Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

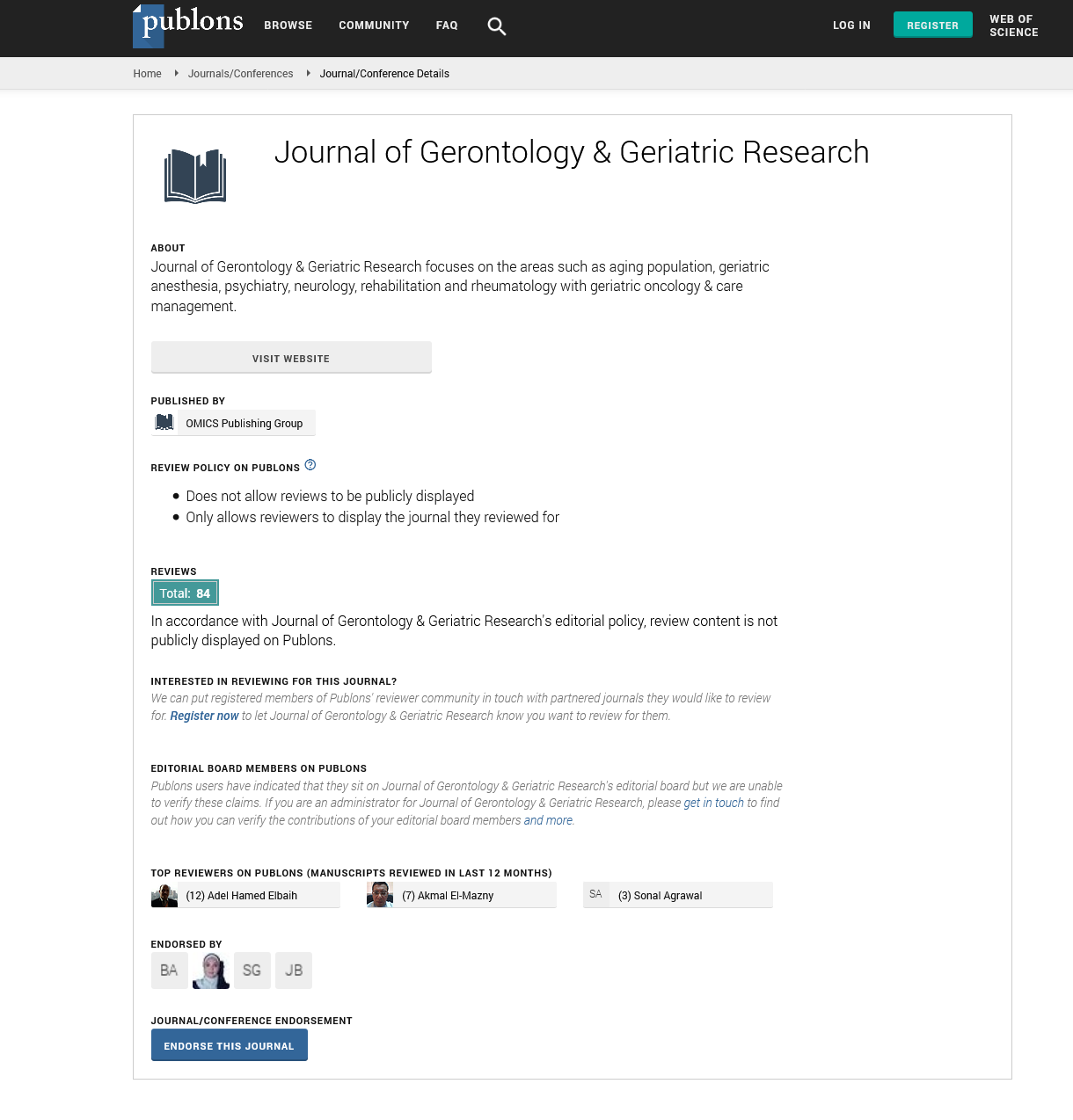

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Commentary Article - (2023) Volume 12, Issue 1

A Colonial Chordate's Cyclical Brain Degeneration is accompanied by multiple forms of Neural Cell Death

Lucia Manni*Received: 02-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. jggr-23-20889; Editor assigned: 05-Jan-2023, Pre QC No. P-20889; Reviewed: 17-Jan-2023, QC No. Q-20889; Revised: 23-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. R-20889; Published: 30-Jan-2023, DOI: 10.35248/2167-7182.2023.12.654

