Indexed In

- JournalTOCs

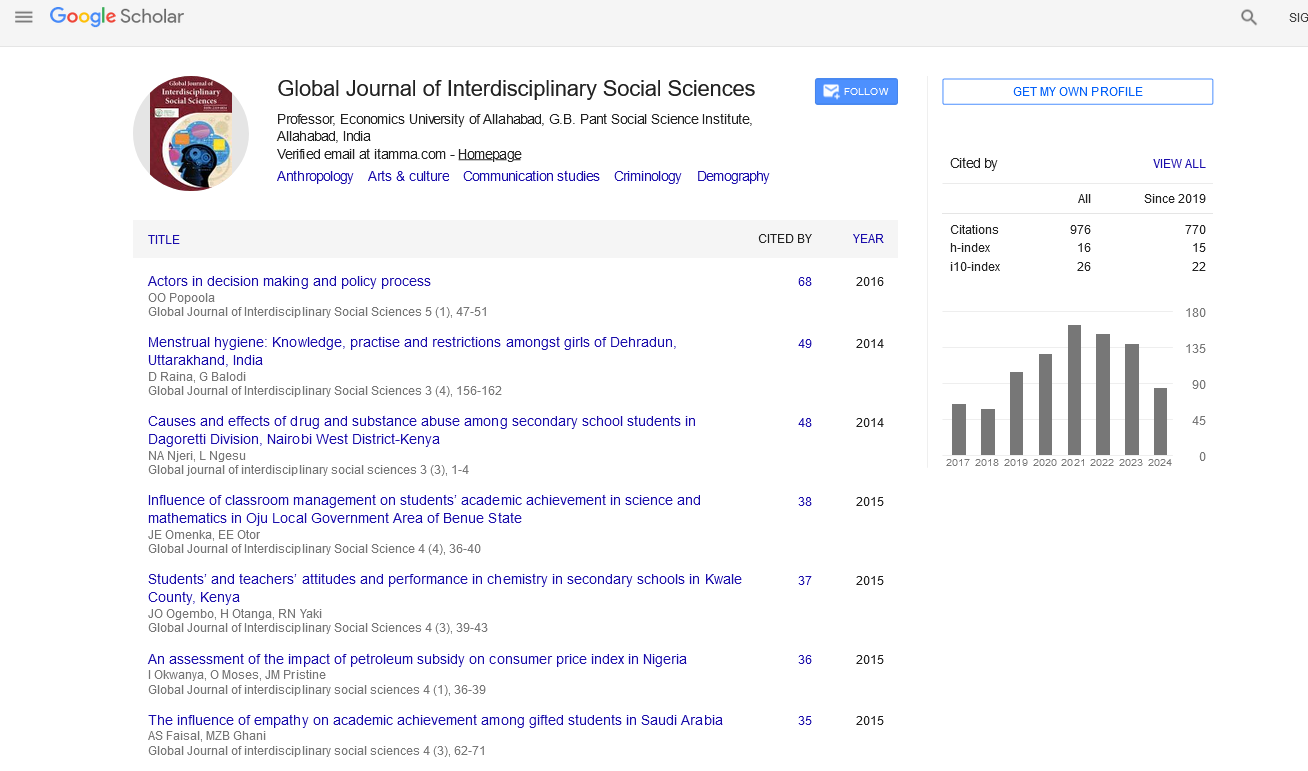

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Abstract

Journalism

Rachel Z Allen

News-casting in the twentieth century was set apart by a developing feeling of polished skill. There were four significant factors in this pattern: (1) the expanding association of working writers, (2) particular instruction for news-casting, (3) a developing writing managing the set of experiences, issues, and methods of mass correspondence, and (4) an expanding feeling of social duty with respect to columnists. An association of writers started as ahead of schedule as 1883, with the establishment of England's contracted Institute of Journalists. Like the American Newspaper Guild, coordinated in 1933, and the Fédération Nationale de la Presse Française, the establishment worked as both a worker's organization and an expert association.

Prior to the last piece of the nineteenth century, most columnists took in their art as understudies, starting as copyboys or fledgling journalists. The main college course in news coverage was given at the University of Missouri (Columbia) in 1879–84. In 1912 Columbia University in New York City set up the principal graduate program in news-casting, blessed by an award from the New York City manager and distributer Joseph Pulitzer. It was perceived that the developing intricacy of information revealing and paper activity required a lot of particular preparing. Editors likewise tracked down that inside and out detailing of unique sorts of information, like political undertakings, business, financial matters, and science, frequently requested journalists with schooling around there. The appearance of movies, radio, and TV as news media required a consistently expanding battery of new abilities and procedures in social affair and introducing the news. By the 1950s, courses in news coverage or correspondences were usually offered in schools.

The writing of the subject—which in 1900 was restricted to two course books, a couple of assortments of talks and articles, and few narratives and life stories—got extensive and changed by the late twentieth century. It went from narratives of news coverage to messages for correspondents and picture takers and books of conviction and discussion by writers on editorial abilities, strategies, and morals. Worry for social duty in news-casting was to a great extent a result of the late nineteenth and twentieth hundreds of years. The most punctual papers and diaries were by and large savagely sectarian in governmental issues and thought about that the satisfaction of their social duty lay in converting their own gathering's position and upbraiding that of the resistance. As the perusing public developed, be that as it may, the papers filled in size and riches and turned out to be progressively free. Papers started to mount their own famous and shocking "campaigns" to build their dissemination. The zenith of this pattern was the opposition between two New York City papers, the World and the Journal, during the 1890s (see sensationalist reporting).

The feeling of social obligation made prominent development because of specific training and far and wide conversation of press duties in books and periodicals and at the gatherings of the affiliations. Such reports as that of the Royal Commission on the Press (1949) in Great Britain and the less broad A Free and Responsible Press (1947) by an informal Commission on the Freedom of the Press in the United States did a lot to animate self-assessment with respect to rehearsing writers.

By the late twentieth century, contemplates showed that writers as a gathering were by and large hopeful about their part in acquiring current realities to the public a fair-minded way. Different social orders of columnists gave proclamations of morals, of which that of the American Society of Newspaper Editors is maybe most popular. Albeit the center of news-casting has consistently been the information, the last word has procured such countless auxiliary implications that the expression "hard news" acquired money to recognize things of unmistakable news esteem from others of minor importance. This was generally an outcome of the approach of radio and TV revealing, which carried news notices to general society with a speed that the press couldn't expect to coordinate. To hold their crowd, papers gave expanding amounts of interpretive material—articles on the foundation of the news, character portrayals, and sections of convenient remark by authors talented in introducing assessment in decipherable structure. By the mid-1960s most papers, especially evening and Sunday releases, were depending intensely on magazine strategies, with the exception of their substance of "hard news," where the conventional principle of objectivity actually applied. Newsmagazines in quite a bit of their revealing were mixing news with article remark. News-casting in book structure has a short however distinctive history. The expansion of soft cover books during the a very long time after World War II offered catalyst to the editorial book, exemplified by works detailing and breaking down political races, political embarrassments, and world issues all in all, and the "new news-casting" of such writers as Truman Capote, Tom Wolfe, and Norman Mailer.

Published Date: 2021-05-28;