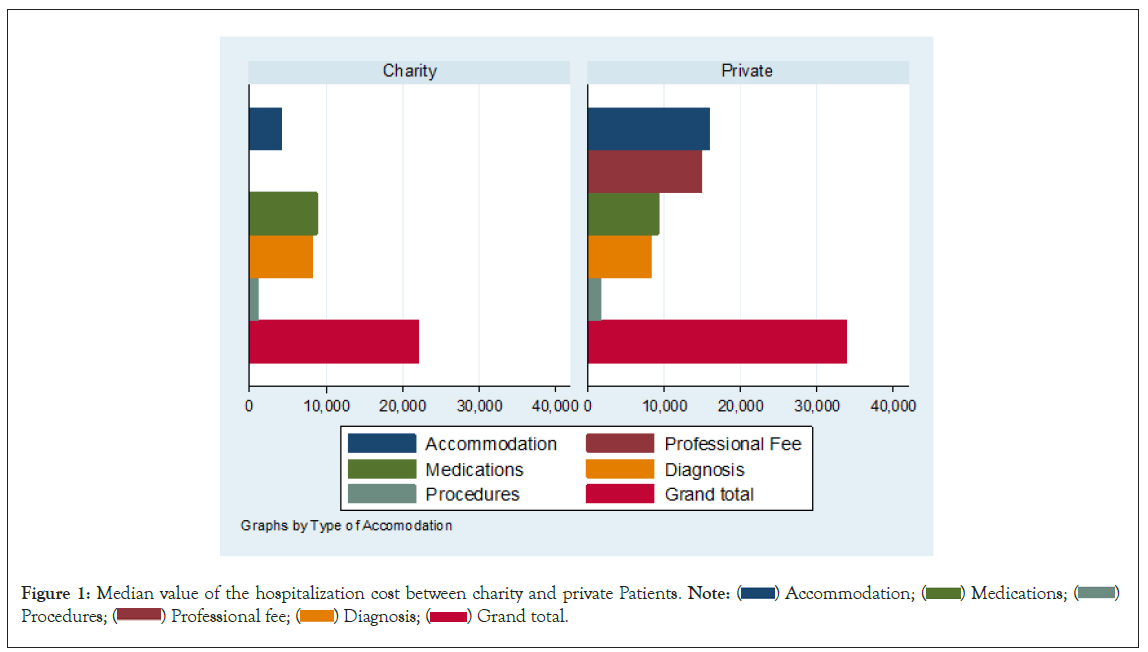

Table 3 shows the hospitalization cost per 1,000 pesos. The average price per day cost of hospital stay is significantly lower for the charity service at 4.25 compared to private service which is almost 4-fold at 16. There were no differences between the two groups in terms of costing for the medications, diagnostic tests, and procedures. The total cost for hospitalization was significantly lower in the charity group compared to the private service patients, with majority of the cost difference likely driven by the absence of professional fees in the former.

| Total (n=43) | Charity (n=28, 65.12%) | Private (n=15, 34.88%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | ||||

| Price per Day | 6 (3.5-13.5) | 4.25 (3.5-5.75) | 16 (8-58.5) | <0.001 |

| Professional fee | 15 (8-17) | - | 15 (8-17) | - |

| Medication cost | 8.96 (6.86-11.71) | 8.83 (6.98-10.42) | 9.33 (6.65-24.56) | 0.575 |

| Diagnostic tests cost | 8.33 (5.76-11.32) | 8.28 (6.53-10.22) | 8.33 (5.2-11.98) | 0.919 |

| Procedural cost | 1.35 (0.32-4.08) | 1.15 (0.31-3.11) | 1.69 (0.57-5.07) | 0.198 |

Table 3: Hospitalization cost (per P1000).

Table 4 shows that age, sex, type of residence, GOLD classification, comorbidities, pack years of smoking, and type of accommodation were not significant predictors of hospital stay of>9 days.

| Prolonged hospital stay | Odds ratio | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=18, 41.86%) | No (n=25,58.14%) | (95% CI) | ||

| Frequency (%); Mean + SD; Median (IQR) | ||||

| Age | 66.39 + 14.81 | 63.12 + 11.04 | 1.02 (0.97-1.07) | 0.402 |

| 19 to 45 years old | 1 (5.56) | 2 (8) | (reference) | - |

| 45 to 64 years old | 8 (44.44) | 12 (48) | 1.33 (0.10-17.3) | 0.826 |

| > 65 years old | 9 (50) | 11 (44) | 1.64 (0.13-21.1) | 0.706 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 14 (77.78) | 24 (96) | (reference) | - |

| Female | 4 (22.22) | 1 (4) | 6.86 (0.70-67.6) | 0.099 |

| Type of Residence | ||||

| Urban | 10 (55.56) | 13 (52) | (reference) | - |

| Rural | 8 (44.44) | 12 (48) | 0.87 (0.26-2.93) | 0.818 |

| Gold Classification | ||||

| Class A | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Class B | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Class C | 4 (40) | 6 (25) | (reference) | - |

| Class D | 6 (60) | 18 (75) | 0.5 (0.10-2.40) | 0.386 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 8 (44.44) | 12 (48) | 0.87 (0.26-2.93) | 0.818 |