Description

Due to the anatomical complexity of animals, studies of neuronal cell death are currently mostly conducted in vitro using mammalian cell lines. Solid and basic creature models are extremely helpful to in vivo examinations on neuronal cell demise and its job in the life form in general. Tunicates are marine invertebrates, which are regarded as members of the vertebrate sister order More specifically, the marine colonial tunicate Botryllus schlosseri, which shares a high degree of genomic homology with mammals has the potential to shed light on the development of neuronal cell death mechanisms that are associated with aging and neurodegenerative diseases Tunicates, as translational models, are of key significance for two principal reasons: when pharmacological interventions may still be effective, they provide an to study the entire process of neurodegeneration, including those relevant to the pre-clinical stages of human neurodegenerative disorders; They provide a novel, combined model of cyclical degeneration and neural development in colonial species, revealing potential neural protection mechanisms in growing buds [1,2].

Tunicates exhibit apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy throughout their lives which also includes a mobile larval stage. It possesses most of the chordate characteristics that tunicates and vertebrates share: a notochord in the tail, a ventral endoderm, bilateral striated muscles, and a dorsal neural tube that produces a tripartite brain These characteristics are lost during transformation, an interaction during which the tail is totally resorbed through apoptosis plays a role in the cyclical events of adult resorption in the colonial tunicate, which take place in a phase known as takeover In this species, three determined ages of zooids coincide in a state: the grown-up, channel taking care of people, their buds and an age of little buds generational shift occurs weekly at the grown-up people kick the bucket at the same time and are resorbed by the province.

Primary buds begin filtration by opening their siphons and becoming the new generation of adult zooids; and new generations of are produced as the secondary buds transform into primary buds. Apoptosis is necessary for bud development and only occurs in the adult generation during the takeover, which lasts less than 48 hours is a suitable candidate for weekly, without the need for experimental induction, study of various pathways of cell death at the organism level due to its recurrent and massive natural degeneration. In contrast, the mode of cell death that takes place during the senescence of colonies is necrosis The latter stage, which involves all asexually derived generations of aged colonies, lasts about a week and proceeds according to a series of characteristic changes like vascular constriction and congestion, massive pigment cell accumulation in several districts, gradual zooid shrinkage, loss of colony architecture, and death It is important to note that, despite the fact that both the takeover and the senescence are processes with a limited amount of time, they are both prepared by progressive degenerative events that are particularly evident in the nervous system [3-5].

We found a progressive accumulation of small vesicles neurites that were both elongated and closely resembled the tubulovesicular structures that are thought to be the ultrastructural hallmark of prion diseases Although larger vesicular profiles measuring nm in diameter have been reported, which would be comparable to those we found in B. schlosseri, the tubulovesicular structures previously described are spheres or short rods with a diameter of at terminal takeover, these small vesicles were found not only in neurites but also in neural gland cells, indicating the progressive degenerative involvement of contiguous structures as in prion-like diseases over the course of many neurodegenerative disorders in human and animal models a progressive medulla vacuolization resembling the typical prion disease vacuolization with a spongiform neuropil morphological and transcriptomic evidence of multiple neuronal cell death modes associated with the aforementioned conformational disorders; qualities related with prion infections that are exceptionally communicated not long before the takeover beginning, when the brain misfortune has recently started. As a result, we conclude that protein aggregates can lead to neuronal dysfunction and death, possibly through a prion-like cell-to-cell propagation, as suggested by gene heatmaps and morphological findings.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Schauvliege S. Drugs for cardiovascular support in anesthetized horses. Vet Clin Equine Pract. 2013; 29:19-49.

- De Vries A. Effects of dobutamine on cardiac index and arterial blood pressure in isoflurane‐anaesthetized horses under clinical conditions. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2009; 32:353-8.

- Goldman RH. Measurement of central venous oxygen saturation in patients with myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1968; 38:941-6.

- Okorie ON. Biomarker and potential therapeutic target. Critical care clinics. 2011; 27:299-326.

- Raisis AL. Skeletal muscle blood flow in anaesthetized horses. Effects of Anaesthetics and Vasoactive Agents. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2005; 32:331-7.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Citation: Manni L (2023) A Colonial Chordate’s Cyclical Brain Degeneration is accompanied by multiple forms of Neural Cell Death. J Gerontol Geriatr Res.12: 654.

Copyright: © 2023 Manni L. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.