| Diabetes | 1 (5.56) | 2 (8) | 0.67 (0.06-8.09) | 0.757 |

| Heart disease | 4 (22.22) | 8 (32) | 0.61 (0.15-2.45) | 0.483 |

| Cancer | 0 | 2 (8) | - | - |

| Number of pack years | 30 (20 to 66) | 30 (20 to 40) | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | 0.255 |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Current Smoker | 12 (66.67) | 25 (100) | (reference) | - |

| Previous smoker | 3 (16.67) | 0 | - | - |

| Non-smoker | 3 (16.67) | 0 | - | - |

| Type of Accommodation | ||||

| Private | 6 (33.33) | 9 (36) | 0.89 (0.25‒3.18) | 0.856 |

| Charity | 12 (66.67) | 16 (64) | (reference) | - |

Table 4: Predictors of prolonged hospital stay.

Table 5 shows that age, sex, type of residence, GOLD classification, comorbidities, pack years of smoking, and type of accommodation were not significant predictors of hospitalization cost of>20,000 pesos.

| Hospitalization cost of > P20,000 | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=33, 76.74%) | No (n=10, 23.26%) | |||

| Frequency (%); Mean + SD; Median (IQR) | ||||

| Age | 63.3 + 13.34 | 68.4 + 9.83 | 0.97 (0.91‒1.03) | 0.267 |

| 19 to 45 years old | 3 (9.09) | 0 | - | - |

| 45 to 64 years old | 15 (45.45) | 5 (50) | 1.0 (0.24‒4.18) | 1 |

| > 65 years old | 15 (45.45) | 5 (50) | (reference) | - |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 28 (84.95) | 10 (100) | (reference) | - |

| Female | 5 (15.15) | 0 | - | - |

| Type of Residence | ||||

| Urban | 18 (54.55) | 5 (50) | (reference) | - |

| Rural | 15 (45.45) | 5 (50) | 0.83 (0.20-3.44) | 0.801 |

| Gold Classification | ||||

| Class A | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Class B | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Class C | 8 (30.77) | 2 (25) | (reference) | - |

| Class D | 18 (69.23) | 6 (75) | 0.75 (0.12-4.56) | 0.755 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 17 (51.52) | 3 (30) | 2.48 (0.54-11.3) | 0.24 |

| Diabetes | 3 (9.09) | 0 | - | - |

| Heart disease | 8 (24.24) | 4 (40) | 0.48 (0.11-2.14) | 0.336 |

| Cancer | 1 (3.03) | 1 (10) | 0.28 (0.02-4.95) | 0.386 |

| Number of pack years | 30 (20-50) | 30 (25-45) | 1.002 (0.98-1.0) | 0.842 |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Current Smoker | 28 (84.85) | 9 (90) | (reference) | - |

| Previous smoker | 2 (6.06) | 1 (10) | 0.64 (0.05-7.95) | 0.731 |

Table 5: Predictors of hospitalization cost of >P20,000.

Figure 1 show the groups admitted under charity service and private service and their breakdown of hospitalization costs itemized under accommodation, medications, procedures, professional fees, diagnosis/diagnostics, procedures, and grand total cost.

Figure 1: Median value of the hospitalization cost between charity and private Patients. Note: ( ) Accommodation; (

) Accommodation; ( ) Medications; (

) Medications; (  )

Procedures; (

)

Procedures; ( ) Professional fee; (

) Professional fee; ( ) Diagnosis; (

) Diagnosis; ( ) Grand total.

) Grand total.

Discussion

This study aimed to prospectively evaluate the overall cost of admissions for COPD exacerbation in a tertiary government hospital over a 6-month period. Despite the existence of Phil-health insurance, the provision of Php 12,200 pesos as the case rate for this diagnosis is inadequate based on this study. With a total mean cost of 22,000 to 51,000 pesos per hospitalization, out-of-pocket expenditure is unavoidable.

A study in the USA on cost of COPD in terms of medical care loss of productivity/absenteeism amounted to $36 billion, with costs projected to even increase for 2020 [20]. As much as 70% of cost of illness is attributed to COPD admissions [21]. A study by Pfuntner, et al. in the USA showed that COPD cost per stay was $6,400 in 1997 which subsequently increased to $7,400 in 2010 with an accounted inflation of 15.6% after 13 years. COPD was among the 3 diagnoses with the highest aggregate cost in the US mainly due to its frequency.

There are variations to costs for different countries. Economic analysis on COPD from different countries reflected varied costs: $522 in France, $1258 in Canada, $3196 in Spain, and $4119 in USA, with the majority of these costs being derived from hospital admissions. Other main sources of direct cost include long term oxygen therapy and maintenance medications after discharge [22].

For our study, mean age was 64.49+12.68, with high prevalence of comorbid conditions. The mean duration of hospital stay was 8 days. There were no significant predictors for cost and duration of stay identified in the present study, and this may be due to the small sample size. According to a study by Torabipour, 2 major drivers for cost for COPD were derived from hospitalizations and medications. Among hospitalized patients, major determinants of costs were history of hypertension, duration of hospital stay, and number of clinical consultations [23]. Therefore, limiting unnecessary clinical consultations, adequate management of comorbidities, and shortening hospitalization stay may potentially equate to lower hospitalization costs for COPD. This study did not measure the following, and therefore represent potential limitations, including indirect costs and productivity losses, discharge medication costs and procedures (rehabilitation, long-term oxygen therapy).

Conclusion

Our study indicated that the mean hospitalization cost for COPD exacerbation is 28,200 with significantly lower cost for charity admissions at 22,870 Philippine pesos (mean) versus private admissions at 51,320 pesos (mean) in the Philippines. Despite the existence of Phil-health, in-patient coverage for this disease was still insufficient. Majority of the patients were in the elderly age group, with a high prevalence of comorbidities. The present study was not able to identify major drivers for cost or prolonged hospitalization stay. However, measures such as maximizing COPD control in the out-patient setting, avoiding unnecessary tests procedures, reducing hospital stay could potentially reduce total cost for this disease. Similar studies that will employ a larger sample size include indirect costs, and recruit patients from different institutions to account for variations in health care delivery systems and financial sources are recommended.

Declarations

Availability of data and materials

The datasets may be accessed from the authors, with proper permission from the authors and institution. Dr. Blake Warren Ang may be contacted for the dataset of this study through blakewarrenmd@yahoo.com

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of the Philippines- Manila Research Ethics Board and all the methodologic steps were in accordance with the ethical regulations of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

Consent to Publication

Not applicable

Competing Interests

There were no competing interests of a financial or personal nature for the authors. No funding was given for this study

Author's Contributions

The contributions of Dr. Blake Warren Ang and Dr. Lenora Fernandez were equal for all parts of the study and manuscript preparation.

Funding

No funding from any source was given for this study.

References

- Burden of COPD. World Health Organization.

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2163–2196.

[PubMed]

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095-2128.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- López‐Campos JL, Tan W, Soriano JB. Global burden of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(1):14-23.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ang BW, Fernandez L. A Prospective Study on Direct Out-of-Pocket Expenses of Hospitalized Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in a Philippine tertiary care center.

- Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gillespie S, Burney P. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): A population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):741-750.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim S, Lam DC, Muttalif AR, Yunus F, Wongtim S, Lan LT, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the Asia-Pacific region: The EPIC Asia population-based survey. Asia Pac Fam Med 2015;14(1):1-1.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A training manual for health workers on healthy life style: An approach for the prevention and control of Noncommunicable diseases. 2009.

- De Oca MM, Pérez-Padilla R. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD)-2017: The ALAT perspective. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(3):87-88.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soriano JB, Miravitlles M, Borderías L, Duran-Tauleria E. Geographical variations in the prevalence of COPD in Spain: Relationship to smoking, death rates and other determining factors. Arch Bronconeumol. 2010;46(10):522-530.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones R, Dickson-Spillmann M, Mather MJ, Marks D, Shackell BS. Accuracy of diagnostic registers and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The Devon primary care audit. Respir Res. 2008;9(1):1-9.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miravitlles M, Guerrero T, Mayordomo C, Sánchez-Agudo L, Nicolau F, Segú JL. Factors associated with increased risk of exacerbation and hospital admission in a cohort of ambulatory COPD patients: A multiple logistic regression analysis. Respiration. 2000;67(5):495-501.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torabipour A, Hakim A, Angali KA, Dolatshah M, Yusofzadeh M. Cost analysis of hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A state-level cross-sectional study. Tanaffos. 2016;15(2):75.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anzueto A, Sethi S, Martinez FJ. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(7):554-564.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim C, Yoo KH, Rhee CK, Yoon HK, Kim YS, Lee SW, et al. Health care use and economic burden of patients with diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(6):737-743.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung K, Kim K, Jung J, Oh K, Oh Y, Kim S, et al. Patterns and determinants of COPD-related healthcare utilization by severity of airway obstruction in Korea. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14(1):1-0.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beran D, Zar HJ, Perrin C, Menezes AM, Burney P. Burden of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and access to essential medicines in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(2):159-170.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ang BW, Fernandez L. A Prospective Study on Direct Out-of-Pocket Expenses of Hospitalized Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in a Philippine tertiary care center. 2023.

- Philhealth. History. Retrieved from.

- Lung Center of the Philippines. Most Common Medical Case Rates. 2018.

- Ford ES, Murphy LB, Khavjou O, Giles WH, Holt JB, Croft JB. Total and state-specific medical and absenteeism costs of COPD among adults aged 18 years in the United States for 2010 and projections through 2020. Chest. 2015;147(1):31-45.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Stavem K, Dahl FA, Humerfelt S, Haugen T. Factors associated with a prolonged length of stay after acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014:99-105.

[Google Scholar] [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Steiner C. Costs for hospital stays in the United States. 2010.

Citation: Lenora F, Warren AB (2023) A Prospective Study on Direct Out-Of-Pocket Expenses of Hospitalized Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in a Philippine Tertiary Care Center. J Clin Res Bioeth.14:458.

Copyright: © 2023 Lenora F, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.